Introduction

Evidence consistently shows that same-sex attracted people experience high levels of discrimination, including in the workplace, schools and hospitals. Discrimination may result in conflicted family and other social relationships and diminished emotional and practical support, despite the support of family, friends and, to a lesser extent, professionals having been shown to lessen the destructive impacts of homophobia (Hillier et. al 2005, Green, 2004; Greenan & Tunnell, 2003).

The term ‘minority stress’ captures the negative effects associated with the adverse social conditions experienced by members of a stigmatised social group (DiPlacido, 1998). Minority stress increases vulnerability to mental and physical illness. This is not as a result of identifying as gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender per se, rather the associated interpersonal difficulties that arise from stigma and non-acceptance from the general community (Psychologists for Marriage Equality, 2012).

Same-sex attracted people are more likely to experience higher levels of abuse, violence and assault. There have also been strong links identified between legal bans on same-sex marriage and homophobic abuse, and higher psychiatric morbidity, feeling unsafe, excessive drug use, self-harm and suicide attempts, and decreased life satisfaction for same-sex attracted people (Barlow et al. 2012).

Same-sex couples also often face intense scrutiny over their capabilities as parents, based solely on their sexual orientation. These beliefs are often not based on personal experience and evidence, but on culturally transmitted myths and stereotypes (Psychologists for Marriage Equality, 1998).

The focus of November’s online survey was to ascertain the views of visitors to the Relationships Australia website on marriage equality.

Previous research finds that…

- The more same-sex attracted people perceive others devalue their relationship, relative to heterosexual relationship, the lower their reported psychological well-being

- Conversely, the more same-sex attracted people feel their relationships are valued in the same ways as opposite-sex relationships, the greater their overall sense of wellbeing

- 15% of male same-sex couples and 25% of female same-sex couples are raising children

Results

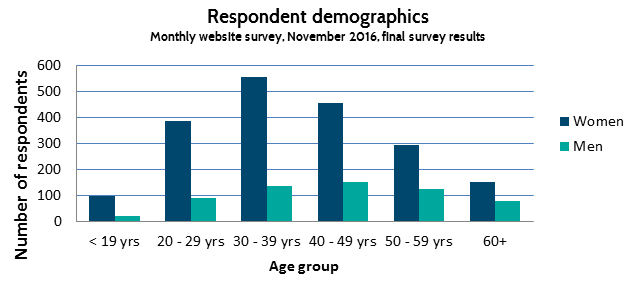

More than 2,650 people responded to the Relationships Australia online survey in November 2016. Around three-quarters of survey respondents (76%) identified as female, with more females than males responding in every age group (see figure 1 below). More than eighty-five per cent of survey respondents were aged between 20‑59 years, and almost 40 per cent of respondents comprised women aged between 30-49 years (inclusive).

As for previous surveys, the demographic profile of survey respondents remains consistent with our experience of the groups of people that would be accessing the Relationships Australia website.

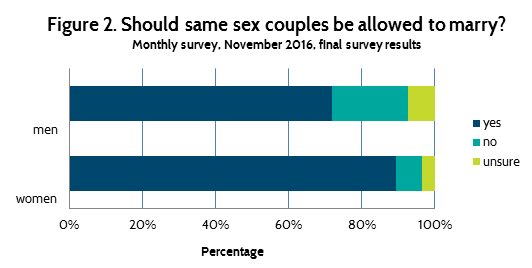

There were significant differences in the reports of men and women when they were asked about marriage equality. Almost 90 per cent (89%) of women and 72 per cent of men reported that they though same‑sex couples should be allowed to marry (figure 2). More than 20 per cent of men and 7 per cent of women thought same‑sex couples should not be allowed to marry.

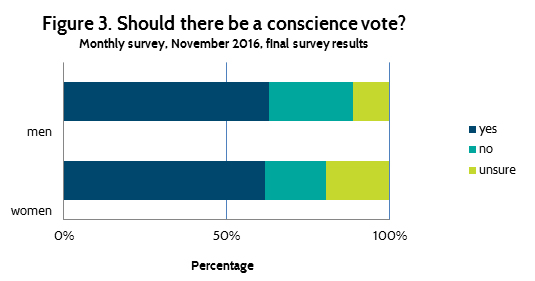

Survey respondents were more likely to express uncertainty when asked whether there should be a conscience vote or plebiscite/referendum on the issue of same-sex marriage. More than 60 per cent of men and women indicated that they supported a conscience vote in parliament on the issue of same-sex marriage, while more than 20 per cent of women and 11 per cent of men were unsure (figure 3).

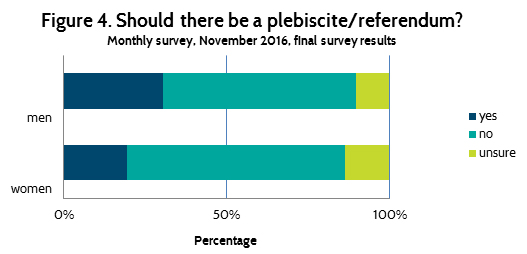

The majority of survey respondents did not support a plebiscite or referendum on the issue of same-sex marriage (figure 4).

The majority of survey respondents also reported that they thought same-sex marriage was inevitable (women – 85%, men – 75%).

References

Barlow, F, K, Dane, S, K, Techakesari, P & Stork-Brett, K, 2012, The psychology of same-sex marriage opposition. School of Psychology. The University of Qld.

DiPlacido, J, 1998, Minority stress among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals: A consequence of heterosexism, homophobia, and stigmatization. In G. M. Herek (Ed.), Stigma and sexual orientation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Green, R, J, 2004, Risk and resilience in lesbian and gay couples: comment on Solomon et al., J. Fam. Psyc, 18(2), 290–292.

Greenan, D, E and Tunnell, G, 2003, Couple therapy with gay men. New York: Guildford Press.

Hillier, L, Turner, A and Mitchell, A, 2005, Writing themselves in again: 6 years on, the 2nd national report on the sexuality, health & well-being of same sex attracted young people in Australia, mon. series no. 50, Melb: Australian Centre for Sex, Health and Society.

Psychologists for Marriage Equality, 2012, Submission to the Senate Inquiry into the Marriage Equality Amendment Bill 2012 and the Marriage Amendment Bill 2012 viewed at http://www.australianmarriageequality.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/7.Pyschs-for-equality-Senate-submission.pdf

See also: http://www.australianmarriageequality.org/faqs/3-the-other-benefits-that-come-with-marriage/