Introduction

This report presents the results of the third survey in a series that examines the levels of social isolation and loneliness for people accessing the Relationships Australia website.

We have previously discussed the research evidence that clearly establishes the importance of social connection to overall wellbeing. The negative effects of social isolation were first identified in the 1970s, including by the World Health Organisation in 1979 and in a range of studies since this time, loneliness has been associated with a range of poor mental, physical and socio‑economic outcomes, including low self-esteem, suicide, depression, heart disease and poor physical health.

While there is no clear understanding of how social isolation impacts on health, we know that the existence of this relationship has important implications for both policy and practice. The work of Brummett (2001), for example, established the importance of ensuring that individuals have meaningful social ties with at least one or a few other individuals, and this is especially true for people whose health is already compromised by significant morbidity. It does not seem that any particular type of relationship is crucial and as long as a person has regular interaction with a spouse, extended family or friends, the risk of social isolation negatively impacting their health is minimised. It also seems that there is little additional health benefit associated with adding extra social connections for well-connected individuals.

This month’s online survey employs the Lubben Social Network Scale, a 6-question instrument designed to gauge social isolation by measuring perceived social support received by family and friends (Lubben et al. 2006). The Scale identifies individuals with a score of less than 12 as socially isolated which implies that, on average, a person can identify fewer than two individuals for each of the six aspects of the social networks assessed. Furthermore, those people with scores of less than 6 on the three-item family subscale are considered to have marginal family ties and those with scores of less than 6 on the three-item friends subscale are considered to have marginal friendship ties.

Previous research finds that…

- Various factors, such as disability and major life events (e.g., loss of spouse) can put older adults at greater risk of experiencing social isolation or loneliness.

- The prevalence rate of social isolation is around 10% to 15% in a number of European studies.

- The level of health risk associated with social isolation has been compared with that of cigarette smoking, obesity and other major biomedical and psychosocial risk factors.

Results

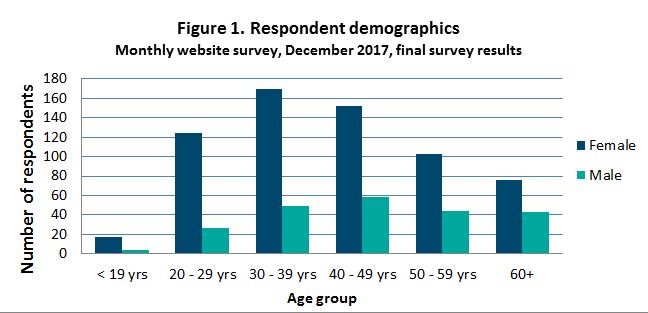

More than 900 people responded to the Relationships Australia online survey in December 2017. Around three-quarters of survey respondents (74%) identified as female, with more females than males responding in every age group (figure 1). Eighty three per cent of survey respondents were aged between 20‑59 years, and more than 50 per cent of respondents comprised women aged between 30-49 years (inclusive).

As for previous surveys, the demographic profile of survey respondents remains consistent with our experience of the groups of people that would be accessing the Relationships Australia website.

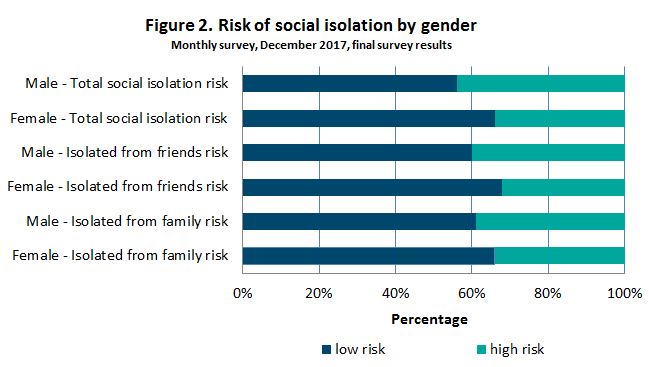

There were significant differences in the reports of male and female survey respondents on the Lubben Social Network Scale and subscales reported at figure 2: total risk of social isolation; risk of isolation from family; and risk of isolation from friends.

The three questions comprising the family subscale included questions relating to how many family members they saw or heard from at least once a month, felt comfortable with talking about private matters and whom they could call on for help. One-third (34%) of female survey respondents and 39 per cent of male survey respondents reported low levels of connection that identified they were at risk of isolation from family.

The three questions comprising the friends subscale asked respondents to report on how many friends they saw or heard from at least once a month, felt comfortable with talking about private matters and whom they could call on for help. One-third (32%) of female survey respondents and 40 per cent of male survey respondents reported low levels of connection that identified they were at risk of isolation from friends.

Overall, the results suggest that 34 per cent of female survey respondents and 44 per cent of male survey respondents are at clinical risk of social isolation. The reports of respondents to December’s monthly online survey suggest levels of social isolation that are substantially greater than those experienced by the broader Australian population.

References

Baker, D (2012). All the lonely people: Loneliness in Australia, 2001-2009, Institute Paper No. 9, June.

Baumeister, RF & Leary, MR (1995). The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachment as a Fundamental Human Motivation. Psychological Bulletin; 117:497–529.

Brummett BH, Barefoot JC, Siegler IC, Clapp-Channing NE, Lytle BL, Bosworth HB, Williams RB Jr, Mark DB (2001). Characteristics of socially isolated patients with coronary artery disease who are at elevated risk for mortality. Psychosom Med 2001;63:267–272.

House, J. S (2001). Social isolation kills, but how and why? Psychosomatic Medicine, 63: 273-274.

Lubben, J, Blozik, E, Gillmann, G, Iliffe, S, von Renteln Kruse, W, Beck, JC, Stuck, AE (2006). Performance of an Abbreviated Version of the Lubben Social Network Scale Among Three European Community-Dwelling Older Adult Populations. The Gerontologist, 46(4): 503–513.

World Health Organization. (1979). Psychogeriatric care in the community: Public health in Europe 10. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.