Introduction

Would you like to be notified when a new survey report is released? Sign up here

Children’s Contact Services provide safe and positive contact arrangements for children whose parents are separated (Children’s Contact Services Guiding Principles Framework for Good Practice 2018, p.3). They operate in two key capacities. Firstly, they enable parents to exchange their children without meeting. During these supervised changeovers, children are left under the supervision of the service staff until the exchange takes place. Children’s Contact Services also offer supervision, where safe visitation takes place with the direct and constant guidance of service staff (Sheehan & Carson, 2006).

Children’s Contact Services occupy a unique position in Australia’s family law system. They provide integral “independent, observational reports on supervised visits” which are useful for the collaboration between Family Law services (FRSA submission, 2019 p.10). Further, Children’s Contact Services seek to emphasise the importance of children’s ongoing relationships with their parents and other significant people in their lives (Children’s Contact Services Guiding Principles Framework for Good Practice, 2018 p.3). Children’s Contact Services are considered integral to realising the children’s right to participation (Article 12 Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989).

The ultimate goal of Children’s Contact Services is to assist, where safe to do so, families to move to self-managed contact (Attorney-General’s Department 2018, p.3). Despite this, research from the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) suggests that only a small number of families move to self-managed arrangements (Commerford & Hunter 2015). Further, AIFS suggests that there is little guidance as to how services should manage this transition for families, with varying expectations of the role Children’s Contact Services should play during this transition. This was reflected by the Attorney-General’s Department, which found that “there are inherent tensions…that place competing demands on CCS’s” (AGD 2018).

The Attorney-General’s Department released an updated Guiding Principles Framework for Good Practice in relation to Children’s Contact Services in 2018. This restates the aims, safety requirements, policies and procedures for good service delivery (2018). Children’s Contact Services can be government funded, full-fee paying (usually established by a NGO with some government funding) or privately owned (ACCA 2019). In the Review of the Family Law System final report released in April of this year, a recommendation was put forward that any organisation offering Children’s Contact Services should be accredited (ALRC Report 135). However, there are long waiting lists for services and funding is currently desperately underfunded. Further, to ensure consistency and stability while preparing for possible reforms, recent funding was limited to organisations who currently deliver family law services (Community Grants 2019).

Given the paucity of research into Children’s Contact Services, Relationships Australia has conducted research with website users to explore the public’s thoughts on the service.

Previous research finds that…

- Children’s Contact Services reduce children’s exposure to marital conflict, which betters enables contact with both parents and enhances children’s wellbeing (Smyth, 2004).

- Sheehan and Carson found that Children’s Contact Services can enable children to explore their relationship goals throughout contact visits (2006).

- Humphreys and Harrison suggest that the level and vigilance of supervision required during contact visits should be determined by the nature of risk factors to the child (2003). Crawford, however, advocates for the ‘within sight and hearing principle’ (2005).

- Commerford and Hunter found that many families who use Children’s Contact Services have complex needs. This can render the goal of self-managed contact unachievable (2015). This was reflected in a Canadian study which found that despite being framed as a ‘stepping stone’, Children’s Contact Services are mostly permanent solutions (Bala, Saini & Spitz, 2016).

- Ongoing studies are currently being conducted across Australia to consider the effectiveness of enhanced models of contact for children (Taplin et al., 2015; Bullen et al., 2016).

Results

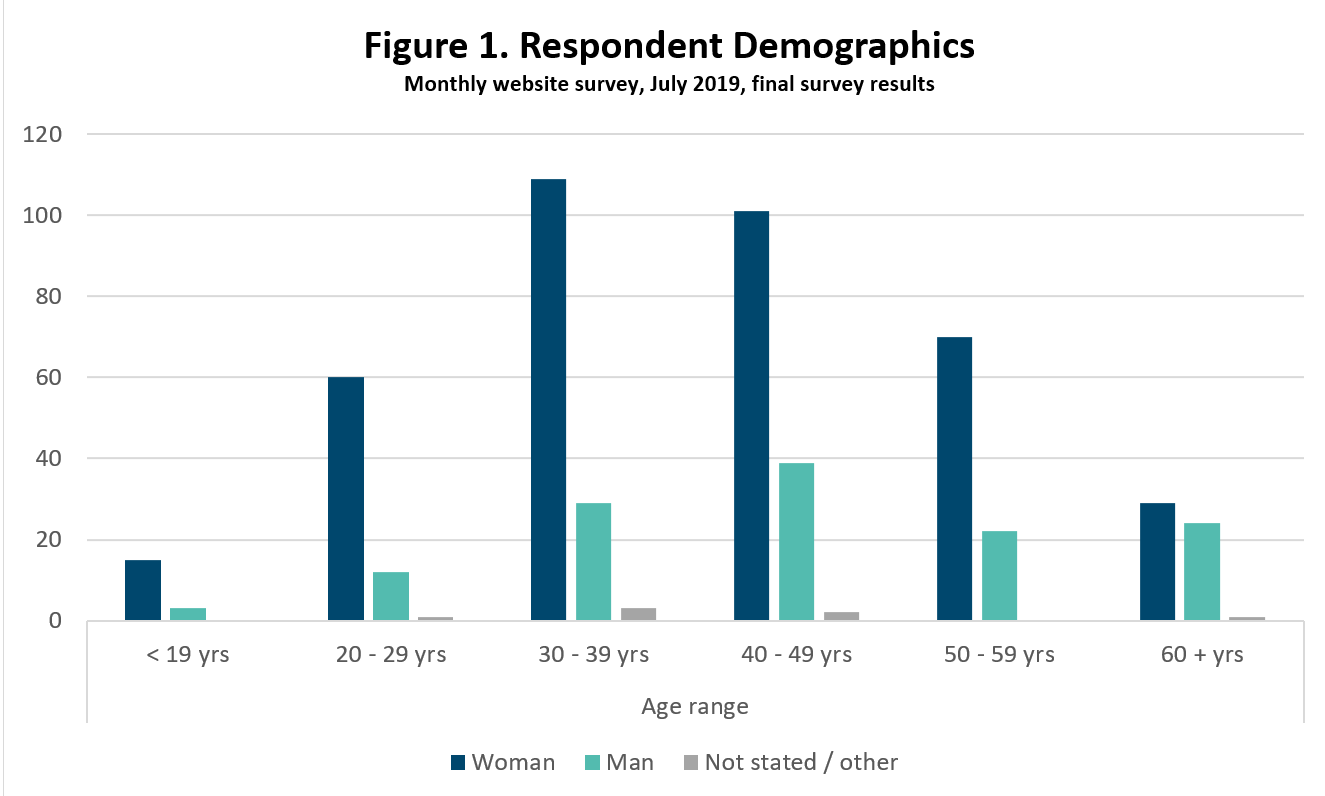

547 people responded to the July 2019 survey on the Relationships Australia website. Seventy‑four percent of these respondents were women and a further twenty-five percent were men, one percent did not state their gender (figure 1). As with past surveys, the majority of respondents were aged 30-49 years (54%). The demographic profile of survey respondents remains consistent with our experience of the groups of people that would be accessing the Relationships Australia website.

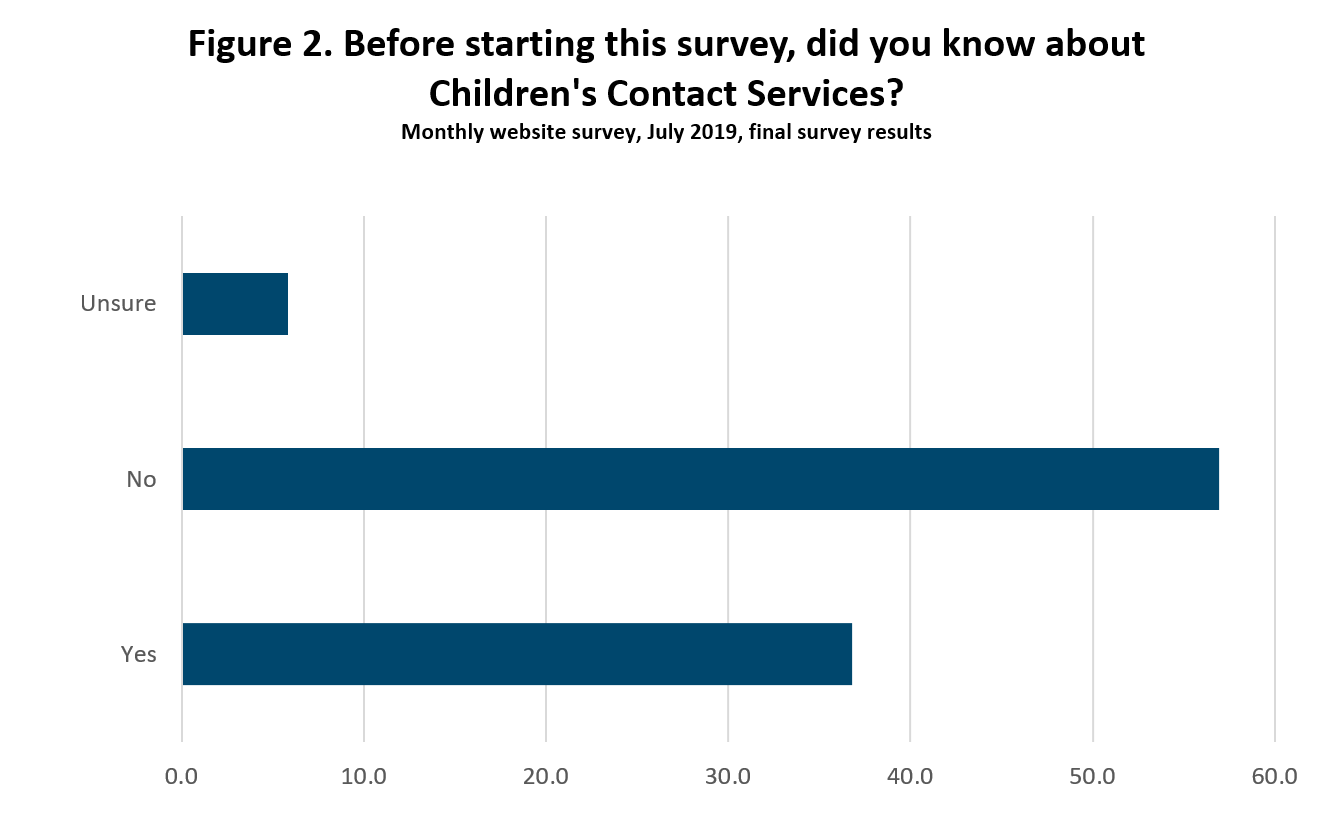

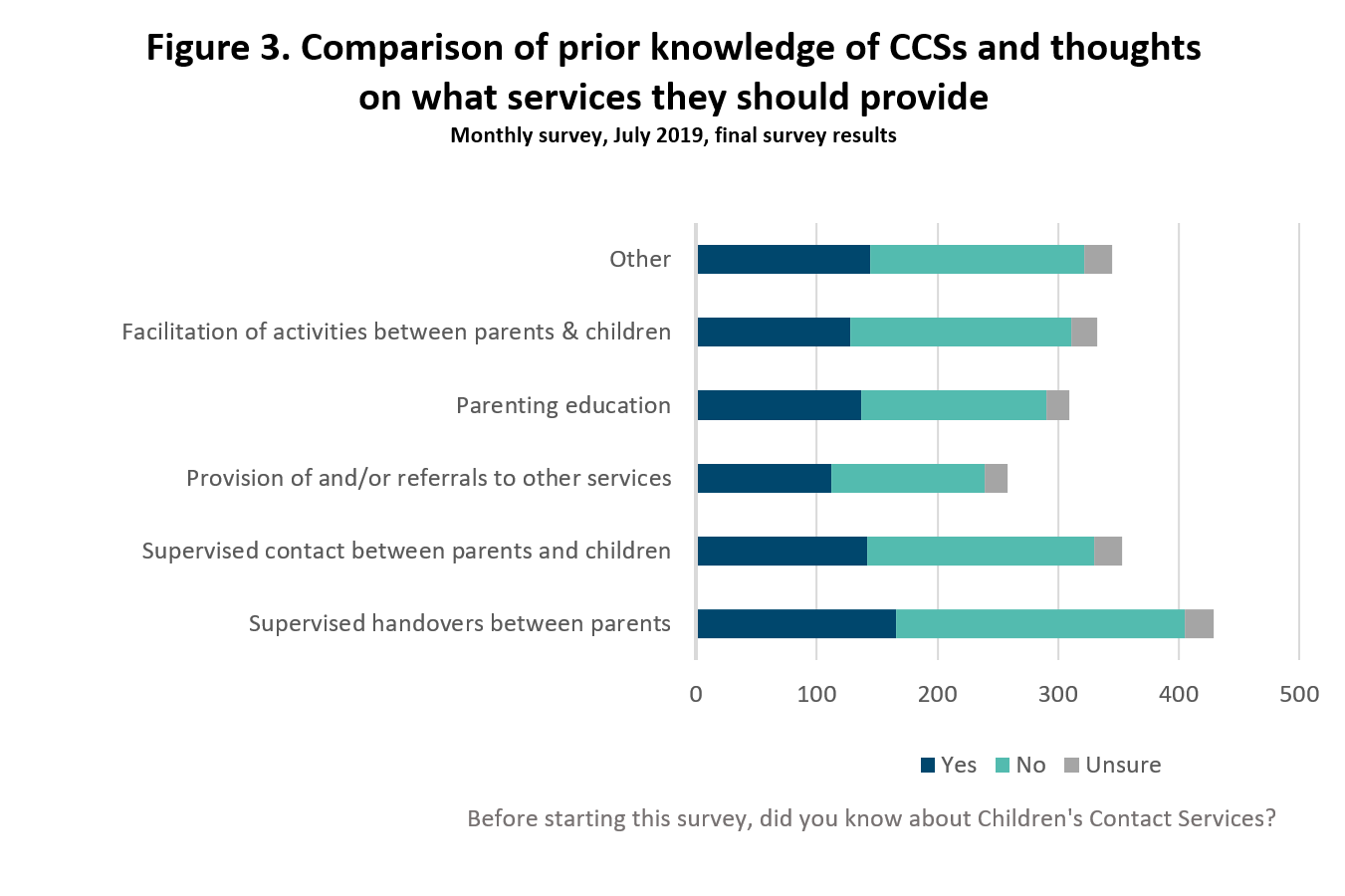

Before starting this survey, fifty-seven percent of survey respondents were unaware of Children’s Contact Services (figure 2). A further six percent were unsure. Despite many being unfamiliar with Children’s Contact Services, prior knowledge of the program had little effect on the types of services respondents felt they should provide (figure 3). In fact, while supervision of handovers received the most support (79%), all services listed were supported by forty-seven percent to sixty-five percent of respondents (figure 3).

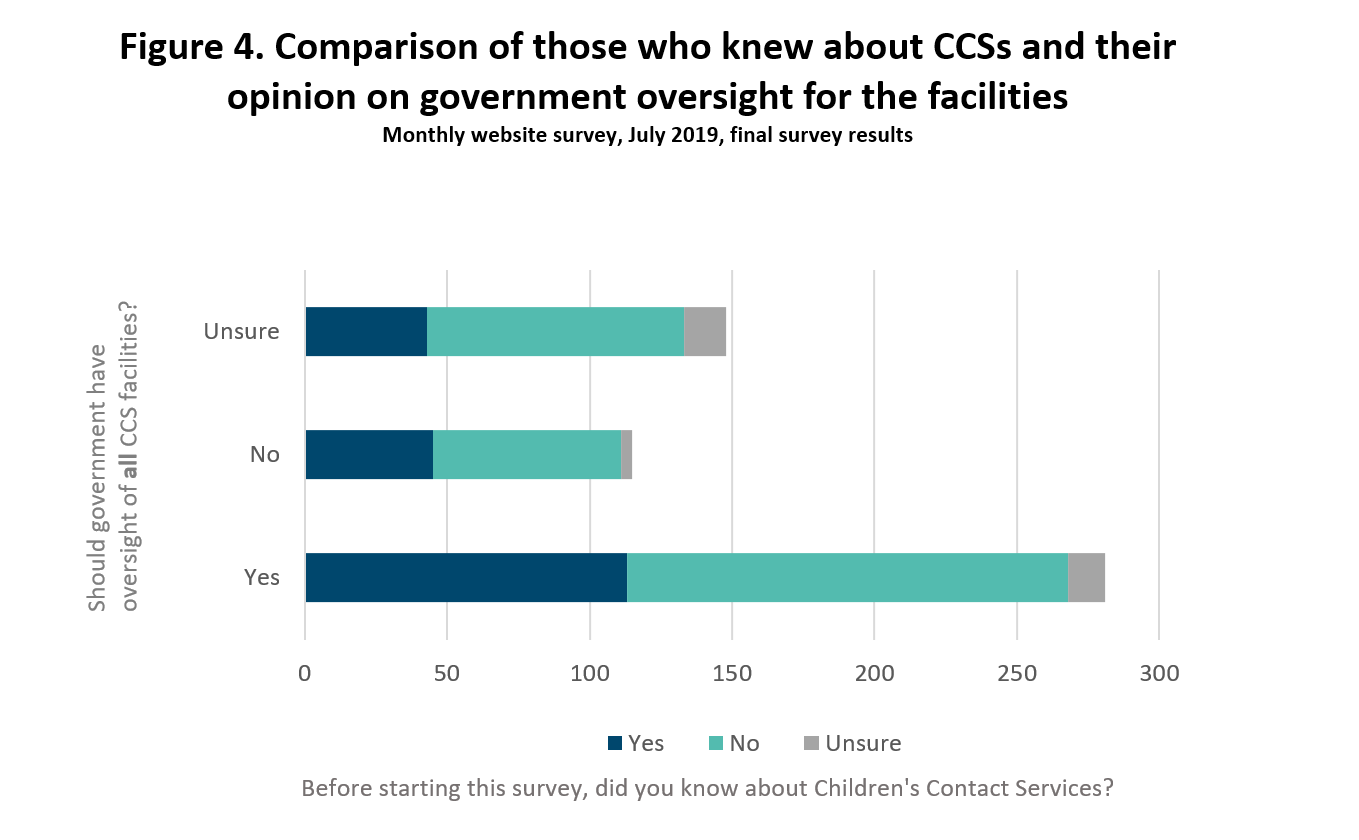

Similarly, figure 4 demonstrates that a respondent’s prior knowledge of Children’s Contact Services had little effect on whether they felt government should have oversight over all facilities. While fifty-two percent felt they should be overseen by the government, forty‑eight percent were either unsure or felt that they should not be supervised. Among these responses, there was an insignificant difference between those who previously knew about CCSs (either by using their services or just a general awareness) and those who did not. This suggests that previous experience with, or knowledge of, Children’s Contact Services has not significantly affected people’s thoughts on their management and service provision.

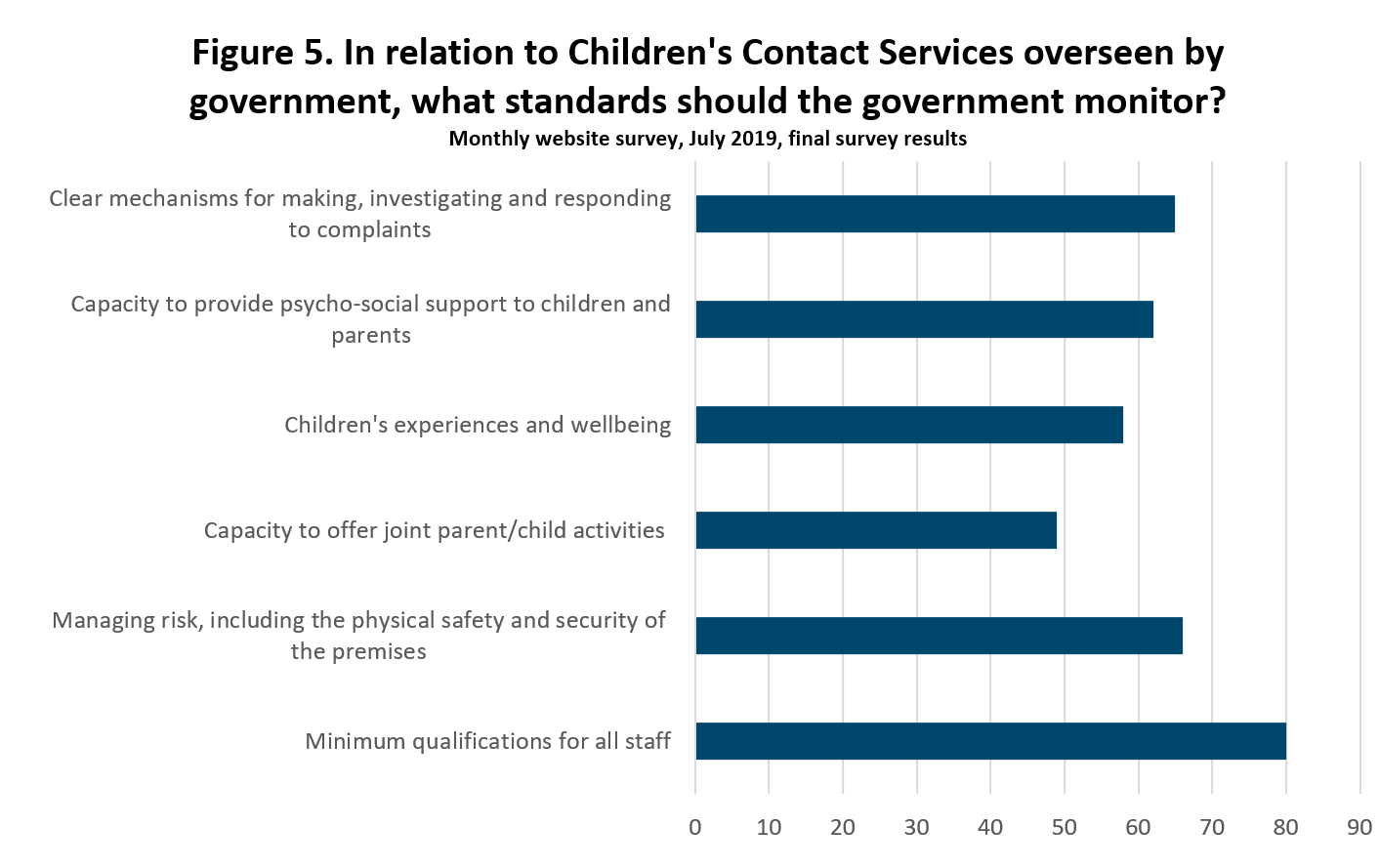

When asked about the standards governments should impose on the Children’s Contact Services that they do oversee, great support was found for establishing minimum qualifications for staff (figure 5). Eighty percent agreed staff should be acquiring minimum qualifications, including training in child development, child protection, psychology or social work, as well as ongoing supervision and professional development. Additionally, providing mental health services, managing risks and security and creating mechanisms for responding to complaints was of high priority for respondents (62%, 66% and 65% respectively) (figure 5).

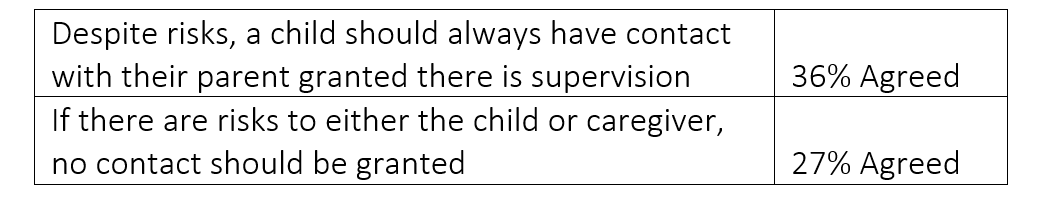

It is widely recognised that contact with both parents is important for a child’s wellbeing and future development, following a family break-up (except in a small number of circumstances). Across several survey questions, it was found that thirty-six percent of respondents recognised this, illustrating that they felt contact with a parent should be granted despite any associated risks to caregiver or child, as long as supervision is sought (table 1). Alternatively, twenty-seven percent of respondents felt that if there are risks to either the child or the caregiver, no contact should be granted.

Table 1. People’s feelings towards access when danger is involved for the caregiver or child

|

|