There is no single national or internationally agreed definition of family or domestic violence. Historically, commonly held views have been more likely to centre on the physical dimensions of violence. One such example is the framework used by the Australia Bureau of Statistics (ABS), where the definition of partner violence is restricted to actions that constitute offences under State and Territory criminal law:

Introduction

There is no single national or internationally agreed definition of family or domestic violence. Historically, commonly held views have been more likely to centre on the physical dimensions of violence. One such example is the framework used by the Australia Bureau of Statistics (ABS), where the definition of partner violence is restricted to actions that constitute offences under State and Territory criminal law:

“Violence is defined as any incident involving the occurrence, attempt or threat of either physical or sexual assault experienced by a person since the age of 15. Physical violence includes physical assault and/or physical threat. Sexual violence includes sexual assault and/or sexual threat”[1]

Contemporary definitions are more likely to capture a wider range of intimidating or controlling behaviours. For example, the Family Law Act 1975 now recognises a broad range of behaviours, including:

“Violent, threatening or other behaviour by a person that coerces or controls a member of the person’s family (the family member), or causes the family member to be fearful.” (Section 4AB)

This broad definition covers physical and sexual assault; economic abuse; deprivation of liberty; harm to animals and property; threats, taunts and stalking; isolation of a family member from friends, family and culture; and exposure of children to violence. In 2012, the ABS expanded their definition include emotional abuse in light of changes to the Family Law Act; however, ABS statistics are likely to under-report the true rate of domestic violence in the community owing to the narrower definition and the difficulty in collecting information on intimate partner violence due to stigma, shame, economic dependence of the victim on the perpetrator, and safety concerns.

Research suggests that a community’s perception of domestic violence not only has a direct impact on reporting, but also affects help-seeking, service provision, and ultimately outcomes for those impacted by domestic violence. The focus of Relationships Australia’s January survey was to find out whether visitors to our website consider a broad range of behaviours to be acts of domestic violence.

[1] Personal Safety Survey, 2012

Previous research finds that…

- Around one in five Australian women and one in twenty Australian men have experienced violence at the hands of an intimate partner (ABS, 2013).

- Between 2005 and 2012 there was no statistically significant change in the proportion of women and men who reported experiencing partner violence (ABS, 2013).

- Around 65% of men and women who have experienced current partner violence have experienced more than one incident; with women who have experienced violence by a previous partner more likely than men to have experienced more than one incident (73% compared with 51%; ABS, 2013).

- Around half of men and one-quarter of women who have experienced current partner violence have never told anyone about the violence (ABS, 2013).

- In 2011-12, three quarters of intimate partner homicide victims were women (AIC, 2015).

- In 2012 an estimated 25% of all women aged 18 years and over and 14% of all men aged 18 years and over had experienced emotional abuse by an intimate partner since the age of 15 (ABS, 2013).

- Between 40 and 60% of families who present with partner violence also report child abuse.

- In a 2014 Australian study, acts of physical abuse, sexual assault and verbal threats towards one’s partner or child were identified as family or domestic violence by over 96% of respondents. Only 64% of respondents to this study recognised other common attempts to establish power and control over a partner or family member as domestic violence. These forms of control include monitoring a partners’ communication or extreme financial restrictions (Anglicare WA, 2014).

Survey Results Analysis

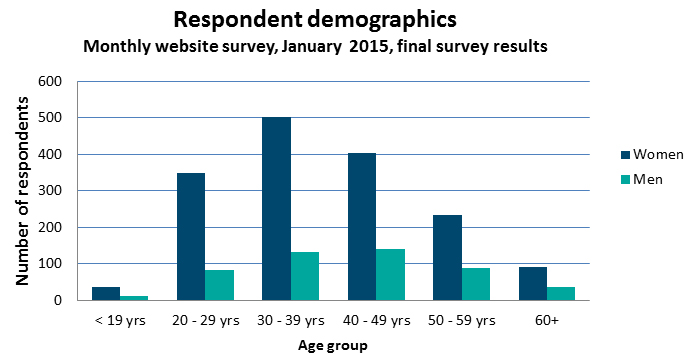

More than 2,100 people responded to the Relationships Australia online survey in January. Around three-quarters of survey respondents identified as female, with more females than males responding in every age group (see figure below). More than 90 per cent of survey respondents were aged between 20‑59 years, while almost 43 per cent of respondents comprised women aged between 30-49 years (inclusive).

As for previous surveys, the demographic profile of survey respondents remains consistent with our experience of the groups of people that would be accessing the Relationships Australia website.

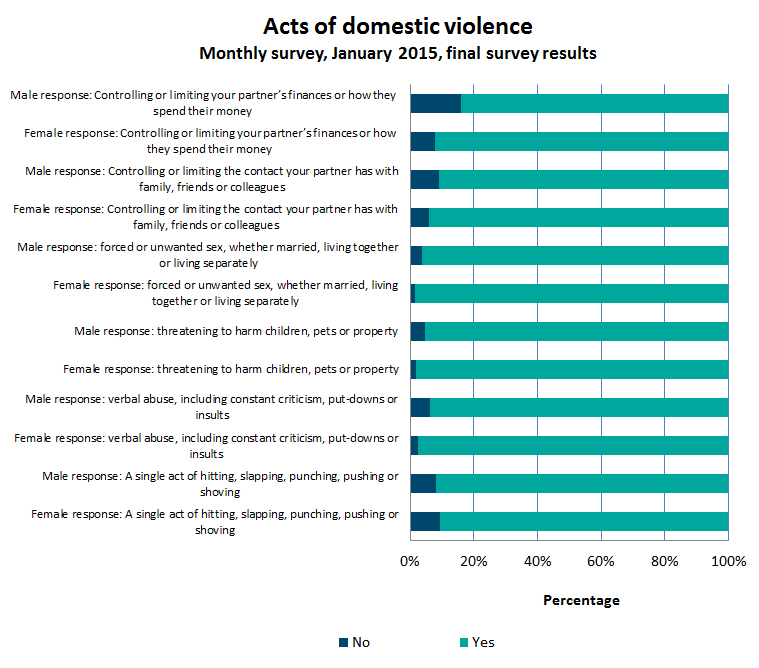

There was a high degree of agreement to the survey questions, with 84-98 per cent of respondents agreeing that they considered the six identified behaviours to be acts of domestic violence. However, in five of the six questions, women were more likely to indicate that they thought the behaviour was an act of domestic violence than men (see figure below).

Just over 90 per cent of men and women agreed that a single act of hitting, slapping, punching, pushing or shoving was domestic violence, while more women (94%) than men (91%) thought that controlling or limiting the contact your partner has with family, friends or colleagues was domestic violence.

Almost all women respondents (98%) reported that they considered verbal abuse, threatening to harm children, pets or property, and forced or unwanted sex to be acts of domestic violence. Men also reported high levels of agreement to these three questions (94-96%), but at lower rates than women.

When asked whether controlling or limiting your partner’s finances or how they spend their money was an act of domestic violence, men and women were the least likely to agree. While around 92% of women though financial abuse was domestic violence, only 84% of men agreed, the lowest level of agreement recorded for the six survey questions.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2013). Personal Safety, Australia, 2012, Cat no. 4906.0. Canberra.

Australian Institute of Criminology. (2015). Homicide in Australia: 2010–11 to 2011–12: National Homicide Monitoring Program report.

Anglicare WA. (2014). Community Perceptions Report, Family and Domestic Violence, 2014.

National Council to Reduce Violence against Women and Children. (2009). Background paper to Time for Action: The National Council’s plan to reduce violence against women and children, 2009–2021, Canberra.