Relationship Indicators 2022 Report

Introduction

The Relationship Indicators project is a nationally representative survey into the state of relationships in Australia. Relationships are a major part of the human experience. From the moment we are born, we are in relationships with ourselves and others. Relationships can be a source of love, joy, intimacy, connection and belonging. Relationships can also cause anxiety, frustration, disappointment, grief, fear, and pain. Important and meaningful connections build us up. When our relationships are strong, we can overcome incredible challenges. Equally, relationship breakdown and loss can tear us apart. The re-launch of the Relationship Indicators survey attempts to capture these nuances and help us understand the importance of relationships across the life course.

The new survey

Relationships Australia has sought to develop a national survey which explored the ‘most important, meaningful’ relationship people have in their lives. Traditionally, many may assume that a person’s partner would take on this role. And for many of our participants, this was the case. However, we also felt it was important to capture the incredible connection people have outside of partnered relationships and explore the difficulties and challenges these relationships face. The survey also explores people’s experiences with partnered relationship breakdown and bereavement, as well as other emerging relationship issues. Finally, we focused on people’s social identities, by exploring the roles that group relationships play in our lives.

To design the survey, we used a panel of experts from across our Federation and beyond. This resulted in a survey with a variety of rigorous measures, validated tools and some questions to test our own assumptions as service providers. Our approach produced findings which are broadly applicable to the Australian population. Despite this, we recognise that distilling relationships, which are so personal and infinitely subjective, into a short, summative report is a difficult task. As such, we plan to use this research as a launching point for more in-depth work. For now, we hope the findings of this research can start a larger conversation about the integral role relationships play across the lifespan, and the kinds of supports that all Australians need to achieve respectful, enduring relationships.

Support resources

If you need support in relation to the issues mentioned throughout this report, please find a list of useful resources here.

Demographics

Demographics

Your Subtitle Goes Here

Relationship Indicators findings are considered representative of the Australian adult population. The Relationship Indicators survey had 3140 respondents; this sample was benchmarked to reflect the gender, age, and locations of the Australian population.1 The survey was then weighted to correct any imbalances between the survey sample and the Australian population or any biases in sample selection. For more information on the approach to weighting, please see the Technical Report.

To access a full demographic breakdown of the sample please see the Dashboard.

Key terms

Key terms

Your Subtitle Goes Here

Australians – Relationships Australia provides services to all members of the Australian community, regardless of religious belief, age, gender, sexual orientation, lifestyle choice, cultural background or economic circumstances. Throughout our analysis we use the term Australian to refer to anyone living in Australia over the age of 18.

Carers – people who provide unpaid care and support to family members and friends who have a disability, mental illness, chronic condition, terminal illness, an alcohol or other drug issue or who are elderly.

Dissatisfied – refers to those who agreed with the negative semantics in the relationship satisfaction scale. For example, they felt their relationship was bad, therefore they are dissatisfied.

Life in Australia™ – The Social Research Centre’s panel used to collect the data for this report.

Most important relationship – In the first section of the survey, we asked people to think of the three people closest to them and from this, select their most important, meaningful relationship. We then asked people a series of questions exploring this relationship. Throughout the survey, we refer to this as the as their ‘most important relationship’ or ‘most important person’.

Open-relationship – Being in a relationship with multiple partners at once. This is sometimes known as a polyamorous relationship, consensual non-monogamous relationship or ethical non-monogamous relationship. It is different from infidelity because everyone is aware and consents.

Partner – throughout this report we use the word partner to refer to a sexual, romantic or intimate relationship. Other terms for this could include boyfriend, girlfriend, spouse, de facto, intimate partner, husband, wife.

Partnered relationships – refers to the relationship between two people that could be sexual, romantic or intimate. Used instead of the more gendered terms such as boyfriend, girlfriend, spouse, de facto, intimate partner, husband, wife.

Relationship dissatisfaction – refers to those who agreed with the negative semantics in the relationship satisfaction scale. For example, they felt their relationship was bad, therefore they are dissatisfied.

Relationship dysfunction – a term used by researchers to describe turbulance within the relationship. If dysfunction is present, relationship satisfcation may be reduced.

Relationship Indicators – National survey conducted by Relationships Australia to explore the experience of relationships in Australia.

RIAG – Relationship Indicators Advisory Group which included experts from across the Relationships Australia Federation.

Unsatisfied – refers to those who did not fully agree with the positive semantic measures of a satisfied relationship. For example, they didn’t feel their most important relationship was completely friendly, and therefore their relationship is missing an element, but it does not necessarily equate to a dissatisfying relationship.

Data Collection and question design

Data Collection and question design

Your Subtitle Goes Here

Authors

Authors

Your Subtitle Goes Here

Data Analyst – Lei Huang, Relationships Australia National

Data support – Dr Glenn Althor, Relationships Australia New South Wales

The Relationship Indicators Advisory Group

Dr Glenn Althor, Relationships Australia New South Wales; Dr Shannon Harvey, Relationships Australia New South Wales; Dr Heather Pearce, Relationships Australia South Australia; Dr Jemima Petch, Relationships Australia Queensland; Dr Michael Kelly, Relationships Australia Tasmania; Charmaine Don and Donna Quinn, Relationships Australia Western Australia; Dr Genevieve Heard, Relationships Australia Victoria; Michael Meegan, Relationships Australia Northern Territory; Dr Susan Cochrane and Nick Tebbey Relationships Australia National

Loneliness advisor

Dr Roger Patulny, University of Wollongong.

The Relationships Australia CEO committee (from November 2021- February 2022)

Dr Michael Kelly, Relationships Australia Tasmania, Alison Brook, Relationships Australia Canberra and Region, Dr Andrew Bickerdike, Relationships Australia Victoria, Dr Claire Ralfs, Relationships Australia South Australia, Dr Elisabeth Shaw, Relationships Australia New South Wales, Dr Ian Law, Relationships Australia Queensland, Michael Meegan, Relationships Australia Northern Territory and Terri Reilly, Relationships Australia Western Australia

Life in Australia™ Social Research Centre

Anna Lethborg Research Director; Lauren Spencer Senior Research Consultant; Dale VanderGert Project Manager; Blair Johnston Project Manager

Cognitive Interviewing

Relationships Australia New South Wales User Expert Panel

Relationship Indicators Key Findings

- Australians2 have a variety of important, meaningful connections. Australians are very satisfied with these relationships.

- Satisfying relationships lead to greater subjective wellbeing and can predict satisfaction with life more generally.

- External pressures are placing a significant strain on relationships, affecting some groups more than others.

- Loneliness is increasing in Australia. More people say they often feel lonely and levels of social loneliness3 are high across the whole population.

- Too many feel unsafe disagreeing with their most important person, with older Australians least likely to say they feel safety in their relationships.

- Experiences with grief and loss in a partner relationship have significant ongoing effects on future relationships.

- Men are struggling to connect emotionally and socially and create strong relationships.

- Having a strong and reliable relationship improves subjective wellbeing, reduces loneliness, and enhances mental health.

- Australians have very low rates of help-seeking to address relationship issues, preferring to manage these challenges on their own.

The significance of important, meaningful relationships

Key points

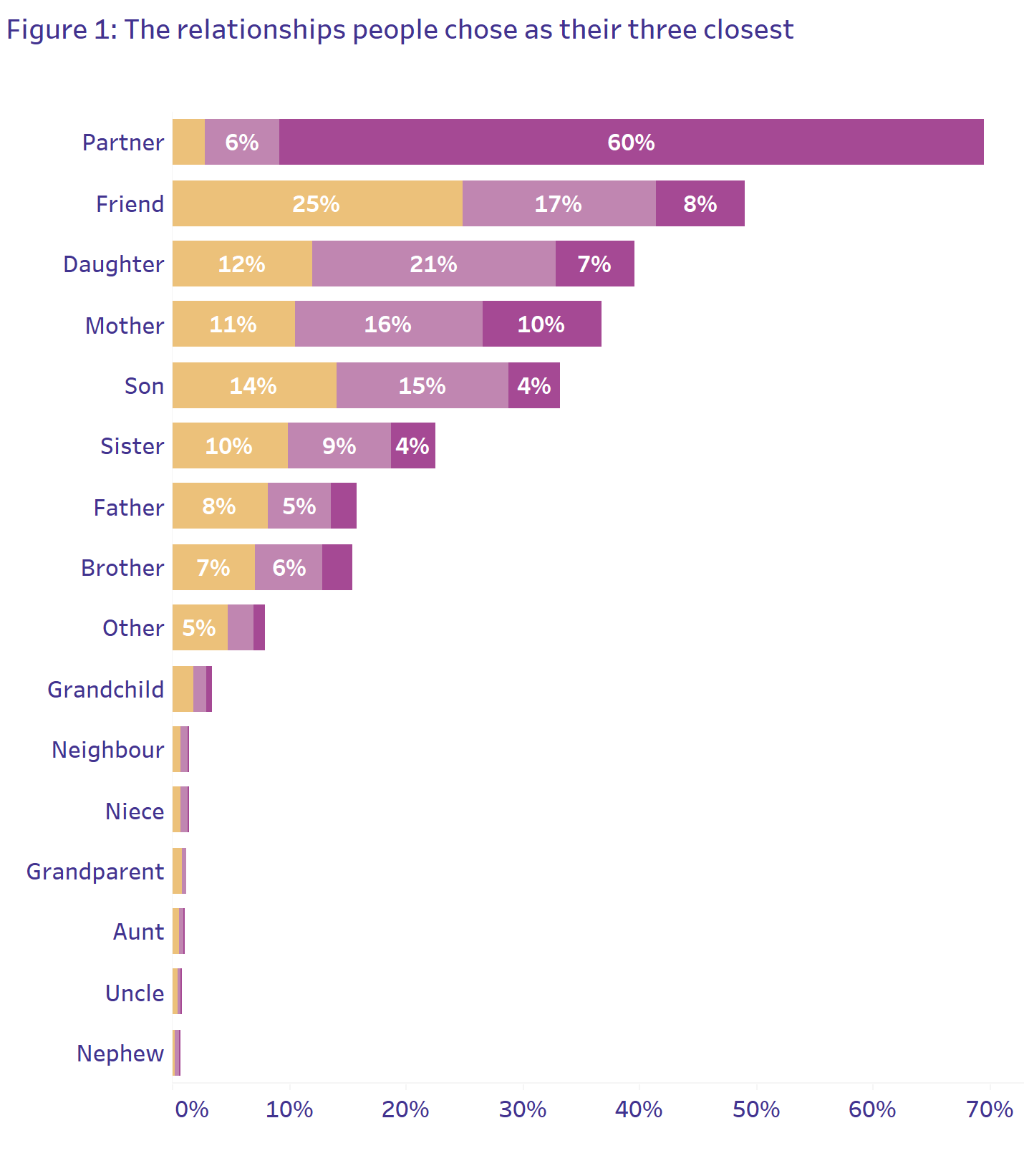

- Partners, mothers and friends play a central role in many peoples’ lives. 77.8% of Australians chose one of these relationships as their most important.

- People are more likely to identify the relationships with the women in their families as their the most important.

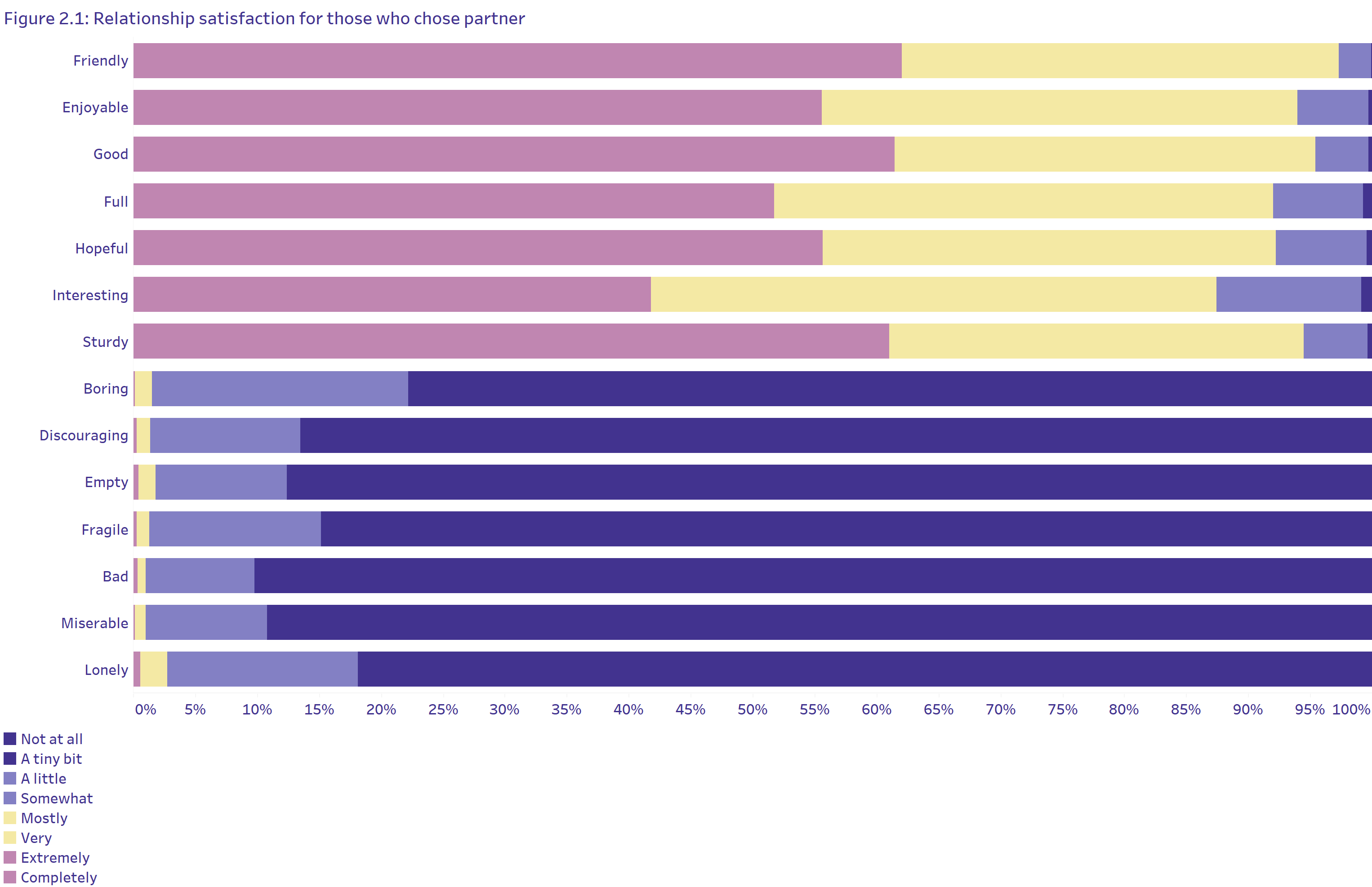

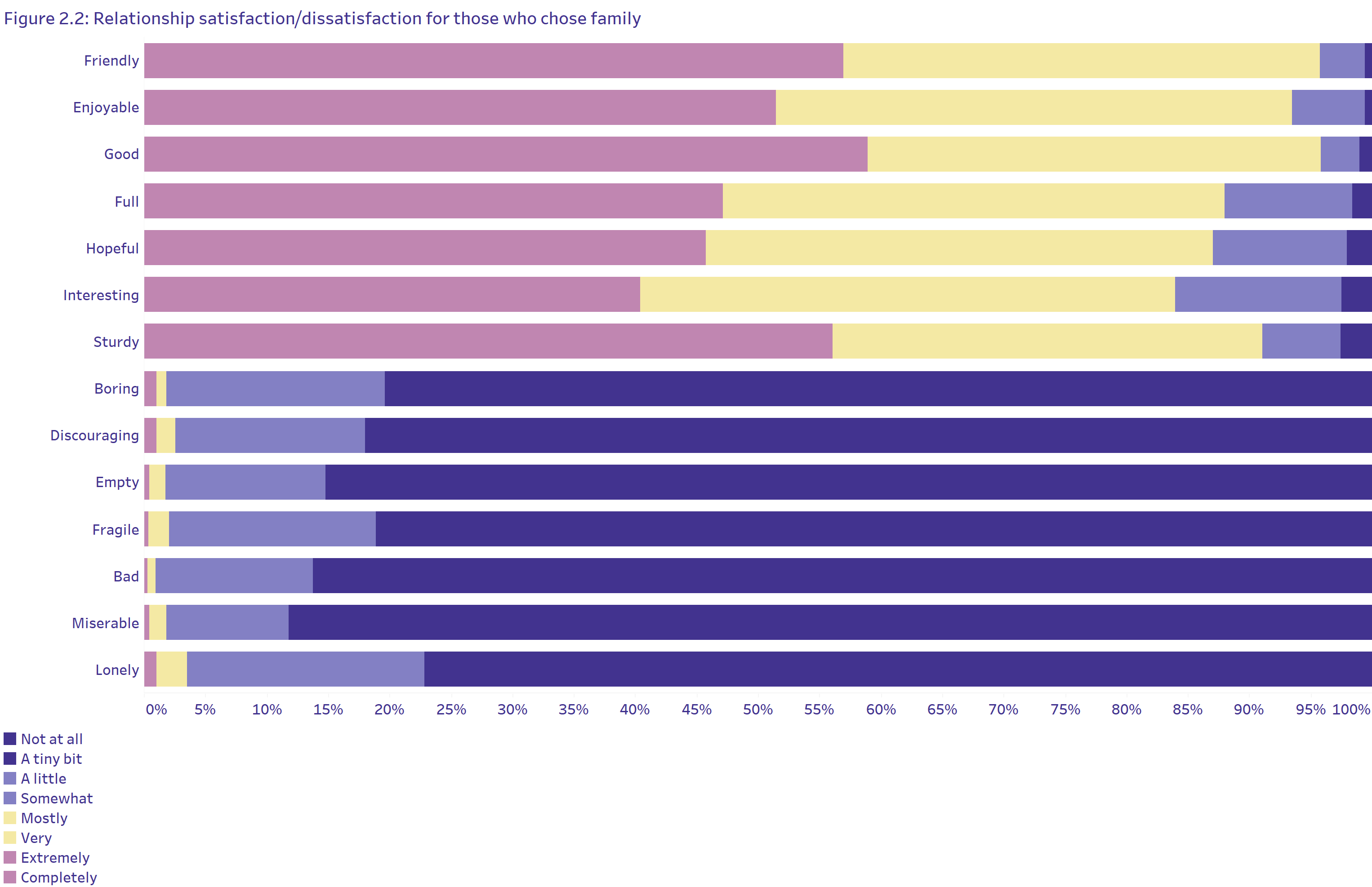

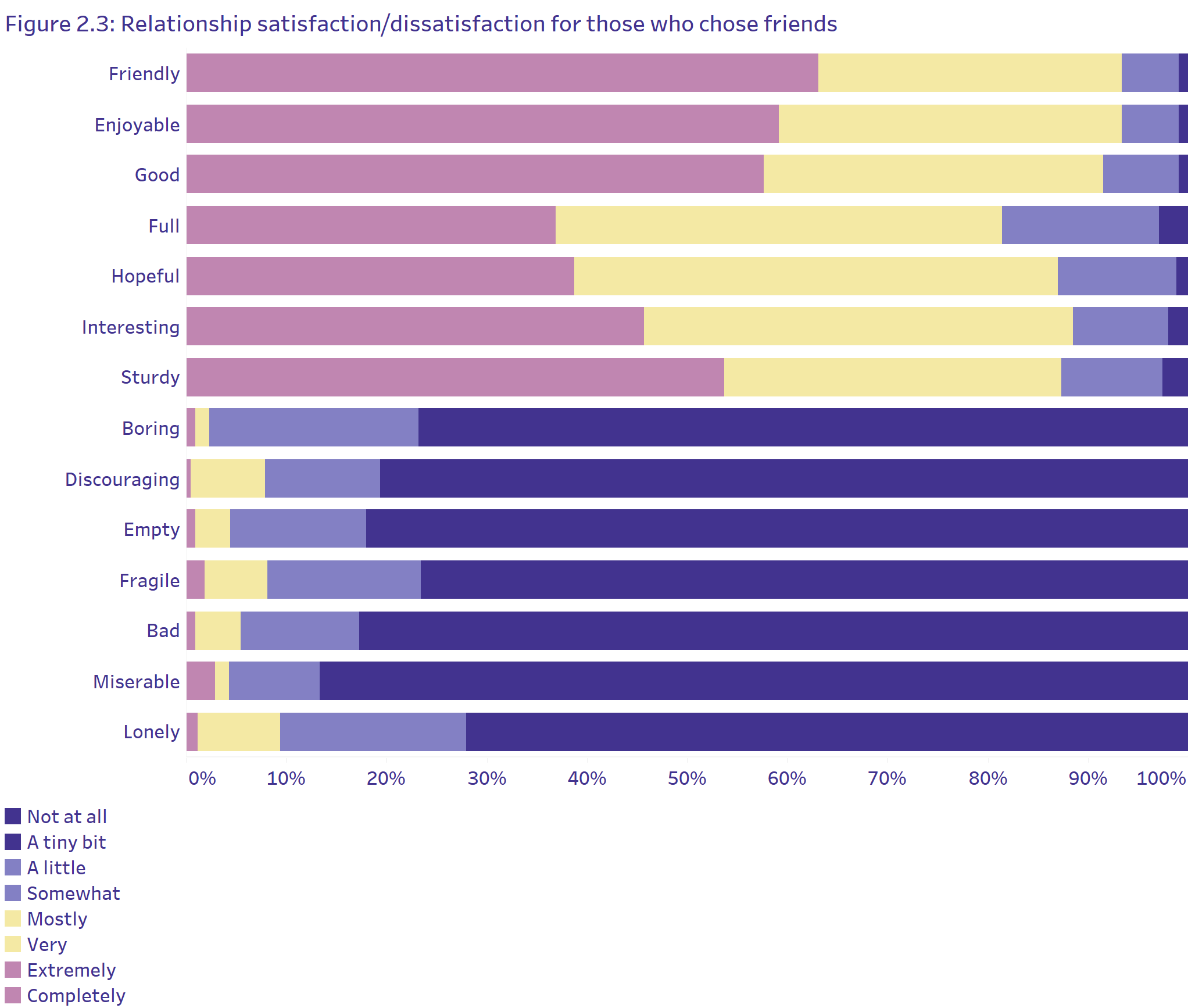

- People who selected their partner as their most important relationship demonstrated the highest level of relationship satisfaction, compared with those who selected family or friends.

- Almost all Australians identified a relationship that is satisfying. 53.3% were completely satisfied with their important relationship.

- Having fun, spending time together and communicating openly about problems in your most important relationship lead to relationship satisfaction.

- While having lots of disagreements in your most important relationship led to a reduction in relationship satisfaction.

Australians have a variety of important, meaningful connections

The survey consisted of three parts. In the first section, we asked people to think of the three people closest to them and from this, select their most important, meaningful relationship. We then asked people a series of questions exploring this relationship, including satisfaction and enjoyment, help-seeking behaviours, pressures their relationship faced and the strategies they used to manage these.

Sixty percent chose their partner as their most important, meaningful relationship. An additional 9% chose their partner as their second or third option. Mothers were also important figures, with 10.1% of Australians selecting them as their most important and 15.9% as their second most important person. Friends also played a key role, with 7.6% selecting them as their most important and 16.5% selecting them as second most important. For more information on which sub-populations chose which relationships, please see our fact sheets.

People are more likely to identify the women in their families as their most important, meaningful relationships

Across the ranking system, women played a significant role. 20.9% said their mother, sister, daughter, aunt or other woman in their life was the most important, only 9.1% chose a man.4 While alone, these findings may not be of concern, combined with our upcoming analysis of help-seeking and support, the findings suggest that people’s relationships to the men in their lives could be strengthened.

“In my case daughters are closer to [me] than sons. Sons tend to grow away from you as they get older.” – woman, 65-74

Why people chose this relationship

41% chose a relationship they had been in for over 10 years as their most important and meaningful relationship.

Around 1 in 10 people mentioned duration of their relationship as a key reason for selecting it as their most important. Similarly, many mentioned living together as the reason for their closeness. Others mentioned trust, respect and similar values or love, understanding and openness. When asked what people did to help them feel close, most mentioned communication and talking, or completing daily activities like child-rearing, cooking, or watching television.

Australians are very satisfied with these connections

53.3% are completely satisfied5 with the relationship they chose as the most important or meaningful

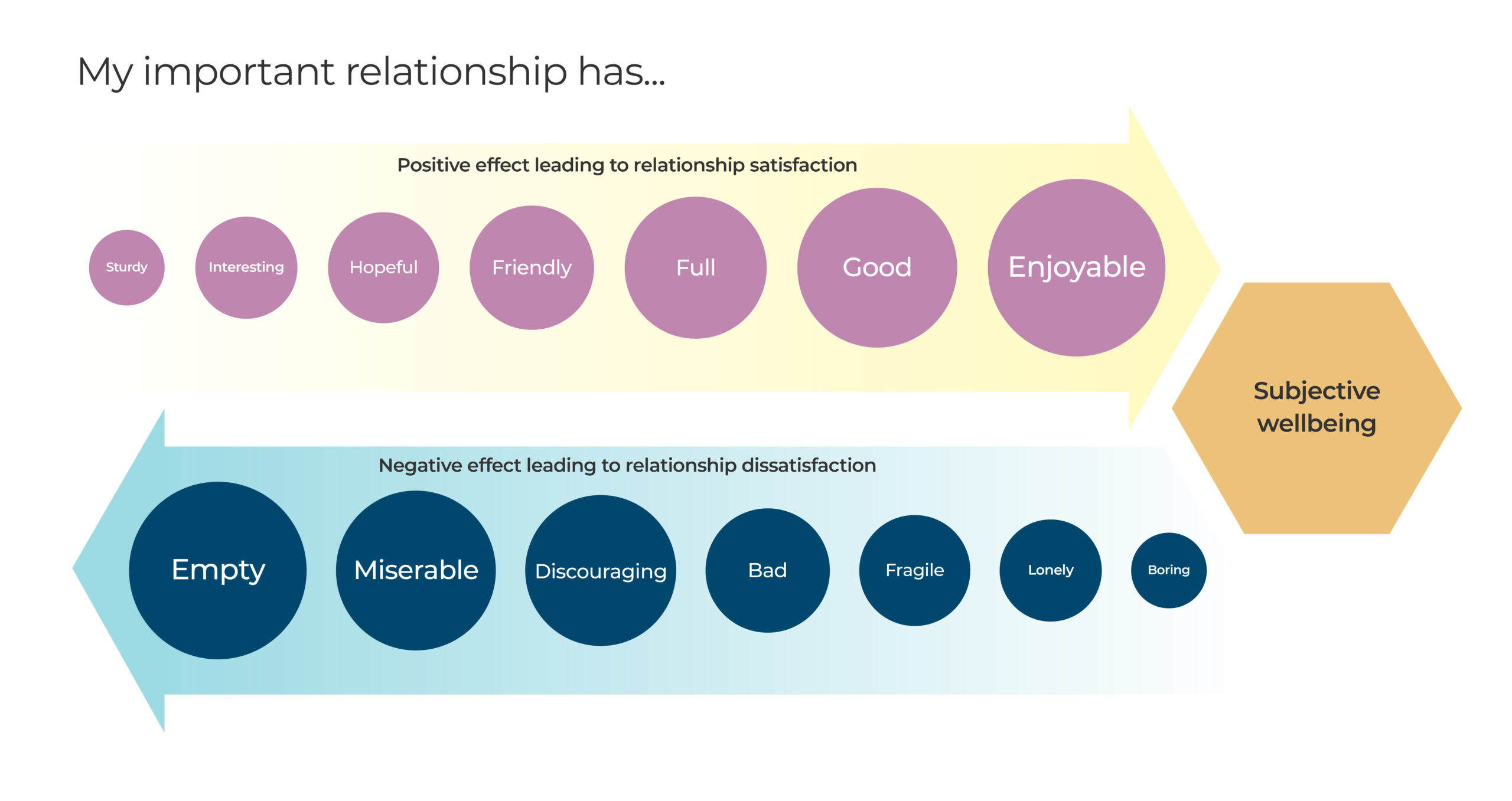

Relationship satisfaction is the subjective evaluation of a relationship and is considered one of the most crucial measures of relationship functioning. We explored relationship satisfaction for the relationship people declared as their ‘most important [and] meaningful’. Relationships Australia recognises that relationships are complex. Rather than measuring relationship satisfaction as binary, (for example, if my relationship is not good, it must be bad), we used a two-dimensional measure6 to demonstrate that satisfaction is more than an absence of negative emotion and vice versa. Respondents were asked to consider only the positive or negative qualities of their most important relationship and then state whether they felt this relationship matched the following terms.

Describing the most important relationship as ‘good’ or ‘enjoyable’ was most indicative of relationship satisfaction.8 Given the many external challenges relationships have faced in the past few years, this suggests that while people may not be 100% satisfied with their relationship, this does not equate to dissatisfaction. It also suggests that there is room for improvement. Later findings demonstrate that dissatisfaction was correlated with loneliness and lower wellbeing and poorer mental health. Services that support respectful relationships and address loneliness, wellbeing and mental ill-health provide promise that there are effective interventions that support people to address some less favourable areas, knowing that generally, Australians feel a sense of satisfaction with their most important relationships.

“[She] makes me happy. She’s someone I want to spend the most time with” – man, 25-34

“[We] enjoy each other’s company no matter what we do” – woman, 65-74

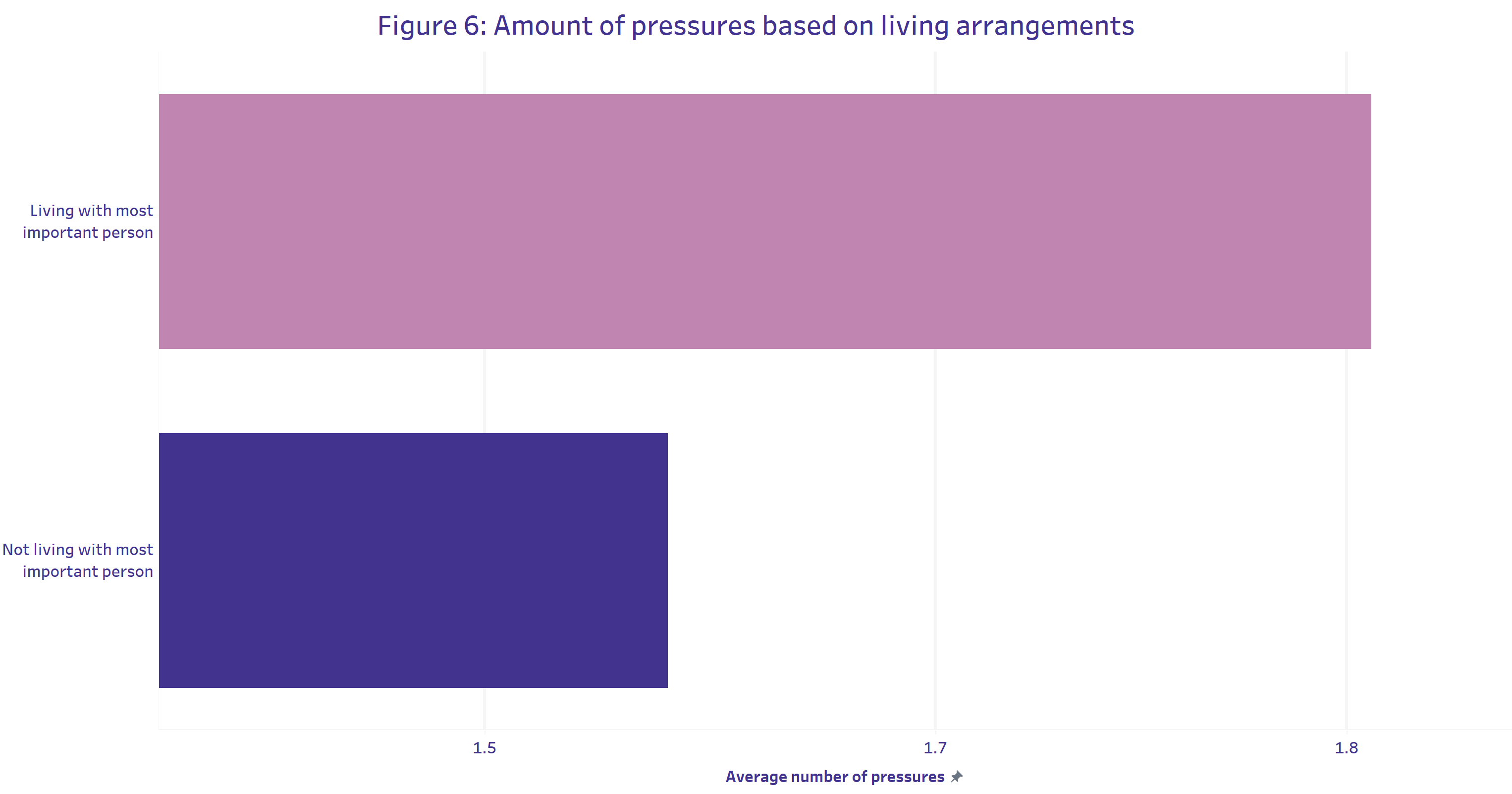

Who feels satisfied?

People who lived with their most important person were more likely to feel satisfied with this relationship than those who did not.9 However, these relationships were also more likely to face pressures. In general,10 the length of relationship did not have a substantial effect on relationship satisfaction, however those who had known each other for longer were more likely to feel their relationship was full or sturdy, while individuals in shorter relationships were more likely to describe them as bad, lonely, discouraging, and/or fragile.

We found that people who identified their partner as their most important relationship (60.1%) were more satisfied with this relationship than those who identified a family member (31%) or friend (7.6%) as their most important. Those who chose a friend were also less satisfied with this relationship than those who chose a family member. Although men were more likely than women (65.7% versus 54.6%) to choose their partner as their most important person, there was little difference between levels of satisfaction with partner relationships between men and women. Additionally, across all important relationships, men were less satisfied with their most important relationship (48.4% of men completely satisfied versus 56.2% of women). This, coupled with other findings about men throughout the report, suggests that boys and men require more support to create stronger connections.

This may be because the tool we used to measure relationship satisfaction was designed with partners in mind. Family relationships and friendships are established on different foundations and the statements participants were asked to agree or disagree with may not predict the same relationship experience. However, given our work in the familial space, Relationships Australia notes with some concern that familial relationships were less likely than partner relationships and friendships to be described as sturdy, enjoyable and hopeful and more likely be described as lonely, boring, and fragile.11 Irrespective of the original intention of this measure of relationship satisfaction, these findings suggests that familial relationships require additional support to ensure that they remain positive, caring connections. This becomes especially important when we consider how these descriptions affect wellbeing.

“I feel my friends are my chosen family and there are a lot who I would go to first for support or help.” – Woman, 25-34 years

Who feels dissatisfied?

People who agreed with all the negative terms about their important relationship are considered dissatisfied.12 Only 0.1% of the population met these criteria. In fact, 34.3% didn’t resonate with any of the statements. 13 When we looked at specific terms in the measure, we found that describing a relationship as discouraging or empty was most likely to produce relationship dissatisfaction.14 Promisingly, less than 2% described their most important relationship with these terms. It is both reassuring, and a testament to the resilience of people, to find that 98% of respondents15 had meaningful relationships.

How can we improve relationship satisfaction?

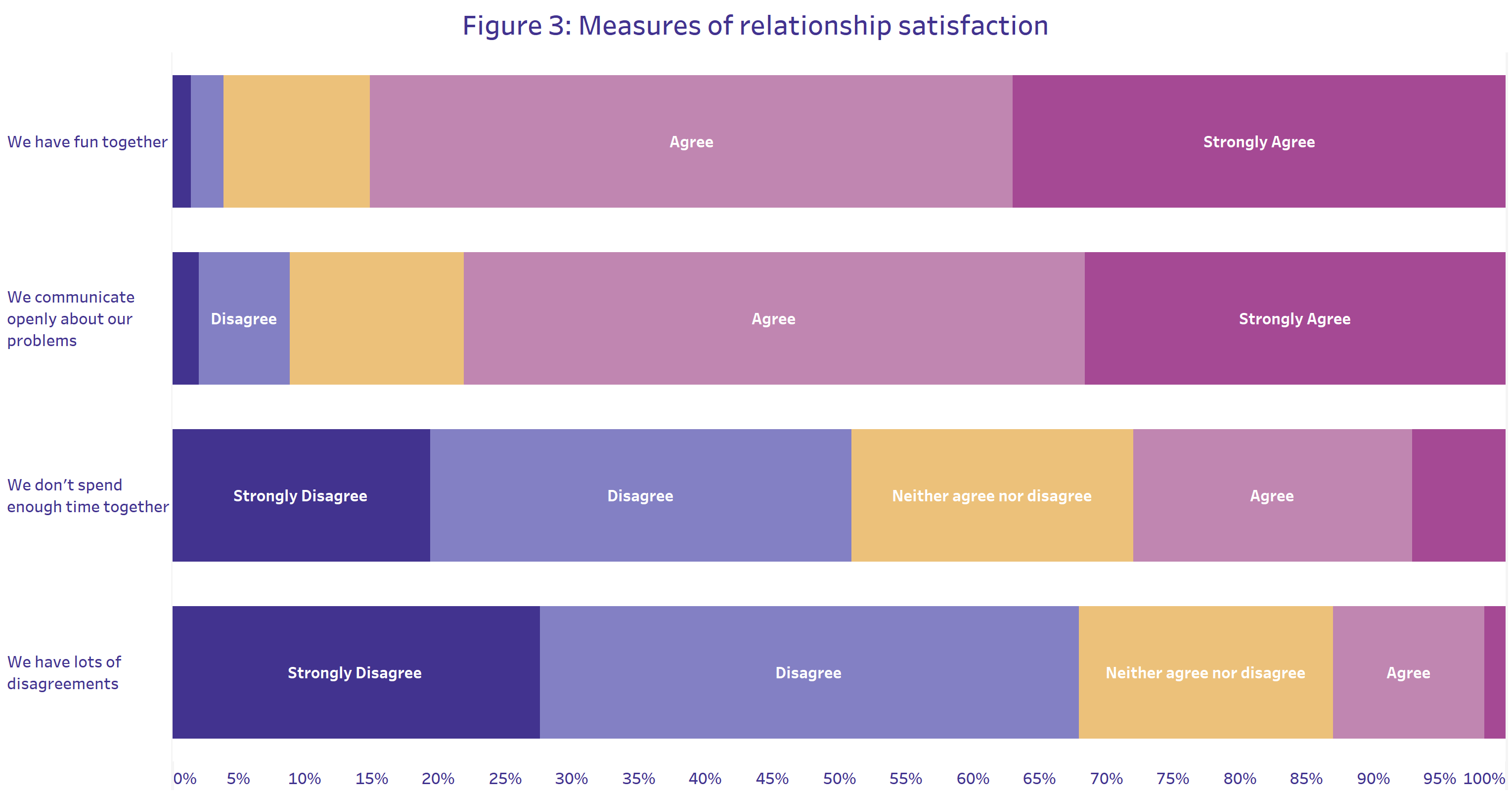

The presence of certain behaviours in a relationship can provide insight into how satisfying the relationship is. Relationships Australia asked respondents several behavioural questions to provide further context to the relationship satisfaction measure.

15% said they had lots of disagreements in their important relationship

Interestingly, describing a relationship as ‘boring’ was the only statement that was not linked with more disagreements. This perhaps suggests that a ‘boring’ relationship is not necessarily negative in this respect. Conversely, describing a relationship as ‘friendly’ was the only statement that was associated with fewer disagreements.

Intriguingly, having fewer disagreements didn’t necessarily make a relationship more satisfactory, suggesting that it is not the presence of the disagreement but perhaps the way in which it was responded to. Relationships Australia recognises that disagreements can be a common element of a respectful relationship; therefore, rather than focusing on preventing or minimising disagreements, understanding how to navigate disagreements in a respectful manner is key to building more satisfying relationships. Relationships Australia has significant experience delivering evidence-based services which deliver these outcomes.

“[I am] not allowing disagreements to spoil all that is good.” – man, 65-74

“[They are my most important person] because we are bonded. Fight like hell. Disagree on everything, and I do mean everything, except politics.” – woman, 55-64

“[We] argue about the small things but the big things we are very sympathetic to each other.” – woman, 55-64

We found that those who communicated openly with their most important person were more likely to feel satisfied with this relationship.17

Similarly, we found that those who feel that they don’t spend enough time together were also less satisfied with their relationship.18 28.9% felt that they did not spend enough time with their most important person. Lastly, 84.8% of people agreed that they have fun in their most important relationship. Having fun in a relationship is the strongest predictor of relationship satisfaction that we found in this analysis.19

76.9% communicate openly about their relationship problems.

These measures were developed in consultation with Relationships Australia staff based on statements and inductive reasoning from their work supporting relationships. These findings let us say with some confidence that having fun, spending time together and communicating openly about problems are all important aspects of a satisfied relationship. However, none of these were so strongly correlated with satisfaction that we can say ‘this is the key to a happy relationship’. Conversely, we can also say that disagreements don’t necessarily lead to dissatisfaction. Our experience tells us that relationships are complex. While improving fun, time together and communication may improve the relationship, not all people who do this will have a happy, functioning relationship. We also recognise that weaknesses across these measures can also be symptomatic of other pressures in our lives. For example, people who work a lot and have many caring responsibilities may not have the time or energy for fun. Ultimately, these findings are indicative of the role external pressures are playing on relationship satisfaction. We will explore the role of external pressures play on a relationship further in the Relationship Pressures section on the report.

Relationships and subjective wellbeing

Key points

- Satisfying relationships are good for wellbeing. The more satisfactory someone’s important relationship was, the better their subjective wellbeing.

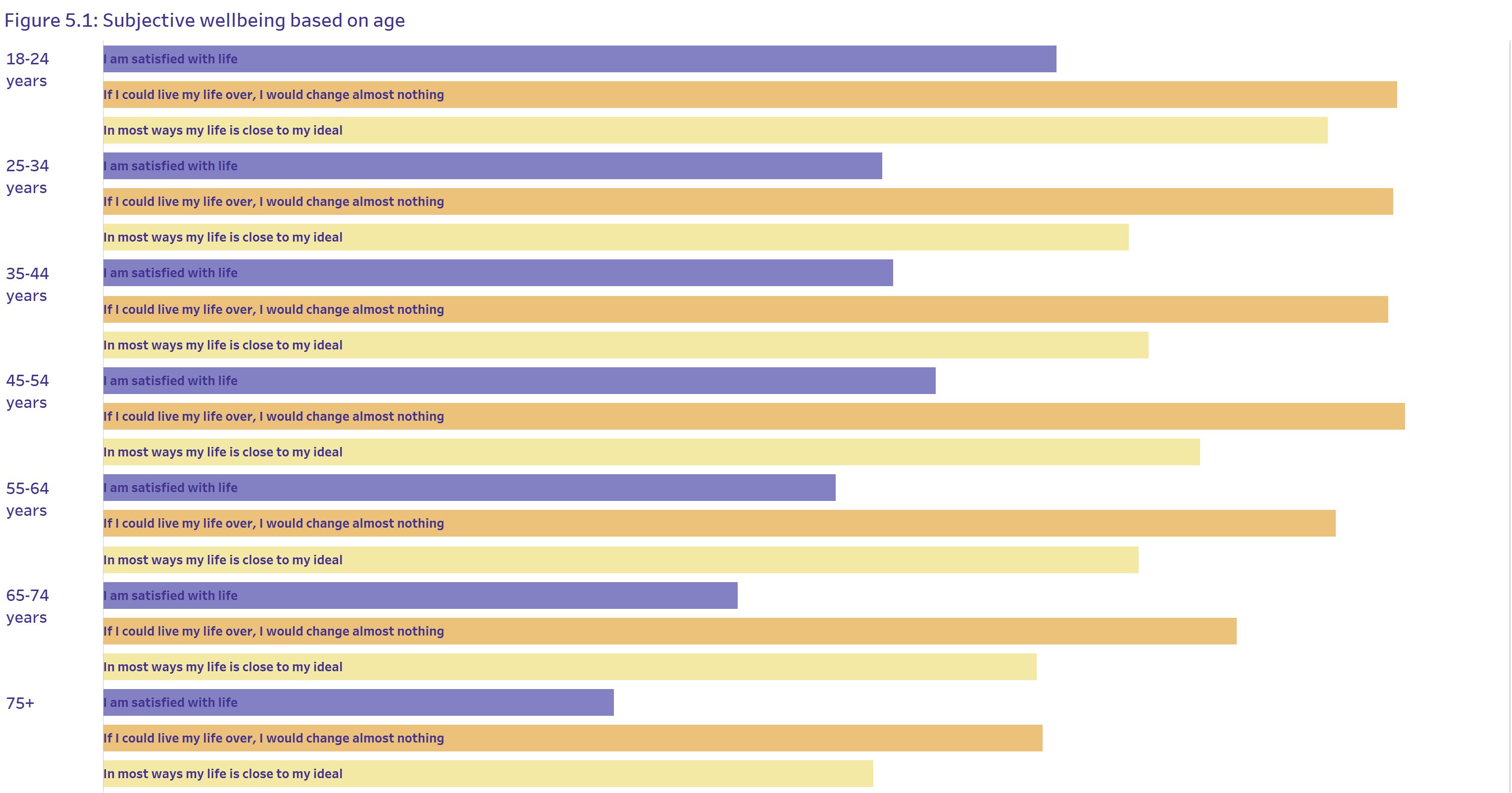

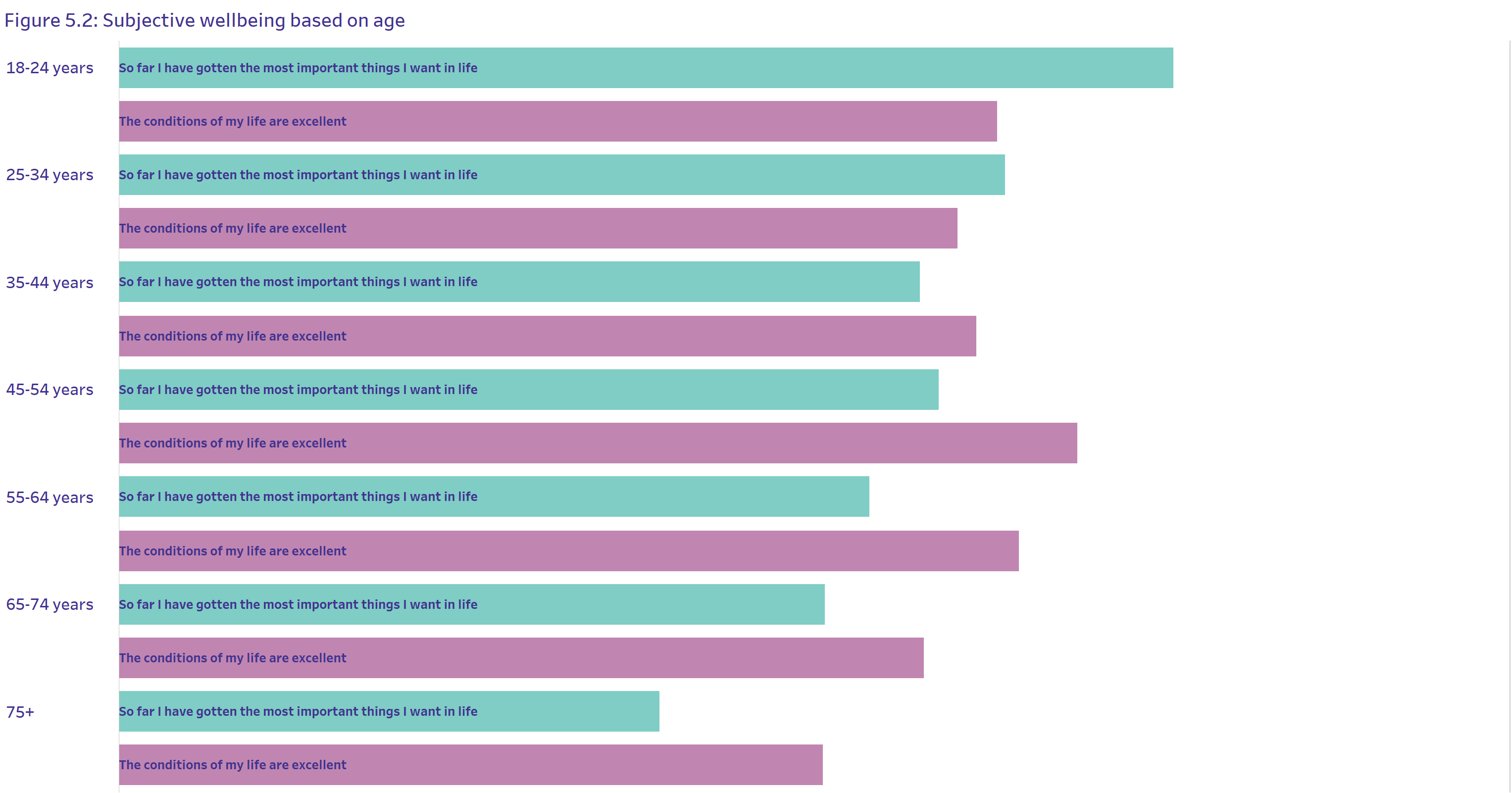

- Generally, older people were more satisfied with life than younger people. This was most prevalent when comparing the responses of the oldest and youngest groups.

- The combined effects of caring duties, deteriorating health and relationship breakdown reduces subjective wellbeing, especially for middle aged people (those aged 45-64).

Satisfying relationships lead to greater subjective wellbeing

Relationship satisfaction isn’t just important for the health of relationships; it also predicts satisfaction with life. Life satisfaction is another way of describing subjective wellbeing. 20 Wellbeing can be measured by looking at observable concepts like access to housing and healthcare or subjective concepts like feelings of happiness. Subjective wellbeing refers to how people understand and evaluate their life. It is affected by the quality of their relationships. Feeling satisfied with life can be an indicator of other concepts like happiness, mental health and how people feel about their direction and options for the future. Therefore, improving life satisfaction can improve people’s outlook on life.

“I’m not sure who I’d identify as my closest relationship, I’ve moved around a lot recently and am not really close with anyone.” – man, 18-24

“They are all I have – I don’t have a wife…parent’s and family are long passed away” – man, 65-74

“She lives an hour away by car and we don’t see each other often” – woman, 65-74

Subjective wellbeing increased for older people. This was especially true for those aged 65+. However, the measure exploring ‘conditions of life’ broke this pattern. Our research found that middle aged people (45-64 year old’s) were least likely to agree with the statement ‘the condition of their life was excellent’. Additionally, younger people (18-44 year old’s) saw a spike in this measure of satisfaction. Middle and older aged people were more likely to agree with reflective statements about life.23 This suggests that while middle aged people may face more day-to-day struggles than the young and old, age helps people clarify and come to terms with the various changes in life and soothes worries related to what might be lacking.

The effects of ageing on relationships and wellbeing

The combined effects of caring duties, deteriorating health and relationship breakdown seems to culminate in those aged 45-64 years old. Qualitative analysis demonstrated that part of the reason for lower subjective wellbeing in those aged 45-64 years old was the conditions of their life. As people aged and relationships shifted these issues influenced their subjective wellbeing.

Our analysis demonstrated that for the ‘sandwich generation’, those caring for aging parents as well as their own children, the role of double caring responsibilities placed pressure on their most important relationship.

I am a “3 person carer, part time for aged parent & adult child plus full time for disabled adult child” I manage these pressures by “enjoy[ing] the small pleasures of life” – woman, 55-64

“we manage our time, make sure we have enough space to talk and discuss things [while caring for ageing parents and children]” – man, 45-54

“bring[ing] up our children and supporting our ageing parents…[we] don’t actually do much just as a couple without the kids and our relationship has suffered a bit” – woman, 45-54

“I put my life somewhat on hold to care for him due to his health” – woman, 55-64

To manage the ill-health of his partner one “dropped unimportant tasks…just made sure the household basics are done” – man, 55-64

“I am quite broken now. I have no interest in any relationships” – man, 55-64

“the necessary on-going contact with former husband (re child rearing and access issues) is difficult” – woman, 55-64

“As I’ve recently retired, we are doing everything together now. Hanging at home, off on holidays, being there when my loved one’s have died, being there when one of us has been very ill.” – woman, 55-64

“[we feel close] especially now that we are both retired. Previously when we both worked we tried to do everything together on the weekend because during the weekdays we were ships passing in the night” – woman, 55-64

Relationship Pressures

Key points

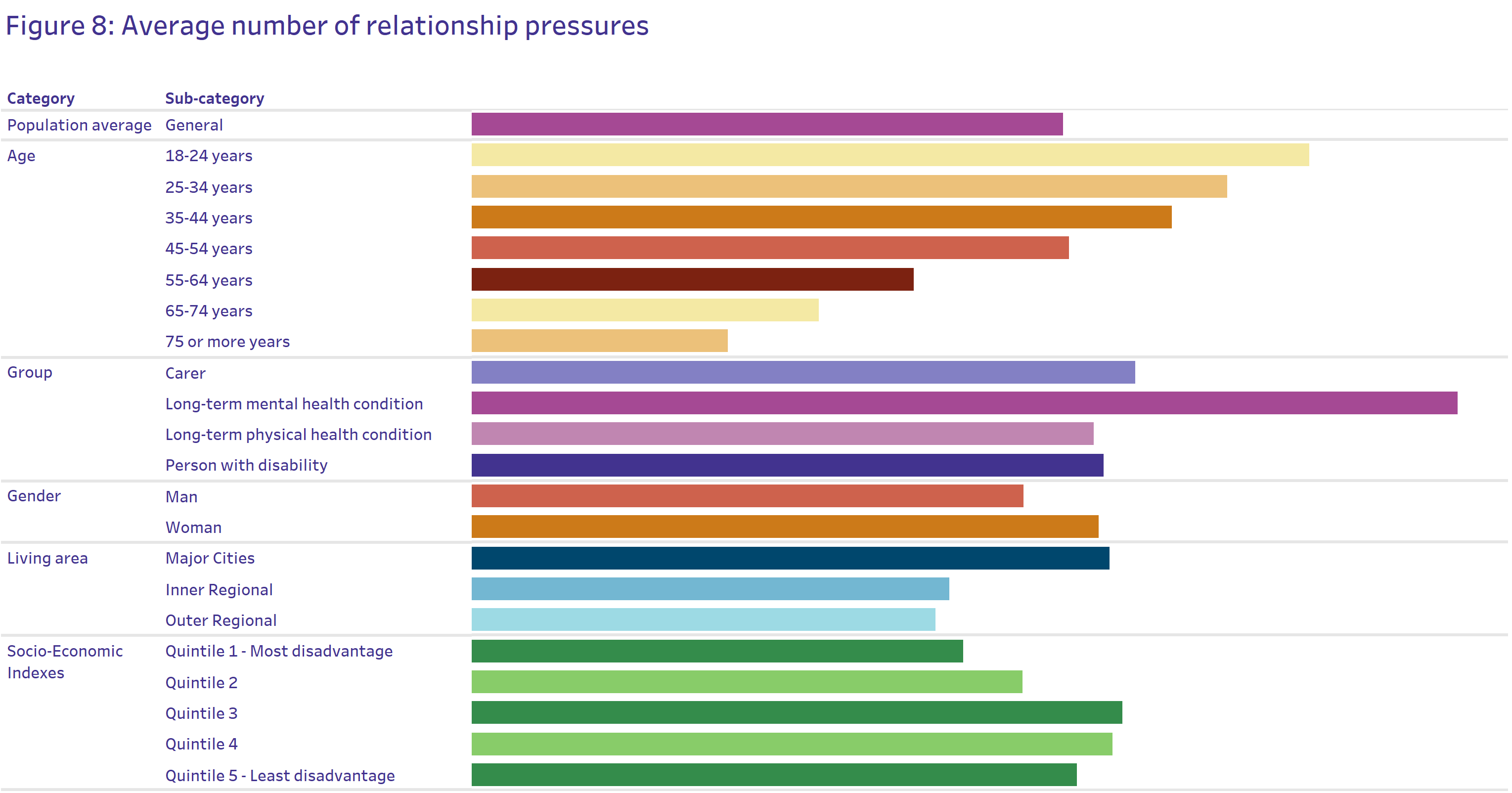

- 71.9% of Australians faced relationship pressures in the last six months. The average person encountered between 1 and 2 pressures in their most important relationship.

- The pressures facing Australian relationships are varied and intertwined, but many relate to the ongoing effects of the pandemic and the rising cost of living.

- The effects of mental ill-health were pervasive across relationships, being a major pressure in itself, and a cause and consequence of other pressures.

- People with long-term mental and/or physical health conditions faced the most pressures.

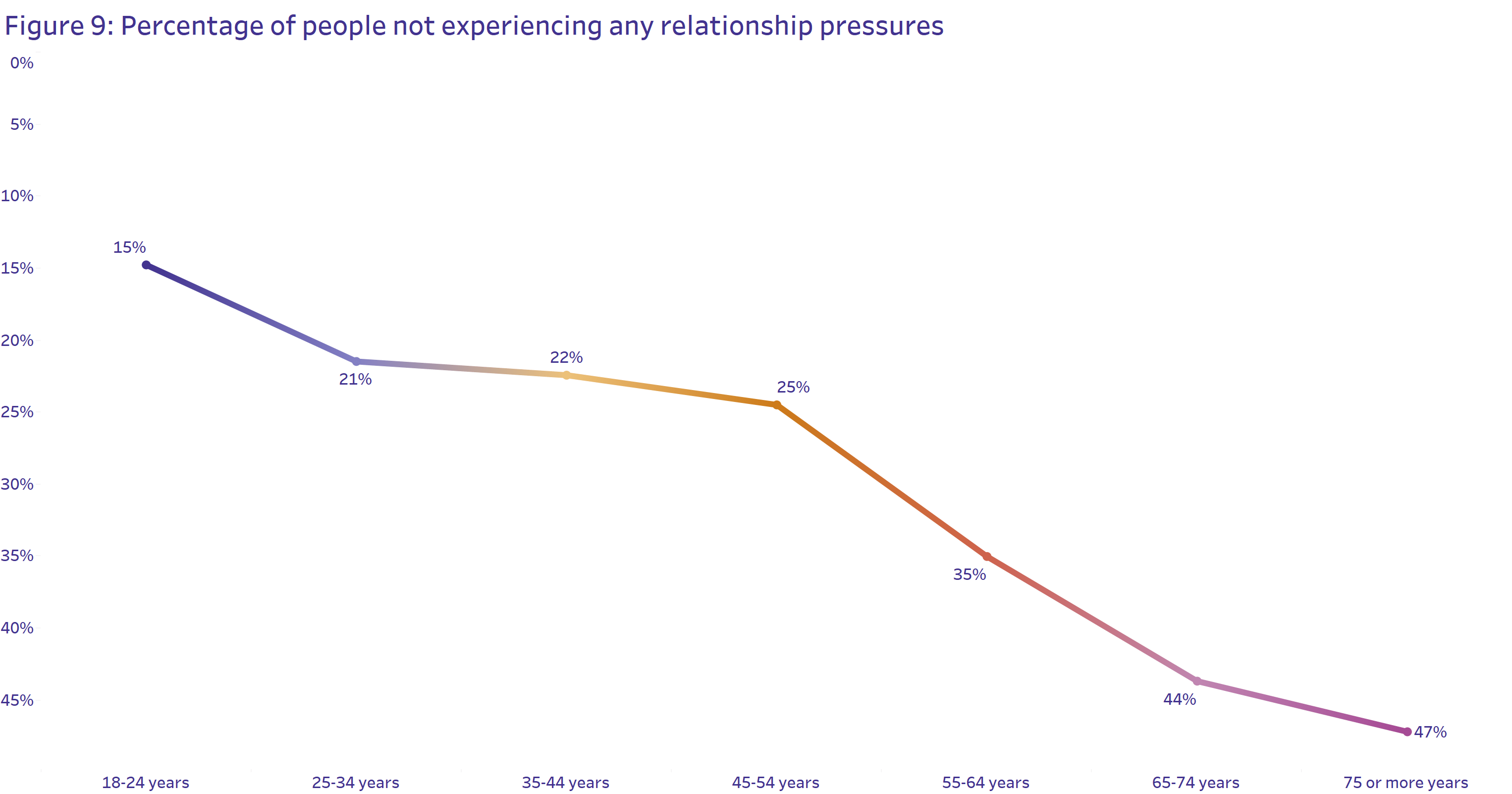

- Older people were less likely to face pressures in their most important relationship. 42% of those aged 55 or older faced no pressures in their important relationship in last six months.

- Relationship pressures are associated with reduced relationship satisfaction, subjective wellbeing, and higher levels of loneliness.

What is placing pressure on Australian relationships?

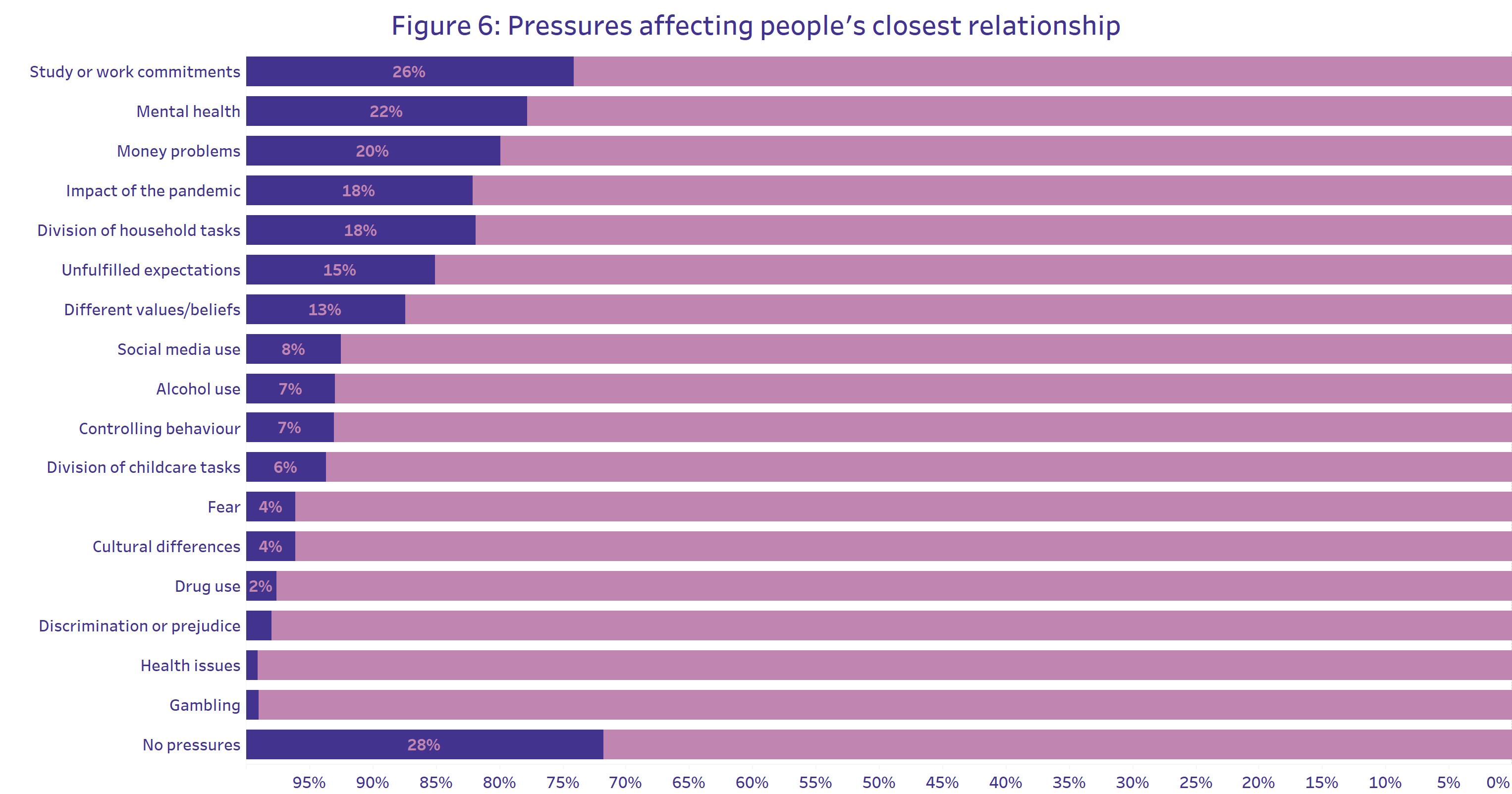

Relationship pressures can be internal or external factors which can challenge the relationship and often require strategies to manage their effects. Respondents were asked to identify which pressures their important relationship had experienced in the last six months. The most common pressures facing Australian relationships are study or work commitments (affecting 25.8%), mental health (affecting 22.1%) and money problems (affecting 20%). One in five (19.2%) Australians said that study or work commitments were the biggest pressure on their most important relationship.

22.1% said mental health placed pressure on their most important relationship in the last six months.24

How do life circumstances affect relationship pressures?

The length of people’s most important relationship also influenced the type of relationship pressures they faced. Those who had been in their most important relationship for 5 years or less were most likely to cite study or work commitments (43.3%) and mental health (41.7%) as pressures, whereas those in medium-term relationships (between 6 and 30 years) were more likely to cite the division of household tasks (29.5%) and study or work commitments (29.3%). Finally, those who had been in their most important for over 30 years were most likely to say they had no pressures affecting their relationship in the last six months (39.3%); however, for those in this age group who were affected by external pressures, the impact of the pandemic was the pressure causing the most distress (14.8%).

People with children had similar pressures to the broader population;25 however, there were differences among people with children at home versus those with teenagers at home. For people with children (under 13), the division of childcare tasks was a unique issue (affecting 66.1%), whereas the division of household tasks were more likely to be a relationship pressure for people with children aged 13+ (affecting 31.1%).26

“[To manage the pressure we are] openly speaking about the frustrations of raising teenagers, especially during the pandemic” – woman, 45-54

“[I damaged] my own career to buffer [the] complete lack of support for working parents with young school children during lockdowns; turned to professional help (psychologist) to manage mental health problems from triple burden (work, homeschooling, caring for children and maintaining healthy family life)” – woman, 45-54

Who is facing the most relationship pressures?

Certain groups were more likely to experience pressures. In particular, the pervasiveness of relationship pressures for young people, carers, and people with long-term mental health conditions was apparent.

71.9% of Australians faced relationship pressures in the last six months. The average person encountered between 1 and 2 pressures in their most important relationship in the past six months.27 8.4% of the population faced five or more pressures at once.

In comparison, 87% of people with long-term mental health conditions faced relationship pressures, often facing 2 to 3 pressures at once. More than half (53.1%) faced 4 or more pressures at once.

While there was only a minor gendered difference (73% of women versus 70.6% men experienced relationship pressures), women were more likely than men to cite mental health as a relationship pressure (26% versus 18.1%). There were no other significant gendered differences across pressures.

“My long-term mental health conditions have impacted our relationship significantly over the years. My husband and I have both sought professional help at different times, and grown in our abilities to remain present and compassionate. My husband makes more effort to go out…to care for his own mental health [and] we make sure to go out together as I am able.” – Woman, 55-64 years

86.5% of young people (18-24 years) faced relationships pressures and 30.2% of young people faced four or more pressures at once. Almost half (49.1%) of young people said work or study commitments were affecting their important relationship. Young people were also more likely than the rest of the population to select different values or beliefs as a relationship pressure (23% versus 10.7%). This pressure had a negative correlation with age, older people were less likely to select this as a pressure. The pressure of ‘unfulfilled expectations’ also followed this pattern, affecting people younger people at twice the rate of older Australians (19.4% for those aged 44 years or less, 10.6% for those aged 45+).

“We are a cross cultural relationship (country anglo and person of colour) we have very different experiences of the world, different expectations of what is acceptable with regards to social justice or even when one of us sees something as prejudice and the other sees it as normal. Our strategy has been to just keep talking about it, life long learning” – woman, 35-44

“[I am] lowering my expectations, accepting reality”– man, 45-54

Across our analysis, we found that those with long-term physical health conditions faced the most pressures at once. This group experienced an average of 2.95 pressures concurrently.

“When somebody has a health event, you can only take one day at a time.” – woman, 55-64

“I am the one diagnosed with cancer. I’m both optimistic and stoic regarding how the treatment will go. My wife is very edgy about my illness – too much Dr Googling. Through the cancer centre I’m attending, she has been referred to a psychologist to talk things though.” – man, 65-74

The effect of pressures on relationships

Relationships Australia has found that experiencing relationship pressures had a significant effect on people’s health and wellbeing. People who experienced pressures in their important relationship had lower relationship satisfaction.28 Relationship pressures also reduced people’s subjective wellbeing.29 Additionally, people who faced relationship pressures were more likely to feel lonely or say they didn’t feel loved30.

While we recognise that pressures are a regular part of relationships, the enhanced role pressures play in some sub-populations and the effect of compounding pressures is of concern. Relationships Australia recognises that even ostensibly ‘internal’ pressures, such as division of childcare tasks, are impacted by external pressures like the rising cost of living and the need to work more to manage this. Relationships Australia provides a variety of services which support people to develop resilience and dyadic coping strategies in the face of relationship pressures. Although our work focuses on supporting people to manage these pressures in productive ways, it is also important that policies protect especially vulnerable Australians from the compounding effects of internal and external pressures.

“I’m not managing it. There is only so much money I have and I cannot spend more on any outings. It all has to go to bills and boring crap. I wish our world was different.” – woman, 35-44

“Our house had been damaged in the flood – and most of our issues are to do with this. Money, work, getting old are also causing problems.”– woman, 55-64

“With the cost of living going up so quickly (especially petrol) it’s not easy” – man, 65-74

“[We have a] mutual love and affection that has become so evident as a result of helping each other cope with natural disasters (drought, bushfires and then floods – climate change) and COVID” – Man, 55-64

Who doesn’t face any relationship pressures?

1 in 4 Australians (28.2%) stated that they faced no pressures in their relationship over the past six months. Relationship pressures decreased with age. Older people were less likely to face pressures in their most important relationship. Almost half (49.5%) those aged 75+ faced no relationship pressures over the past six months.

42% of those aged 55 or older faced no pressures in their important relationship in last six months.

Similarly, older people had better subjective wellbeing, lower levels of loneliness, and they rated their mental health as better, suggesting that age plays a significant role in the health and wellbeing of their relationships.

How people managed pressures

Loneliness

Key points

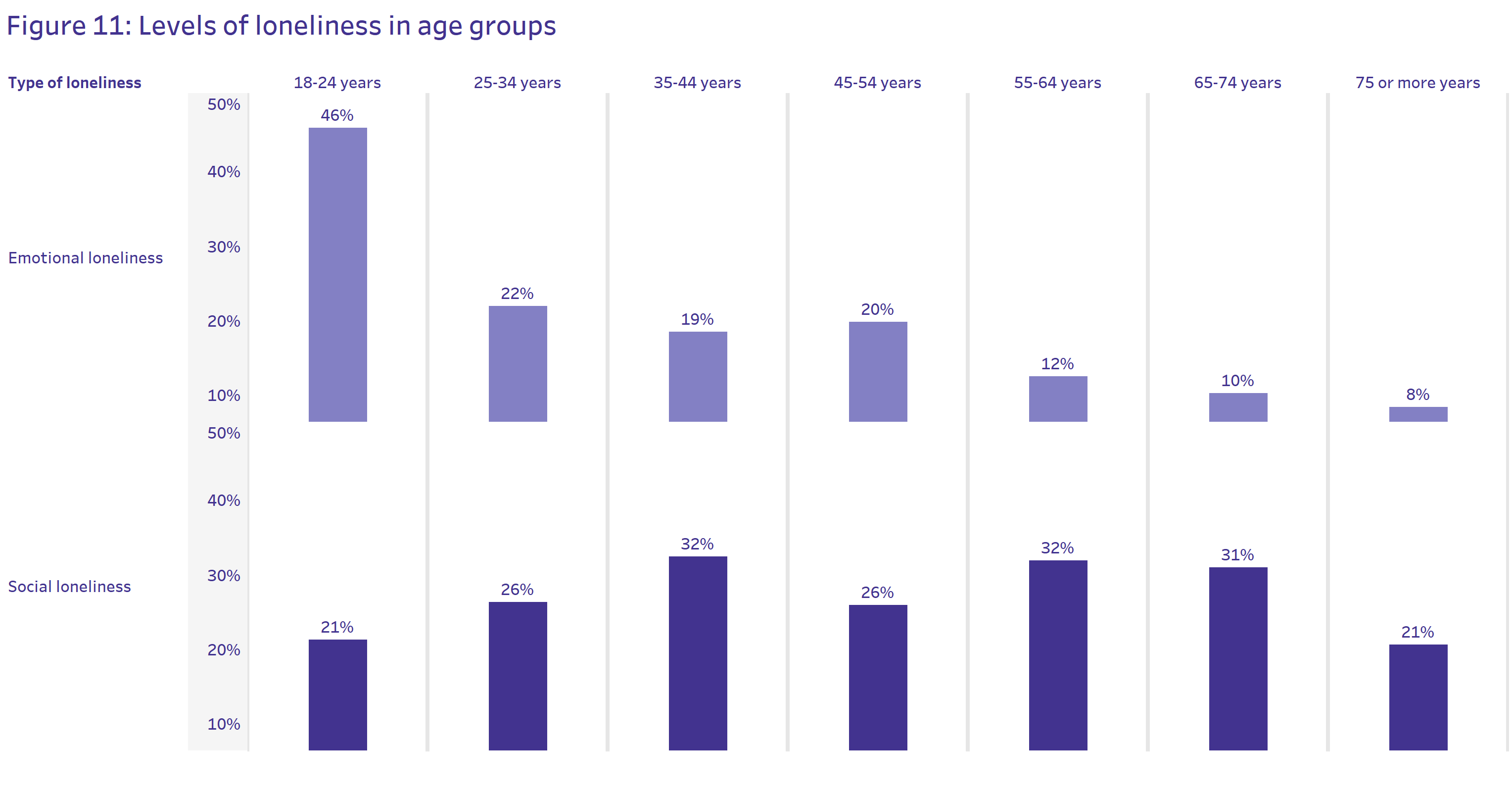

- Loneliness appears to be increasing. While all measures of loneliness have increased since 2018, social loneliness has increased the most.

- One in five Australians disclose they often feel lonely (19.9%), while indirect measures31 of loneliness suggest 23.9% of Australians are lonely.

- Almost half (45.9%) of young people (18-24 years) are emotionally lonely. This was the highest prevalence of loneliness across all cohorts that we analysed.

- People who chose their partner as their most important relationship were significantly less emotionally lonely than those who chose a family member or friend.

- Many sub-populations felt lonelier at higher rates than the population. Across these groups, emotional loneliness was especially high.

- Loneliness negatively affects relationship satisfaction and subjective wellbeing. People who were lonely had reduced relationship satisfaction and were less likely to agree that they were satisfied with life.

Updating our previous research into loneliness

Loneliness has been described as an epidemic in Australia. In 2018, Relationships Australia released a report exploring loneliness in the Australian population.32 This report found that one in six Australians were experiencing emotional loneliness, while one in ten lacked social support.33 While loneliness is a subjective experience, it both stems from and can be causative of other relationship issues. For example, Relationship Indicators found that people experiencing relationship pressures were lonelier than those who didn’t face relationship pressures.34 This group also measured higher on the emotional and social loneliness scale,35 suggesting that experiencing relationship pressures has an effect on loneliness across the spectrum. Additionally, people who felt emotionally or socially lonely, or acknowledged they often felt lonely had lower relationship satisfaction and subjective wellbeing, suggesting that loneliness has a complex relationship with other measures of health and wellbeing.

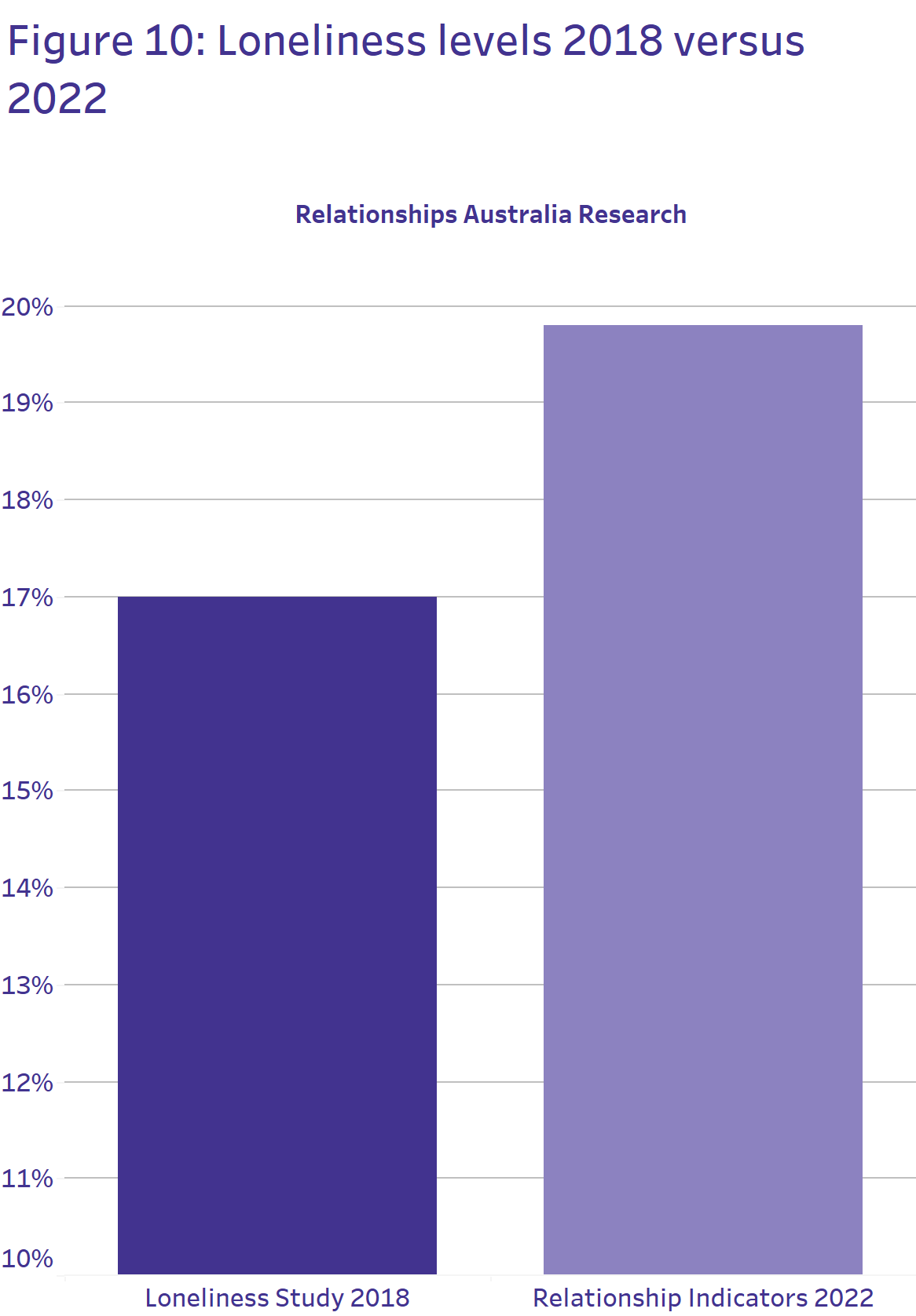

How many Australians feel lonely?

1 in 5 Australians (19.9%) said they often feel lonely. Compared with our 2018 report which found loneliness sitting at approximately 17% across the seven years prior (2009-2016), loneliness appears to be increasing. When exploring indirect measures of loneliness,36 we found 23.9% were considered lonely. Although our previous research explored long-term loneliness, and our new report explores loneliness at a point in time, this increase in loneliness is reflected in other pieces of research, such as those produced by Ending Loneliness Together.

1 in 5 Australians reported often feeling lonely. 37

Loneliness is not necessarily equivalent to social isolation. Emotional loneliness is the lack of a significant person with whom you have an attachment to, whereas social loneliness is the lack of a larger support network. We employed the six-item scale developed by DeJong Gierveld to explore these concepts. Our analysis found concerningly high levels of social loneliness.

28% are experiencing social loneliness

Almost a quarter of Australians (24.4%) agreed with the statement, ‘I miss having people around’. However, of the three statements,38 our analysis found that this was least likely to influence social loneliness. This could be due to the transformative effects of the pandemic on socialising and our ability to be alone. Furthermore, levels of social loneliness are much higher than emotional loneliness, something which could also be attributed to the ongoing effects of the pandemic. Based on these numbers, Relationships Australia believes that loneliness levels are increasing, especially levels of social loneliness.

1 in 5 (19.8%) are feeling emotionally lonely.39

Which Australians are more lonely than others?

As reported in 2018, men continue to experience slightly higher rates of loneliness compared to the population. One if five men (20.3%) feel emotionally lonely, and one in three men (32.3%) are socially lonely.40 Despite this, when asked directly,41 only 18.3% of men said they often feel lonely. Men were also less likely to be chosen as someone’s important person and more likely to select their partner as their most important relationship.

45.9% of young people (18-24 years) are emotionally lonely

Young people had the highest levels of emotional loneliness of all age brackets. Young people had the highest levels of emotional loneliness of all age brackets.Young people were also most likely to select their mother (26.9%) or friend (14.3%) as their most important person, which was correlated with higher levels of loneliness across the age spectrum.42 However, young people (18-24 years) had lower levels of social loneliness (21.4%) than those aged 25-74 years.

People who selected a partner as their most important person had lower rates of emotional loneliness than those who selected a family member or friend (12.6% for partner versus 34.8% for friend and 29.3% for family). While still statistically different, levels of social loneliness across these groups were less notable (27.3% for partner, 30.8% for friend, 28.2% for family). This suggests that for many, the partnered relationship is providing a strong source of emotional support and protecting people against emotional loneliness.

Other sub-populations also experienced loneliness at higher rates. People from a multicultural background felt lonelier than the population average.44 People with long-term mental health conditions were much more emotionally lonely, but were less socially lonely than the population.45

46.5% of people with a long-term mental health condition said they often feel lonely

People with disability had higher levels of loneliness across the spectrum,46 as did people with long-term physical health conditions47. The LGBTQIA+ community also demonstrated higher levels of loneliness.48 Carers demonstrated higher levels of social loneliness, but lower levels of emotional loneliness.49 We also found that retired people were much less emotionally lonely than the population, but had similar levels of social loneliness, which matched our age-based findings.50 We also noted that unemployed people and single parents were lonelier, which was consistent with previous findings in 2018.51 There was little difference in levels of loneliness between geographic locations.

“Living alone is lonely at times on long winter evenings after work” – woman, 65-74

“[Following relationship break-down] It is sometimes lonely. The community tends to be geared towards couples” – woman, 75+

Love and Safety

Key points

- Almost all Australians feel loved – 94.55% of Australians said they felt loved.

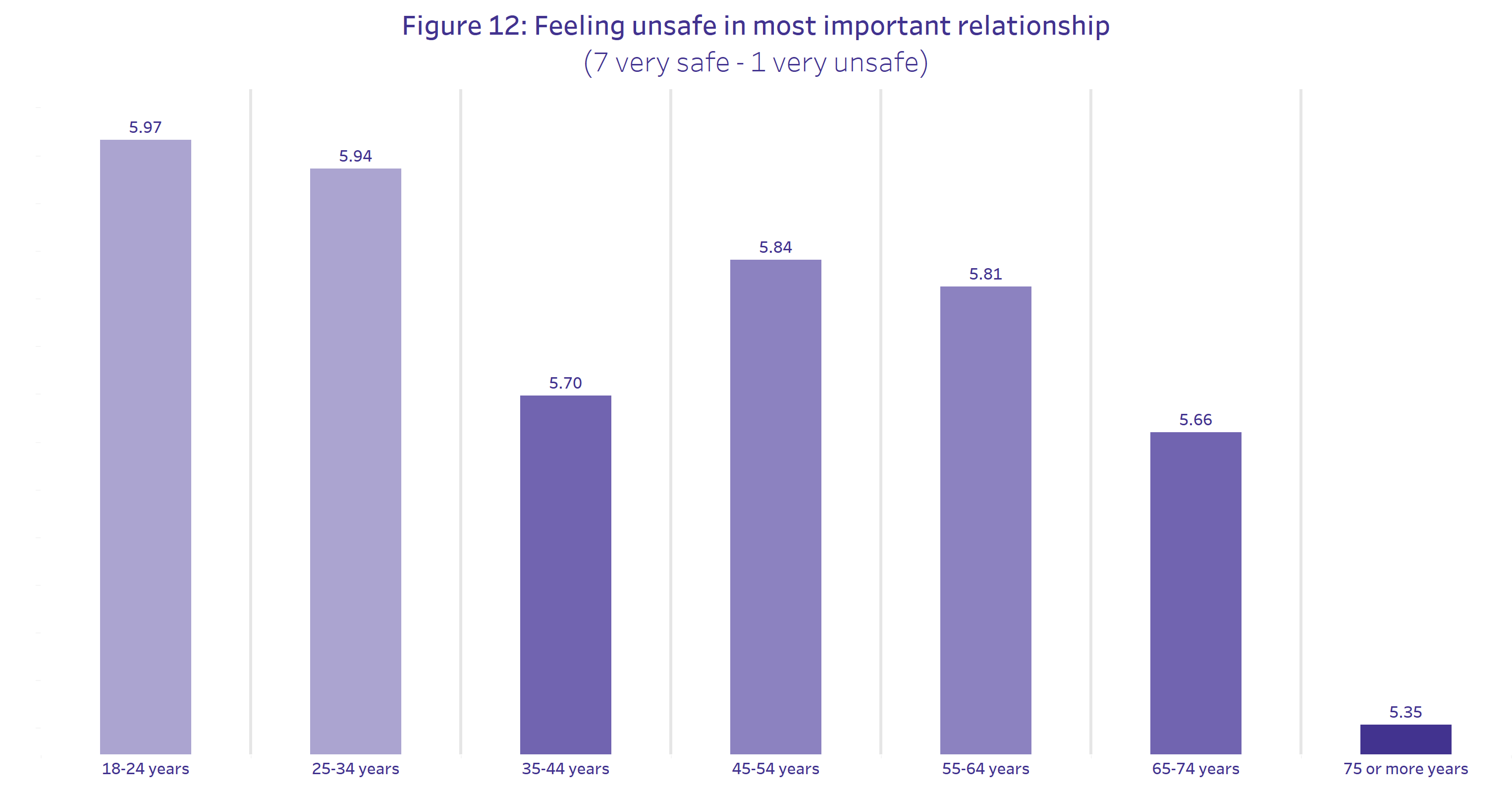

- 1.7 million Australians52 (or 8.8%) feel unsafe disagreeing with their most important person.

- Older people were more likely to agree they felt unsafe in their important relationship.

Love improves subjective wellbeing

Love is difficult to quantify, and researchers have often focused on the benefits of romantic love when exploring its advantages.53 Despite a variety of definitions, social research tends to understand love as an emotion and or set of emotions deriving from social connectedness. Our analysis found that feeling loved was correlated with all five measures of life satisfaction, suggesting that feeling loved is important for subjective wellbeing.

94.55% of Australians say they feel loved

Some Australians feel unsafe in their most important relationship

Due to a variety of reasons, the Relationship Indicators survey did not attempt to assess the prevalence of family violence or explore risk and prevention factors.56 Instead, the survey explored the concept of safety and control across a variety of measures. Controlling behaviours and feeling unsafe do not always equate to violence; however, they can be indicative of risk factors associated with family and domestic violence.57

1.7 million Australians (or 8.8%) feel unsafe disagreeing with their most important person.

This included people who chose familial relationships (nephew, aunt, sister and mother) as well as people who chose their partner, suggesting people feel unsafe in a variety of relationships.

Age affected perceptions of safety. Older people were less likely to agree that they felt safe disagreeing with their most important person. Of all age groups, those aged 75+ were most likely to state that they felt unsafe disagreeing with their most important person (16.2% said they felt unsafe). Our analysis found no discernible correlation between people who didn’t feel safe disagreeing and the number of disagreements they had, suggesting that feeling unsafe does not necessarily increase or reduce disagreements.

3.9% said fear was a pressure affecting their most important relationship

A further 7% said they experienced controlling behaviour in their most important relationship. These pressures were most prevalent in those who chose their mother, friend or father as their closest person.58 This suggests that this question was more effective at detecting controlling behaviours outside of the partner relationship. Those who identified that they experienced controlling behaviour did not appear to be from a specific group; there was no pattern across age, gender, geographic location, socio-economic index, cultural background, or educational qualification.

Our analysis also found that those who don’t feel safe disagreeing with their most important relationship were lonelier. They were both more likely to agree that they often felt lonely, and demonstrated significantly higher levels of emotional or social loneliness. In fact, a quarter 27.9% were emotionally lonely.59 Emotional loneliness refers to the lack of a significant person with whom you have an attachment to, making this especially concerning, as our analysis also found that when people feeling unsafe seek help, they are most likely to do so from family or friends. Finally, we found that 48% of people who felt unsafe in their important relationship managed their issues in this relationship on their own.60

Grief and Loss

Key points

- Experiences with grief and loss in the partner relationship led to higher rates of loneliness and additional pressures in other relationships with family, friends, and new partners.

- Those who received support from multiple sources following the death of their partner were less socially lonely and their self-rated mental health was better.

- People felt limited by their own motivation and isolation following a bereavement, making them less likely to find support.

For the full analysis, please see the Partnered Relationships fact sheet.

Who has experienced grief and loss?

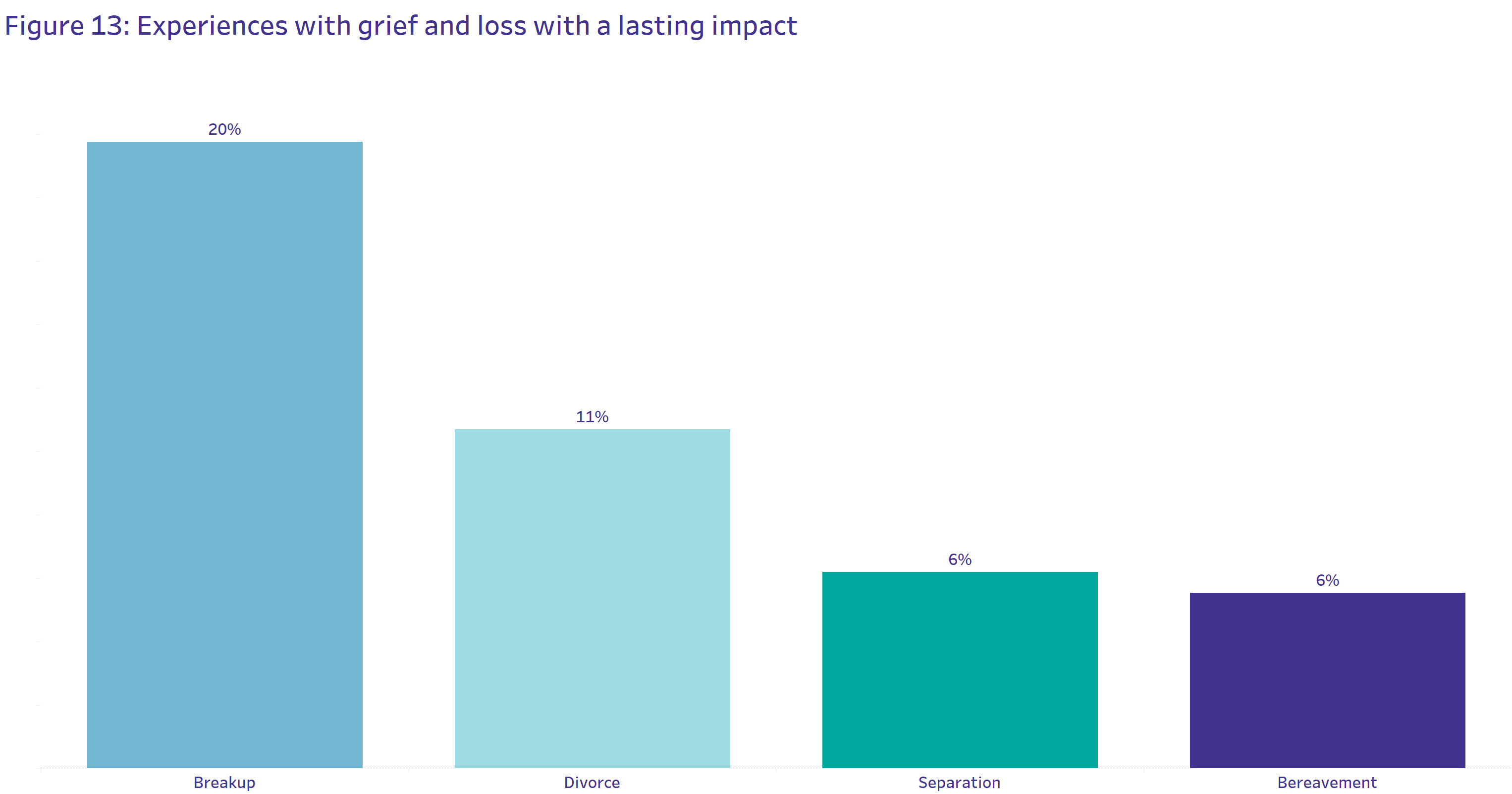

The survey also explored the concepts of grief and loss in partnered relationships. Just under a third (31.4%) have experienced a break-up, separation, or divorce with a lasting impact. While we acknowledge that relationship breakdown is a normal part of life, such breakdowns also present a variety of risk factors for mental ill-health, violence, and suicidality. 61 Relationships Australia was particularly interested in understanding how the ongoing effects of breakdown continued to affect people across the relationship spectrum.

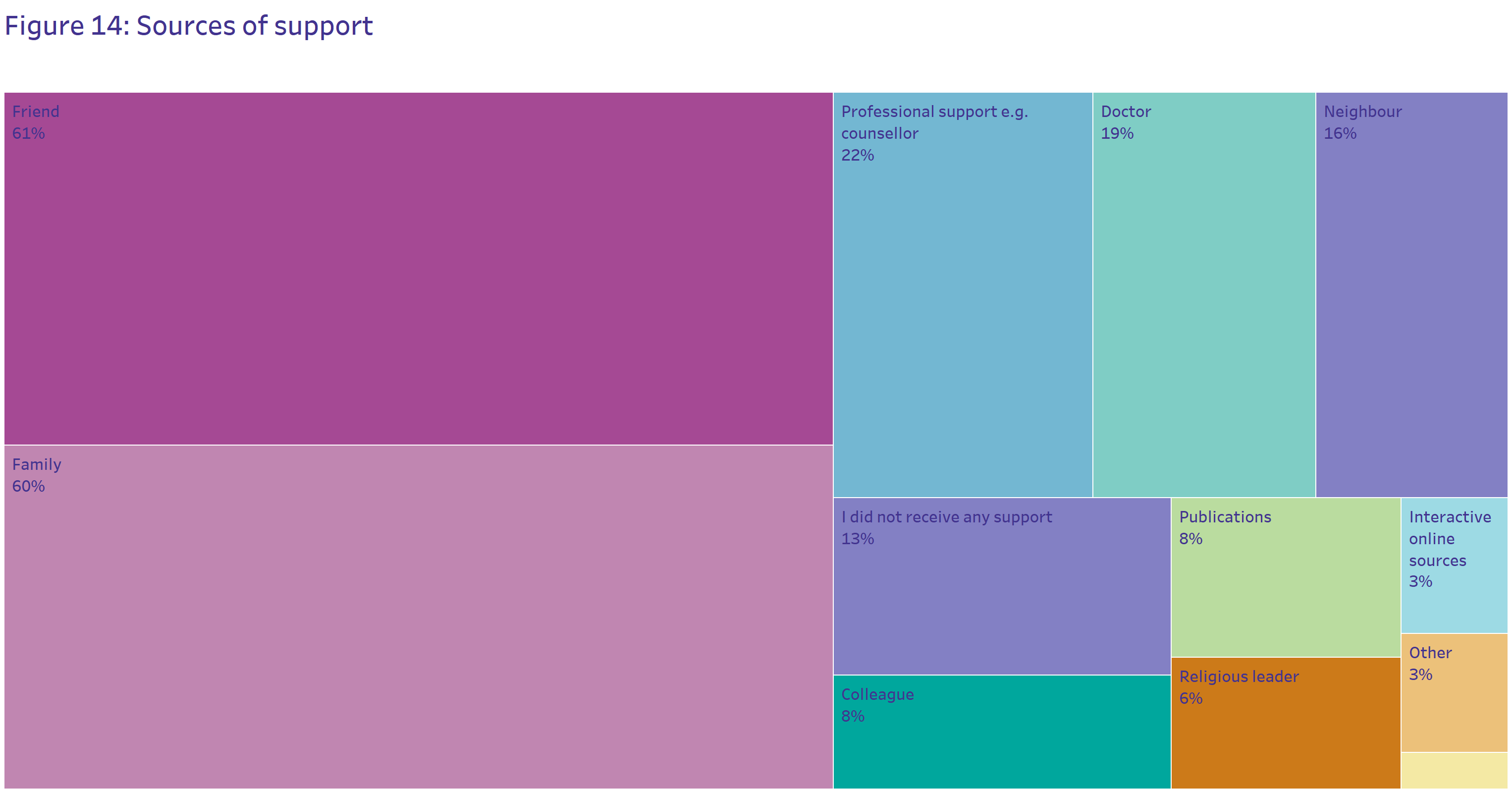

1.1 million Australians (5.5%) have experienced grief from the death of their partner that still affects them today. Friends (61.5%) and family (60%) were the greatest source of support following the loss. 12.6% of people received no valuable support following the death of their partner. People who received support from multiple sources post-bereavement were less socially lonely and their self-rated mental health over the last six months was better than those who did not.

The lasting effects of relationship breakdown and responding to relationship breakdown

Following relationship breakdown, many stated they had trust issues, reduced self-esteem, struggled with their mental health, felt regret, guilt and stress or just a general sense of loss. Many also stated they had an enormous sense of freedom, renewed sense of purpose and new outlook on life following the relationship breakdown. Relationships Australia will be releasing a special report on the qualitative findings from this portion of the survey in 2023.

“I guess it taught me how to love, and how to get over it”– man, 35-44

The effects of inadequate support

Although relationship breakdown and bereavement are common, their effects on people are ongoing, especially if they did not receive adequate support throughout the experience and its aftermath.

People who reported lasting impacts from a relationship breakdown and/or bereavement were 1.5 times lonelier than those who didn’t have these experiences

Our analysis did not find that these experiences could reliably lead people to rate their mental health as poorer.63 However, qualitative responses demonstrated that people’s mental health suffered significantly following these experiences. Additionally, modelling showed that self-rated mental health would improve without these experiences. This suggests that better support during and following these experiences could prevent mental ill-health as a result of relationship breakdown.

For those who had experienced bereavement, finding the motivation/desire to access support was the biggest barrier (46%). Following this, was the isolation they felt after the experience (15%), a factor which could be related to motivation and desire. For those who selected ‘other’, many mentioned the role their religion and pets played. Given the effect grief has on levels of loneliness and mental health, finding ways to motivate and increase people’s desire to gain support to navigate these experiences could mitigate these effects.

Accessing Support

Key points

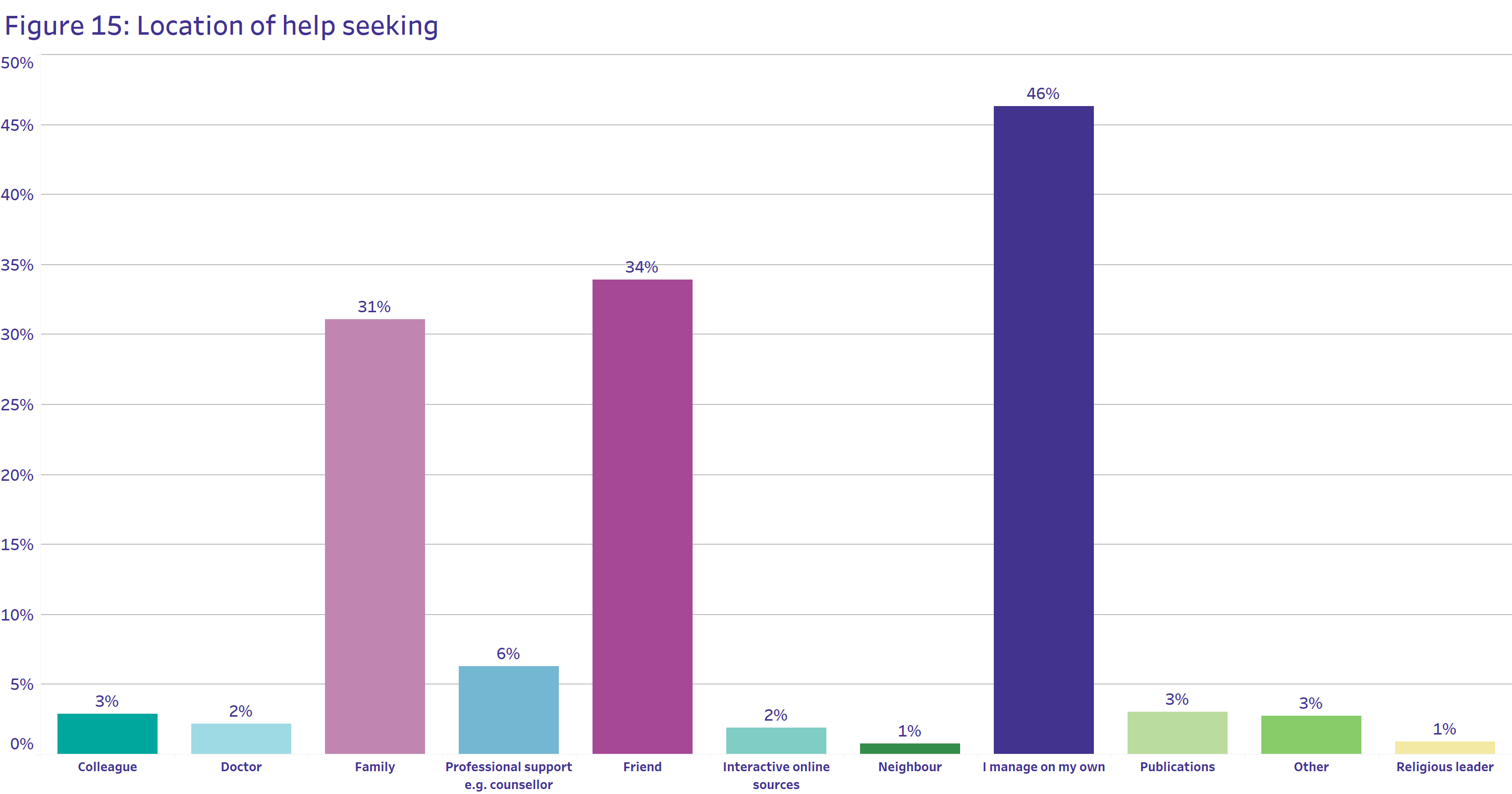

- Australians are unlikely to seek support to manage their relationship issues. Almost half (46.2%) of Australians manage their relationship issues on their own.

- If Australians do seek-support, it’s usually from family and friends, rather than from professionals, publications or online.

- Group-based connections are important for wellbeing. People who had strong group-based connections were more satisfied with life.

- People are more likely to go to their close family for mental health support now than in 2017, suggesting that people feel more comfortable seeking mental health support from their family.

- Men are struggling to connect emotionally and socially. Men scored lower across a variety of measures and were less likely to be relied on for emotional and social support.

- Having a strong and reliable relationship improves subjective wellbeing, reduces loneliness and enhances mental health.

Australians have very low rates of help-seeking to address relationship issues

The challenges associated with seeking help for relationship issues are not only limited to those who have experienced bereavement. Accessing support for relationship issues is uncommon.

46.2% of Australians manage their relationship issues on their own

Alternatively, 6.3% said they would seek professional support, such as a counsellor, if they were having troubles with their most important relationship. Notably, people with long-term mental health conditions, disabilities and/or long-term physical health conditions were more likely to seek professional support than the general sample, while carers were less likely than the general sample.

A further 10.8% of people said they don’t have any difficulties in their important relationship. When we asked this group64 about the strategies they use to manage pressures, the most common responses were that they didn’t know, did nothing or didn’t bother anymore (18.4%). Many others said they would ignore the issue. If people did seek support for a relationship issue, it was most likely from friends (33.8%) or family (31%). Our analysis did not find that certain kinds of relationships (familial, friends or partners) were more likely to access support than others.

“It’s best not to bring it up. Just try to ignore it” – Man 65-74 years

“Just ignore it…not worth the chat” – Woman, 45-54 years

“Just ignore…focus on [being] the best of yourself” – Woman, 55-64 years

The importance of group-based connections

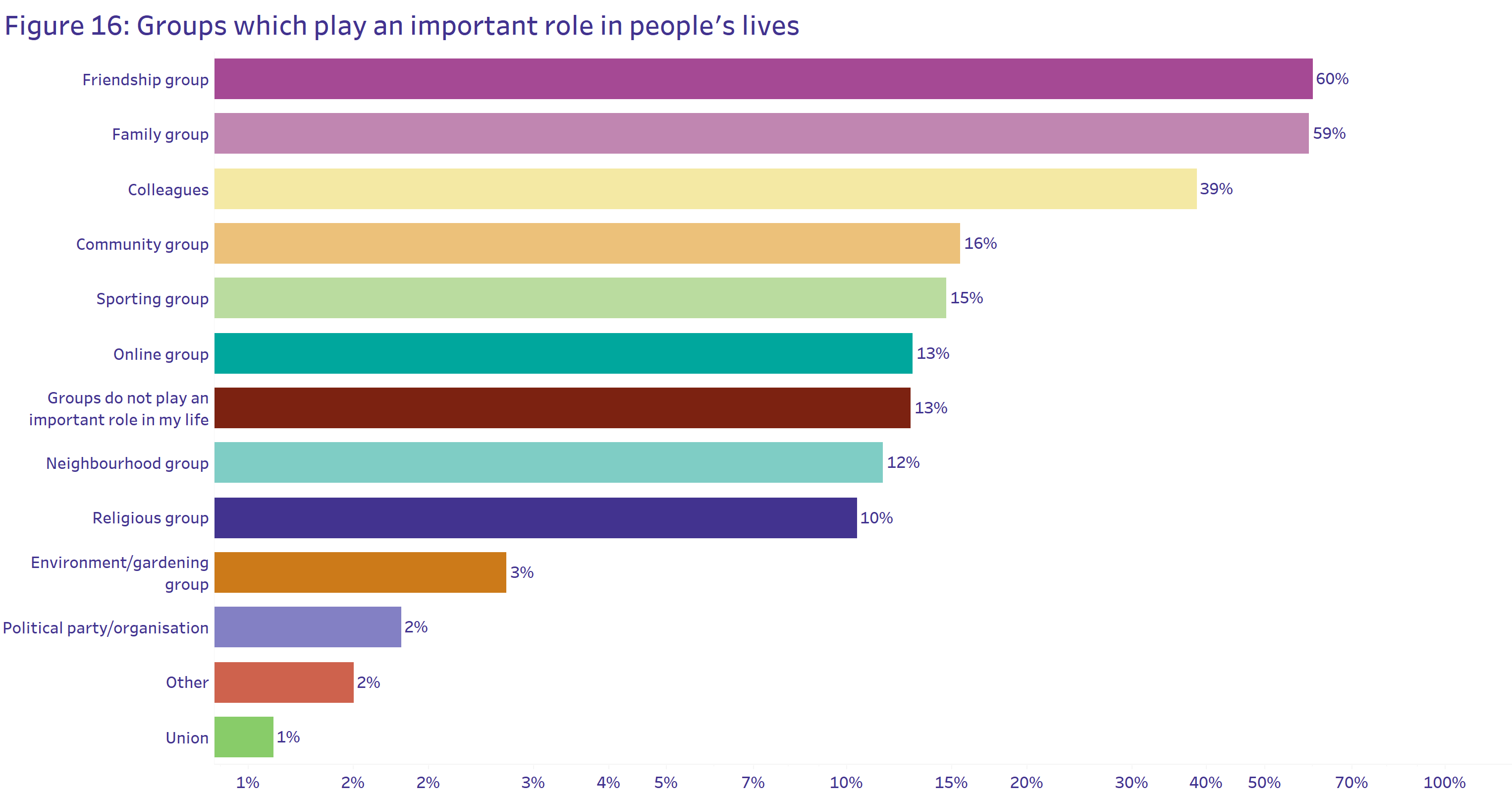

Over 3.1 million (or 15.5%) Australians are involved in a community group

Being part of a group is good for subjective wellbeing. Participants were asked to identify groups which ‘play an important role in their life’. People who identified their family, friendship circles, neighbours, community, religious and sporting groups had higher subjective wellbeing than the population,65 while those who identified online groups (12.9%) as important had lower subjective wellbeing. The strength of people’s identification with these groups also influenced subjective wellbeing. People who thought of themselves as part of the group or felt that the group was part of their identity were more likely to demonstrate subjective wellbeing. However, trusting the thoughts and opinions of the group was not found to be important for subjective wellbeing. This suggests that having a sense of belonging within a group was integral to subjective wellbeing, however maintaining one’s own opinions is important.

7.5% said their colleagues were the most important group of people in their life.

Surprisingly, 15.4% of retirees said that colleagues still played an important role in their life, despite no longer working with them. These findings demonstrate that colleagues play a significant social role in over 1.3 million Australians lives, despite the significant disruptions to people’s work-life during the pandemic. Although being part of a group was good for wellbeing and improved mental health66 it did not have any discernible effect on people’s levels of loneliness.

“[I got over my break-up by] engaging in new activities…talking with friends, family, colleagues.” – woman, 35-44

Where do Australians seek social support?

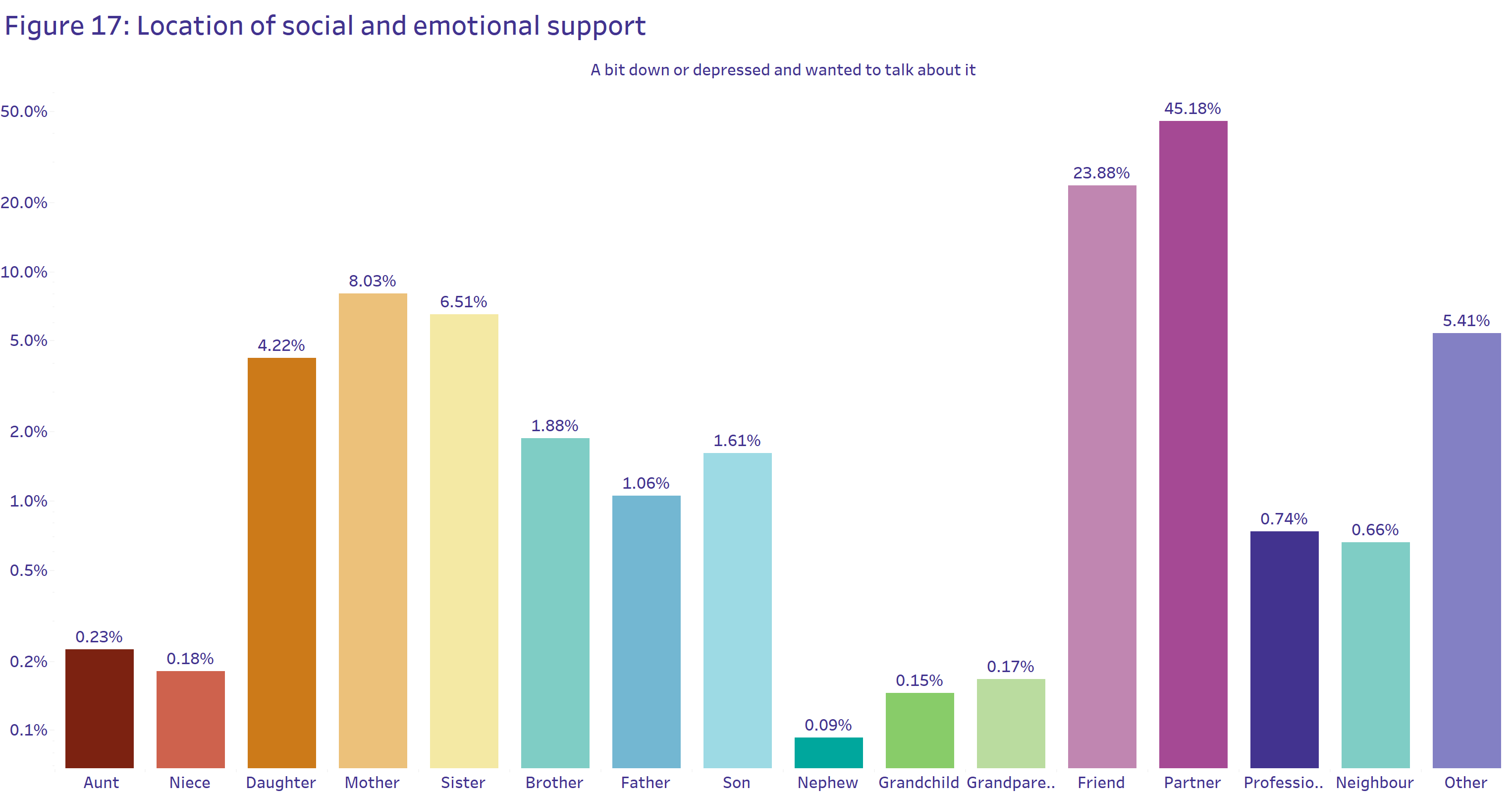

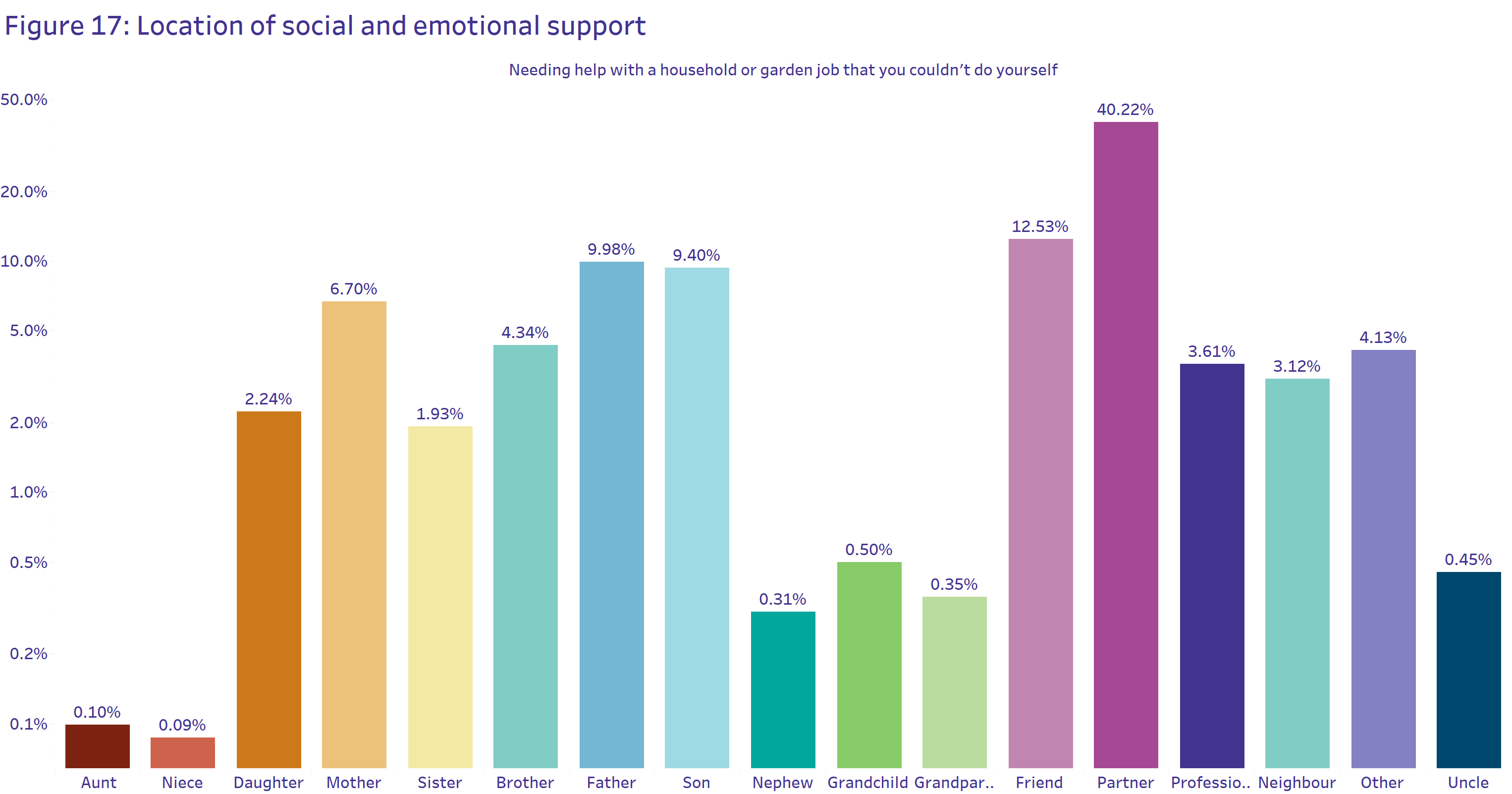

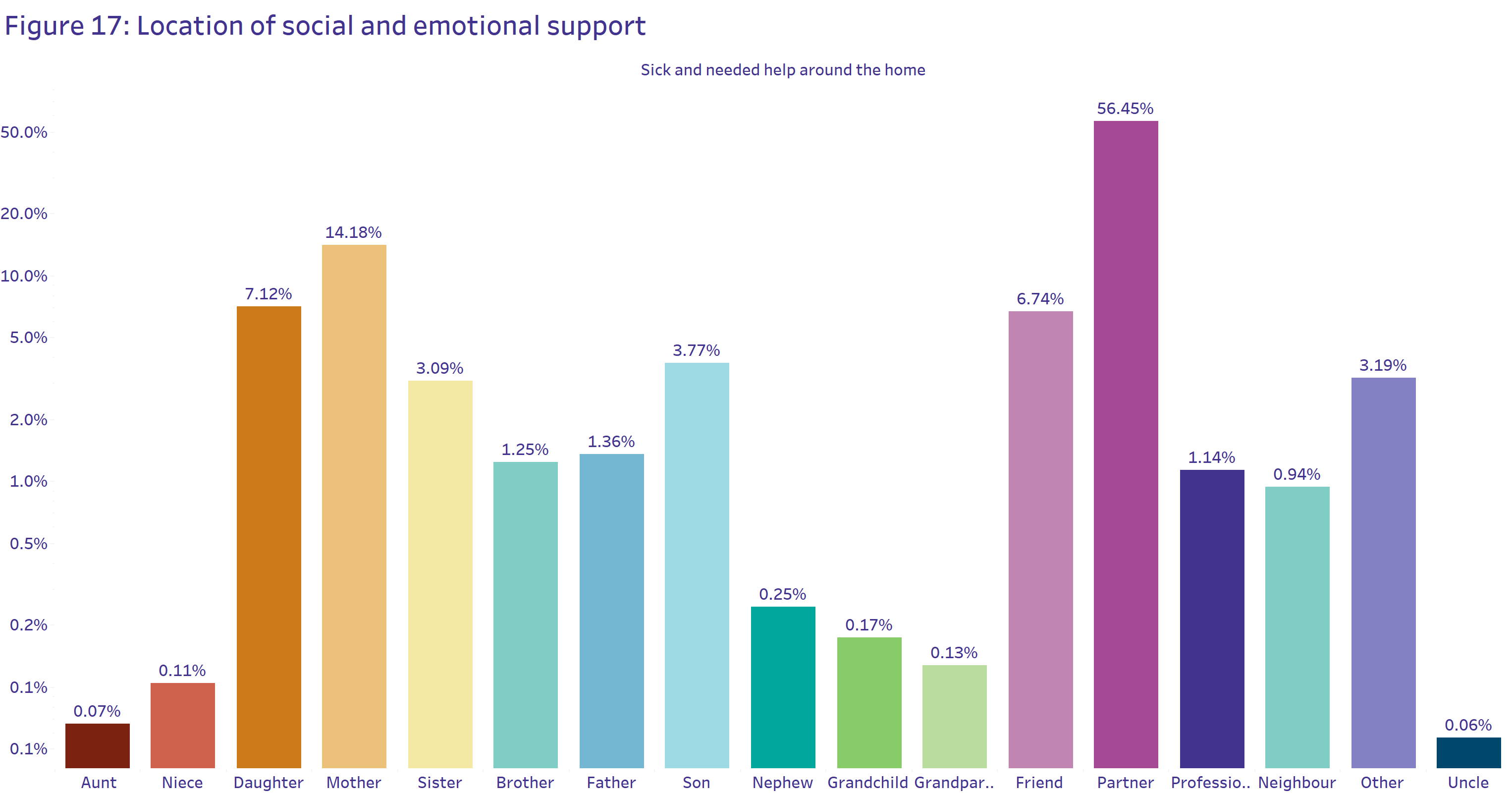

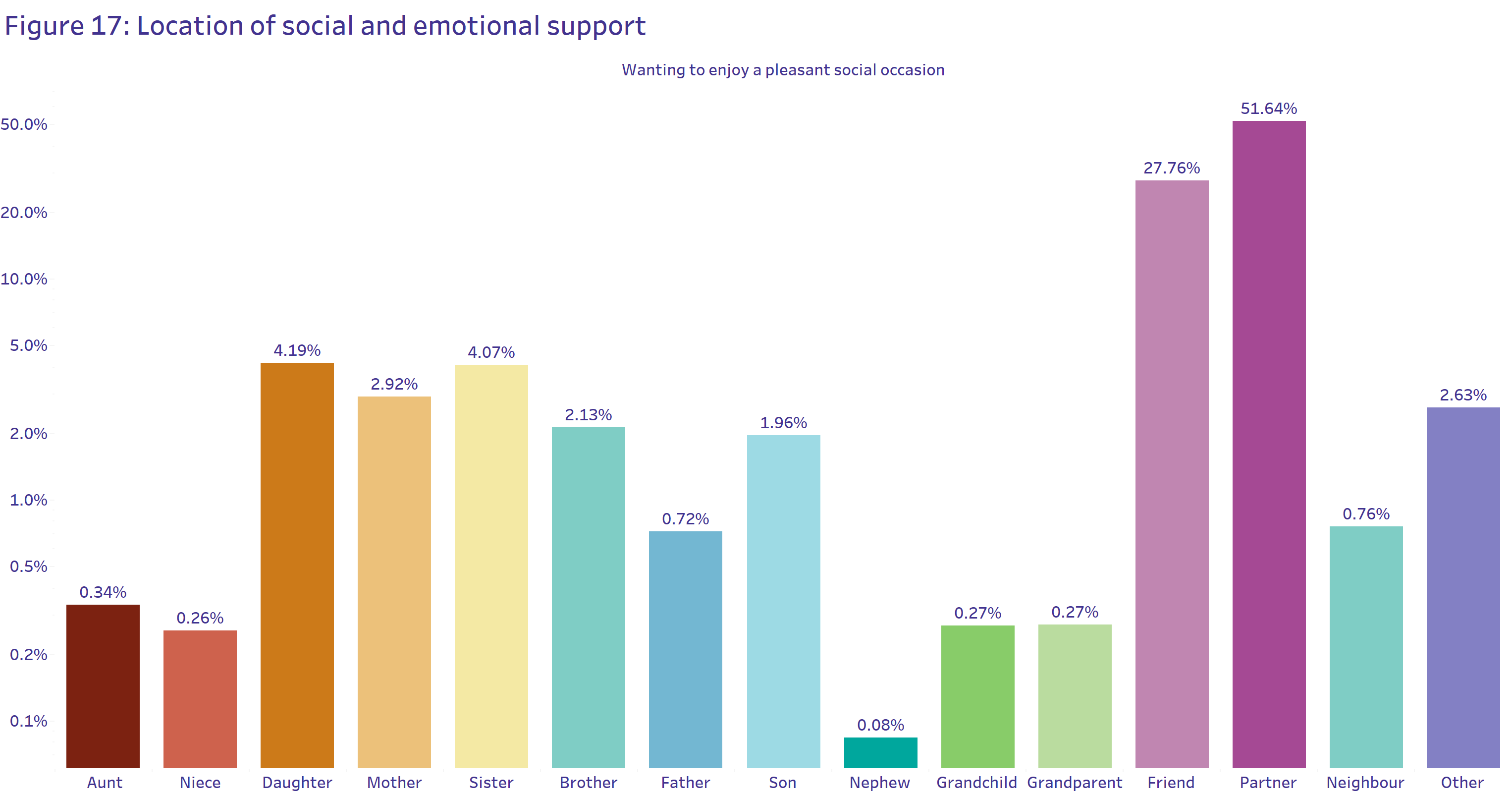

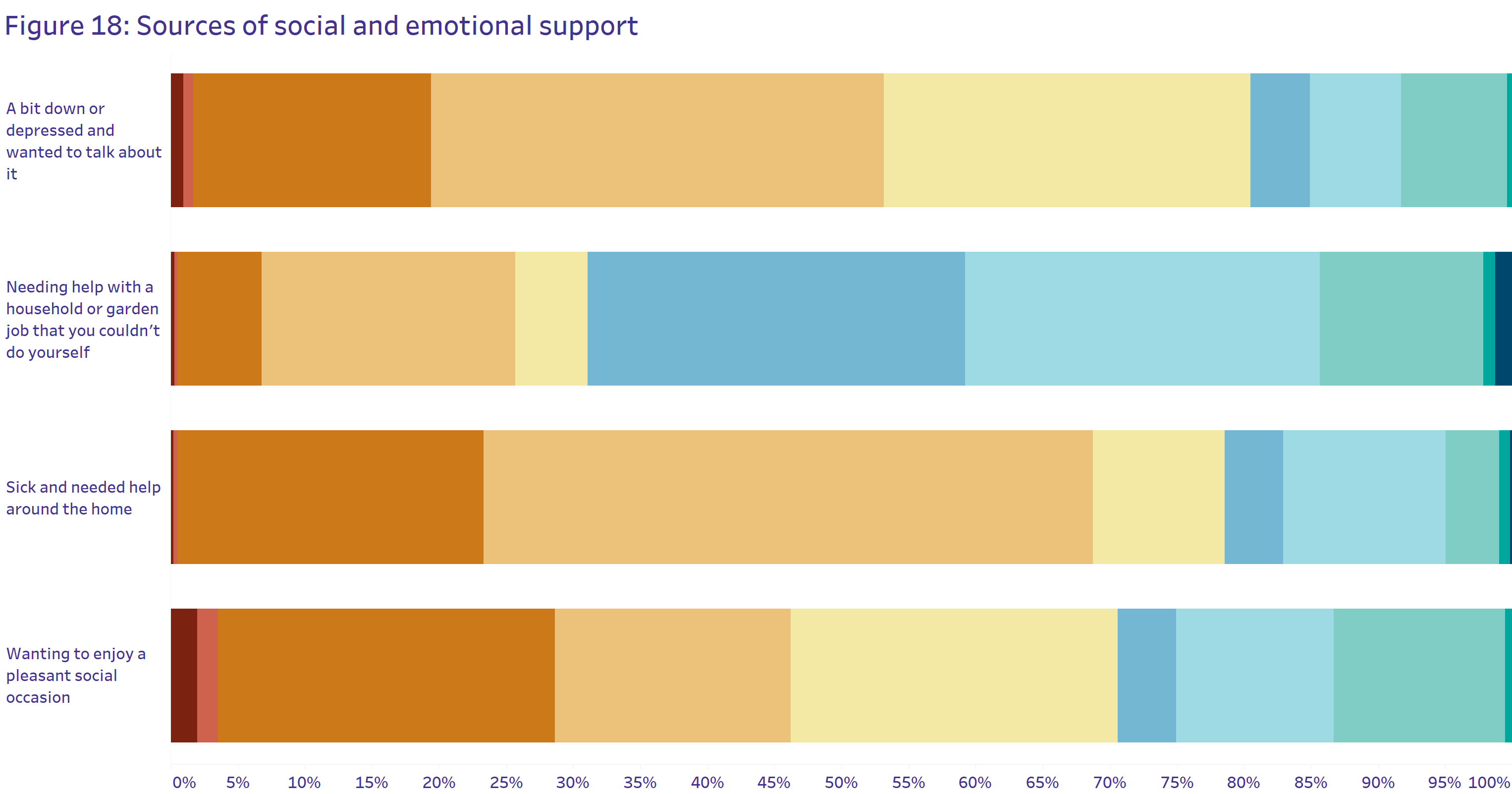

Part of the importance of these group-based connections comes from the support they provide. Our survey re‑administered a selection of survey questions from the 2017 Australian Survey of Social Attitudes. These questions asked people who they would turn to for help in the garden, or if they were sick, if they felt down or depressed and if they wanted to socialise. These questions are a measure of the kinds of support people gain from their social network.

Relationships Australia believes that the pandemic may have affected these responses. The pandemic helped mental health become part of the public lexicon and normalise mental health discussions within some families. It also reduced people’s ability and willingness to socialise with people outside of their closest familial circles, something which appears to have had a lasting effect on people.

“Life has changed dramatically during lockdown. Older people like ourselves are less likely to venture far. We really just don’t bother to make an effort. A familiar problem to those I have discussed the problem with.” – woman, 75+

“Unless I was very sick/badly injured, I’d prefer to manage on my own, even if it was a struggle.” – woman, 35-44

Men are struggling to connect emotionally and socially

Throughout the survey, we found that people were much more likely to identify a woman from their family as a source of emotional and social support. While we did not differentiate the gender of people’s partners,68 figures like fathers and sons were selected much less often than mothers or daughters.

Men were chosen for physical support such as in household or garden tasks but were much less likely to be chosen for social or emotional support. Men were also less likely to be chosen as someone’s most important person in their family, were also more socially and emotionally lonely69, and less likely to agree that they communicated openly about their problems70, and were more likely to manage relationship issues on their own.71

The importance of a strong and reliable relationship

Although Relationships Australia recognises the importance of a variety of strong and reliable relationships, something which has been widely reflected in the social network literature and our own research and reporting, we found a strong correlation across a variety of variables that suggests the importance of also having one, reliable relationship.

People who selected more than one person across a variety of social support measures had a higher than average number of relationship pressures72 compared to those with one form of support. Similarly, people who relied on multiple relationships illustrated lower subjective wellbeing73, worse mental health74 over the past six months and were lonelier.75 Additionally, those who chose their ‘most important person’ in these social support questions scored better across these measures. The pervasiveness of this finding suggests that having a strong relationship which you can rely on for social, emotional, and physical support is extremely important.

Australians low-rate of help-seeking76 poses a risk to these relationships. Compounding pressures in relationships can lead to distress or relationship break-down. Our analysis found that in partnered relationships, breakdown led to increased loneliness, mental health issues and other challenges when creating new relationships. This suggests that not only is it extremely important to have one, reliable relationship, but it is also important to look after this relationship as breakdowns can lead to compounding effects.

These findings highlight the importance of relationship services and other mechanisms which empower people to overcome challenges in their relationships. Given the low rate of professional help-seeking, it is important we equip everyday people with the tools to manage relationship pressures and refer to professional support when necessary. However, we caution against interpreting this finding to mean one relationship can meet all of a person’s relational needs. In fact, Relationships Australia has conducted other research which has found that improving relationships with your wider community significantly improves relationships with family and friends. We interpret these findings to state that while a variety of supportive relationships are important for health, wellbeing and happiness, nurturing your most important relationship to ensure it thrives is also extremely beneficial.

Recommendations

Based on the findings from this research Relationships Australia makes the following recommendations:

1. Continue to fund services and other supports which promote and enable satisfying and strong relationships

99.9% of Australians have at least one important relationship in their life which is not challenged by complete dissatisfaction. With the appropriate supports in place, all relationships can become more satisfying and respectful, reducing risks for relationship breakdowan and improving people’s wellbeing, while reducing risks for loneliness, mental ill-health and suicidality.

2. Include funding for relationship services as part of the national response to issues such as loneliness, mental health and suicidality

Relationship services are often understood as adjacent or complementary to biomedical approaches to loneliness, mental ill-health and suicidality. However, our findings demonstrate that these issues are directly affected by relationship satisfaction. Relationship services should be understood and funded as key responses to these issues.

3. Recognise and acknowledge the impact that the pandemic, successive natural disasters, the rising cost of living and other external pressures, are placing on relationships and do more to relieve these pressures

71.9% of Australians faced relationship pressures in the last six months. While relationship pressures are a regular part of relationships, findings show that they are associated with reduced relationship satisfaction, lower levels of subjective wellbeing and higher levels of loneliness.

4. Recognise that some groups are disproportionately affected by relationship pressures, reducing wellbeing, relationship satisfaction and ultimately contributing to relationship breakdown

Young people, those with long-term mental and physical ill-health, people with disability, carers and LGBTQIA+ communities were shown to be disproportionately affected by relationship pressures. We must do more to understand why this is the case and provide opportunities for these groups to determine what supports would effectively support them through these challenges.

5. Address growing rates of loneliness, especially social loneliness

28% of Australians are experiencing social loneliness. More must be done to address the growing rates of loneliness in Australia. Loneliness is a complex issue that requires a multi-faceted solution. Relationships Australia recommends that a crucial first step is to invest funding in primary responses which address loneliness at the population-level.

6. Fund more research to explore the role age plays on relationships

Our findings tell a unique story about ageing and relationships. Throughout this study, we found that older people had greater relationship satisfaction and wellbeing, reduced loneliness and less relationship pressures. Yet older Australians were also more likely to say they didn’t feel safe disagreeing with their most important person. More must be done to understand how age and relationships affect wellbeing and safety.

7. Empower Australians to create meaningful relationships outside of the partner dynamic

People who chose their partner as their most important person had greater relationship satisfaction and significantly lower levels of emotional loneliness than the population. Australians who are not partnered need more support to ensure that their relationships are as fulfilling as those in partnered relationships.

8. Support boys and men to build respectful relationships and create stronger connections with those around them

Throughout the survey, men were less likely to be identified as close family members, had less satisfying relationships, were less likely to provide emotional and social support to their family members, were lonelier than the general sample, were less likely to agree that they communicated openly about their problems and were more likely to manage relationship issues on their own. Relationships Australia believes there must be more done to understand gendered differences in the experience of relationships. This includes conducting research to explore how these differences relate to phenomena such as masculinity and family violence and developing and providing awareness and education campaigns, combined with tailored supports to enable men to create more fulfilling connections.

9. Continue to fund relationship services and other supports to enable people to navigate relationship challenges in productive, respectful and safe ways

All relationships face challenges; people need support to navigate disagreements and relationship breakdown safely to ensure that the effects of this experience do not harm future relationships, or contribute to loneliness or mental ill-health.

10. Encourage help-seeking and equip Australians to support one another through their relationship struggles

Australians are unlikely to seek professional support for relationship issues, yet relationship breakdown increases loneliness, reduces relationship satisfaction and leads to issues in other relationships. Australians need encouragement to access support earlier and more often. This requires more effort to upskill the community to respond to relationship issues with confidence, given friends and family are people’s most common source of support. It may also include providing relatonship education through other channels such as media, education and workplaces. Additionally, people must be taught how to refer to expert help when needed.

Closing Comments

There is no right way to ‘do’ relationships. Some relationships come easily, while others must be constantly renegotiated and explored. Relationships change throughout the lifetime, especially as other social realities shift. This report has demonstrated the integral role relationships play on our health, wellbeing and happiness. It has also explored how pressures challenge relationships, affecting some sub-populations more than others. It has highlighted the need for supports which help all Australians nurture their relationships, to provide everyone with the opportunity to create respectful, enduring and fulfulling connections throughout the lifetime.

Relationships Australia believes that all people deserve to have respectful, positive, and fulfilling relationships. The findings from this research will be used to support our service provision and advocacy efforts to achieve this goal. We look forward to producing more leading research in the future.

Suggested Citation

Relationships Australia (2022).Relationship Indicators 2022. ‘Full Report’. https://www.relationships.org.au/relationship-indicators/.