Introduction

Would you like to be notified when a new survey report is released? Sign up here

Talking politics with family or partners can be a recipe for conflict. However, completely avoiding these topics in our romantic and familial relationships is somewhat difficult. Politics and political ideas reflect our core values. Therefore, having discussions about these can be a useful way to share, discuss and discover how we differ from our nearest and dearest.

Our political ideas often come from our parents. Political socialisation studies have found a strong correlation between parents’ and children’s political ideations, suggesting a generational transfer of political ideas (Hyman, 1959; Greenstein, 1965; Hess & Torney, 1967).

Romantically, many people seek a partner who aligns politically with them. Alford and associates found that a couple’s political affinity is one of the strongest of all social and biometric traits (2011). Findings suggest that this similarity is usually part of what draws couples together, rather than appearing through accommodations by the couple over time (Alford et al. 2011). However, this is contested and difficult to test for, as studying couples before they have met is challenging. Online dating has provided an antidote to this conundrum. Anderson and colleagues found that online, individuals evaluate potential partners more favourably and are more likely to reach out to them if they have similar political leanings (2017).

While some feel that ‘love is enough’, navigating a relationship with discordant political values can be challenging. The relationships indicators survey conducted by Relationships Australia found that ‘different expectations/values’ is a leading cause of relationship breakdowns in Australia (2011). In response, families and couples sometimes avoid talking about politics altogether. Strategic topic avoidance is a strategy used to maintain emotional closeness while avoiding potentially divisive discussions (Dailey & Palomares, 2004). However, learning to talk about politics in a respectful and open-minded way can be part of the process of socialisation and a way to learn democratic skills (Levinsen & Yndigegn, 2015). Similarly, political discussions between generations leads to greater civility (Bloemraad & Trost, 2008).

The June 2019 survey sought to explore individuals’ attitudes towards bipartisan relationships, how their politics align with their partner’s and family, and strategies for having political discussions with their families.

Previous research finds that…

- The best predictor of an individual’s party preference is the preference of their parents (Knoke 1972).

- While it is well noted that couples often align politically (Martin et al. 1986; Alford et al. 2011), it is unknown whether this is reflective of a choice or a side-effect of other factors that are correlated with shared political orientations (Anderson 2017).

- Women’s relationship satisfaction is closely linked to a similarity in political attitudes with their partners (Leikas et al. 2018)

- Similarity in attitudes enables understanding and therefore assists couples who are experiencing relationship-related distress (Gonzaga et al. 2007)

Results

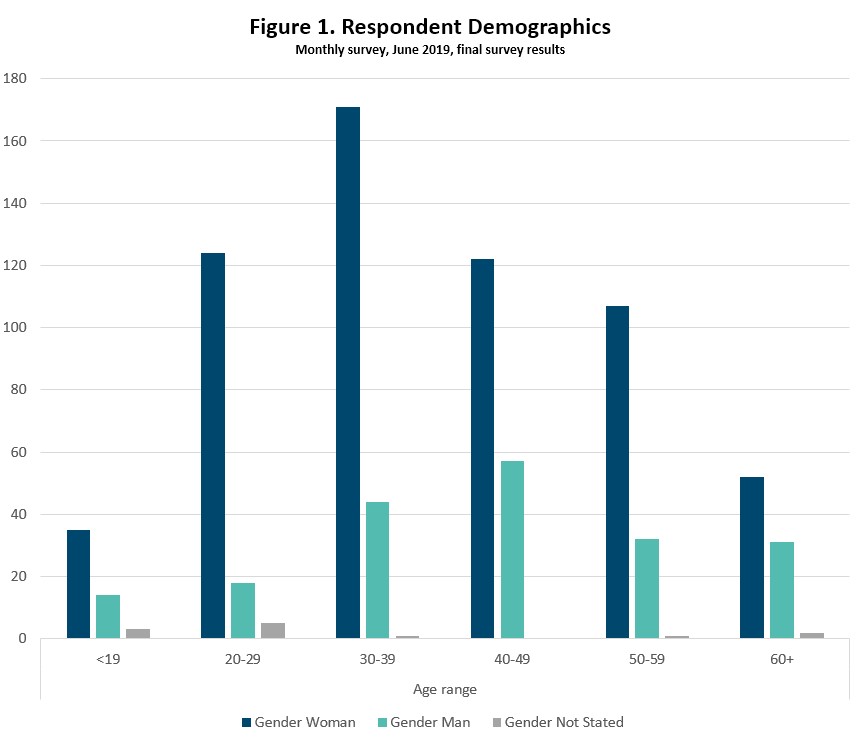

865 people responded to the Relationships Australia June 2019 survey. Seventy-two percent of respondents were female, a majority (27%) of those were aged between 30-39, with another forty percent of women aged between 20-29 and 40-49 (Figure 1). Fifty-one percent of men were aged between 30-49 (Figure 1).

As for previous surveys, the demographic profile of survey respondents is consistent with our experience of the groups of people that would be accessing the Relationships Australia website.

Partners and Politics

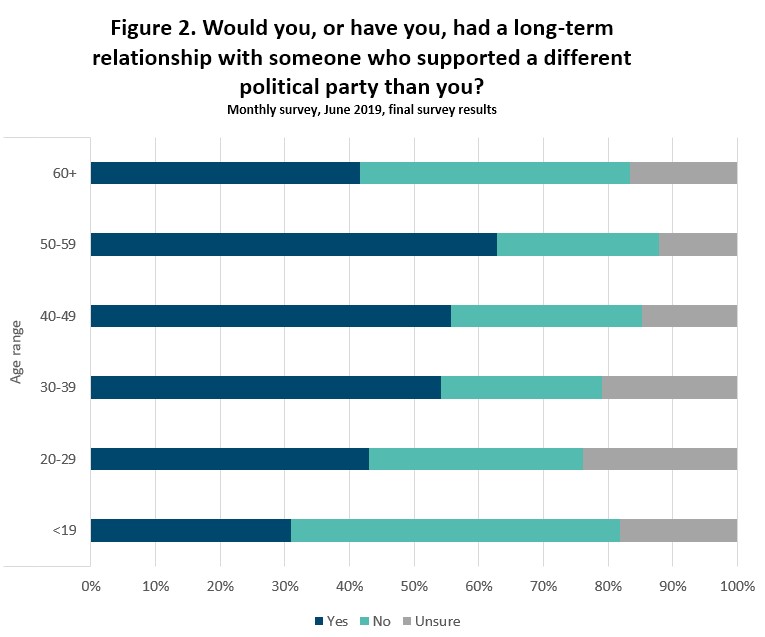

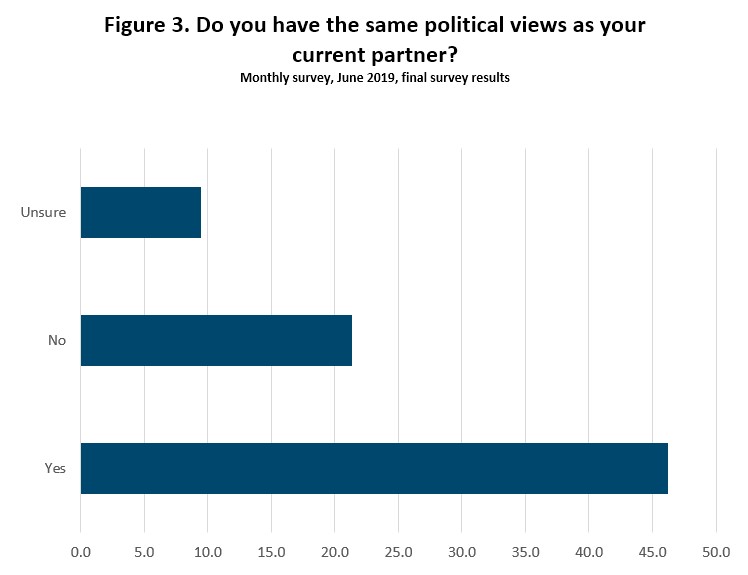

Over half (52%) of respondents said they would, or have had, a long-term relationship with someone who supported a different political party than them. People aged below 19 and above 60 were less willing to cross political lines in their romantic relationships (Figure 2). However, despite an overall willingness to date cross-politically, forty-six percent of respondents were in a relationship with someone with the same political views (Figure 3).

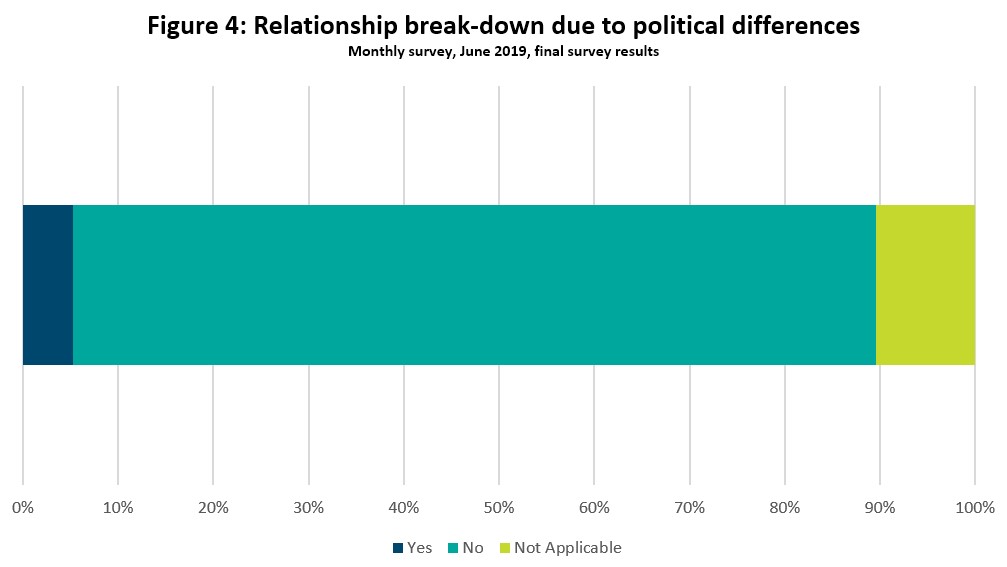

Further, only five percent of respondents said they had experienced a relationship break‑down due to political differences (Figure 4). This suggests the willingness of respondents to enter into relationships with political counterparts (illustrated in Figure 2) is either theoretical (they are willing to but have not done so) or, if the relationship has broken down, it has done so for reasons other than politics.

Family and Politics

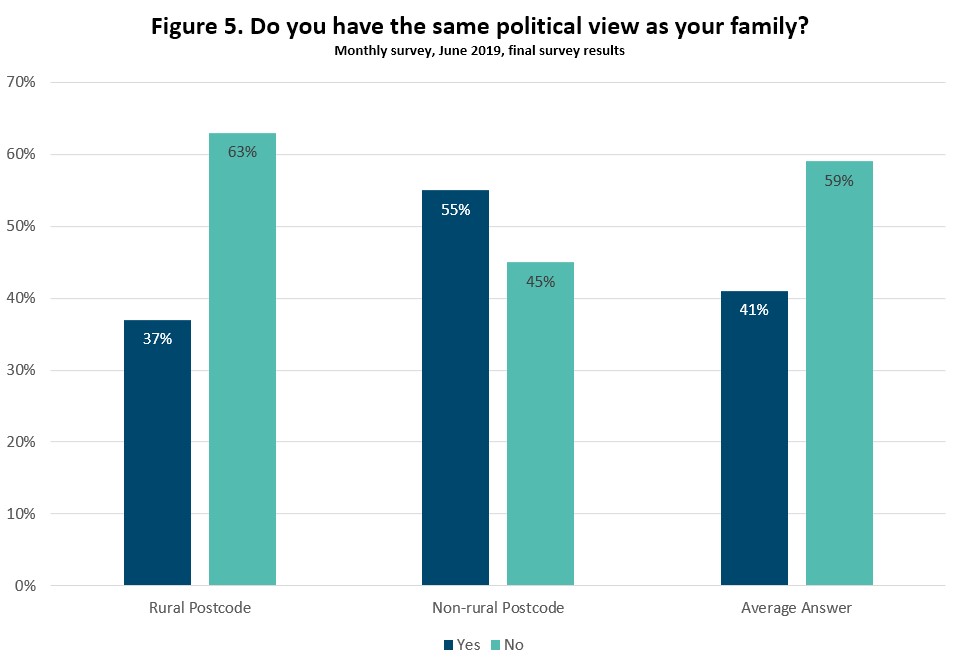

Overall, fifty-nine percent of respondents said they did not share their family’s political views (Figure 5 – these statistics did not include answers ‘unknown’ or ‘not applicable’). However, of those who provided a rural postcode, it was even less common to share their family’s political views (63% did not) [rural postcodes defined with reference to the Department of Health 2018 list]. Contrastingly, those with non-rural postcodes were more likely to share their family’s political views (55% did). This suggests that differences in political affiliations among family members is more prominent in rural locations.

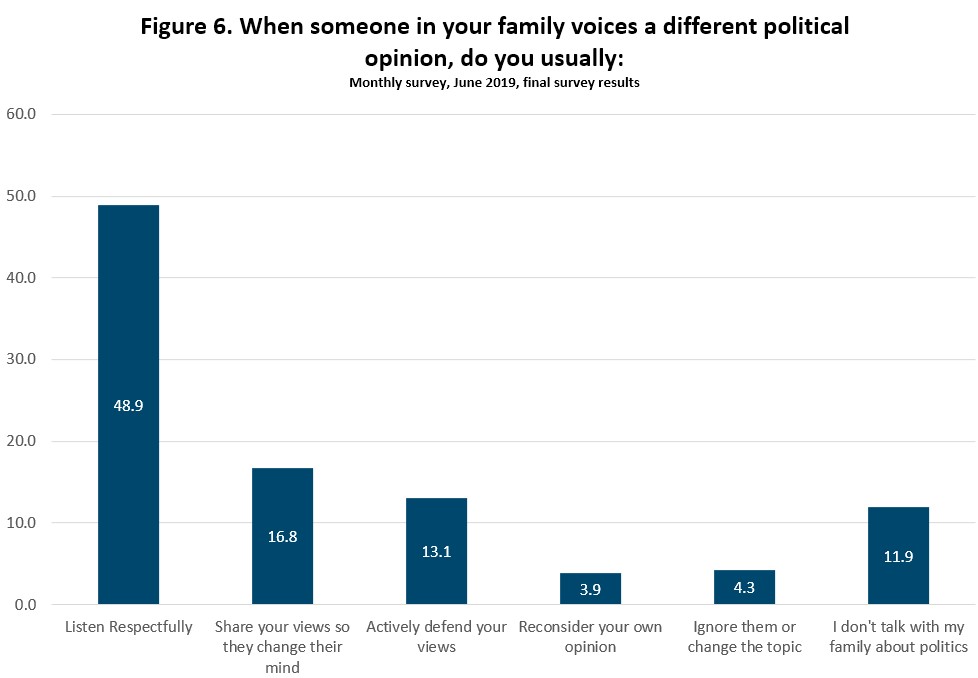

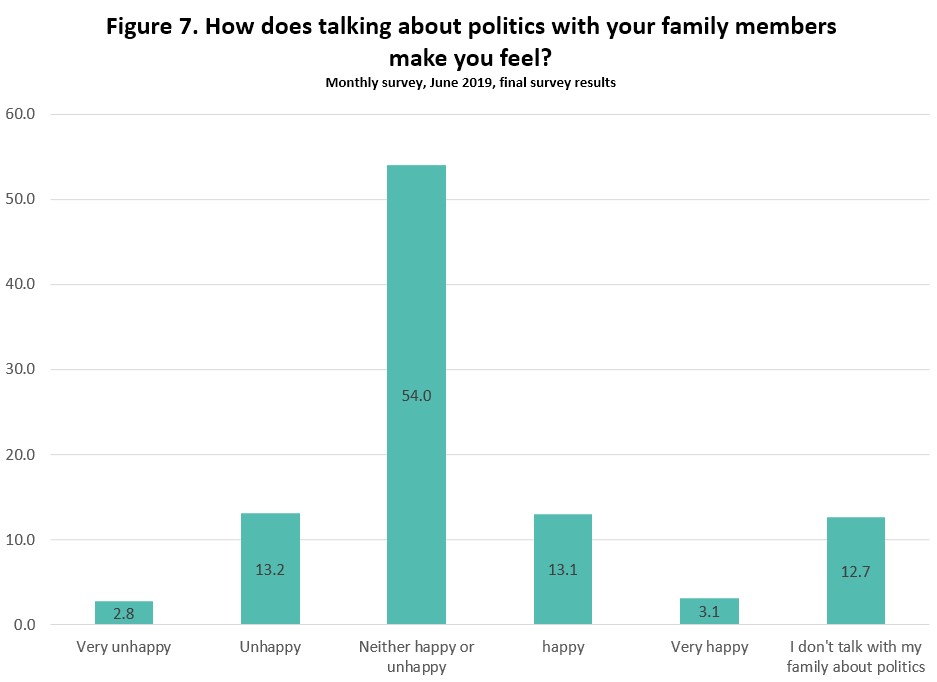

When discussing politics, fifty-three percent of respondents suggested that they would adopt a neutral/positive response, stating that they would either listen respectfully (49%) or reconsider their own opinion (4%) (Figure 6). Despite this, only nineteen percent of these respondents felt positively (happy or very happy) when speaking about politics with their families (Figure 7). This suggests that politics remains a somewhat uncomfortable topic, despite widespread understanding that openness to others’ opinions is appropriate.

References

Alford, J., Hatemi, P., Hibbing, J., Martin, N., & Eaves, L. (2011). The Politics of Mate Choice. The Journal Of Politics, 73(2), 362-379.

Anderson, A., Goel, S., Huber, G., Malhotra, N., & Watts, D. (2014). Political Ideology and Racial Preferences in Online Dating. Sociological Science, 1(1), 28-40.

Bloemraad, I., & Trost, C. (2008). It’s a Family Affair: Intergenerational Mobilization in the Spring 2006 Protests. American Behavioral Scientist, 52(4), 507-532.

Dailey, R., & Palomares, N. (2004). Strategic topic avoidance: an investigation of topic avoidance frequency, strategies used, and relational correlates. Communication Monographs, 71(4), 471-496.

Gonzaga, G., Campos, B., & Bradbury, T. (2007). Similarity, convergence, and relationship satisfaction in dating and married couples. Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology, 93(1), 34-48.

Greenstein, F. (1969). Children and Politics. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Hyman, H. (1969). Political socialization. New York: Free Press.

Knoke, D. (1972). A Causal Model for the Political Party Preferences of American Men. American Sociological Review, 37(6), 679.

Leikas, S., Ilmarinen, V., Verkasalo, M., Vartiainen, H., & Lönnqvist, J. (2018). Relationship satisfaction and similarity of personality traits, personal values, and attitudes. Personality And Individual Differences, 123, 191-198.

Levinsen, K., & Yndigegn, C. (2015). Political Discussions with Family and Friends: Exploring the Impact of Political Distance. The Sociological Review, 63(2), 72-91.

Martin, N., Eaves, L., Heath, A., Jardine, R., Feingold, L., & Eysenck, H. (1986). Transmission of social attitudes. Proceedings Of The National Academy Of Sciences, 83(12), 4364-4368.

R. D. Hess and J. V. Torney, The Development of Political Attitudes in Children. Chicago: Aldine Press, 1967, pp. 288.

Relationships Australia. (2011). Relationships Indicators Survey (p. 11). Retrieved from https://www.relationships.org.au/what-we-do/research/australian-relationships-indicators/relationships-indicator-2011