Introduction

Would you like to be notified when a new survey report is released? Sign up here

Relationships Australia has been strongly advocating for increased awareness of the benefits of social connection and the risks of poor mental and physical health associated with social disconnection. One factor that has not received as much attention is the effect of neighbour disputes in damaging social capital and reducing community connectedness.

Many community legal centres and local governments are reporting increases in the number of neighbour disputes over the past few years. Increasingly, conflict between neighbours has been associated with increasing housing density as the Australian population grows, particularly in expanding major cities[1]

In 2012, the South Australian Legal Services Commission reported neighbour disputes as the primary reason people sought information from the Commission, with more than half of neighbourhood disputes involving conflict about fences, encroachments and retaining walls. Each year, thousands of noise complaints are also reported to local councils, police and state mediation authorities (Kemp, 2012).

People who are negatively affected by a neighbour have three main avenues open to them to resolve the issue. Many services advise the best course of action is to try to resolve the issue through a personal approach such as talking with your neighbour and sorting it out in a friendly and informal way. If the problem remains unresolved, you may have an option for formal mediation or legal avenues. Many regulatory bodies are also turning to alternative dispute resolution models to providing a more cost-effective, faster approach that limit negative impacts on neighbour relationships.

Relationships Australia’s March 2019 online survey sought to discover whether visitors to our website have experienced conflict with their neighbours and understand common avenues used to resolve disputes.

[1] For example, see www.qld.gov.au/law/housing-and-neighbours/disputes-about-fences-trees-and-buildings, and City of Sydney (2013)

Previous research finds that…

- In 2010, over 10% of Australians living in privately owned dwellings had some experience in dealing with noisy neighbours (ABS, 2012).

- 7000 of 20,000 calls for advice to the Dispute Settlement Centre of Victoria related to fences.

- Common causes of conflict over noise include problems with barking dogs, musical instruments, parties, construction, alarms, garden machinery and power tools (The City of Sydney, 2013).

Results

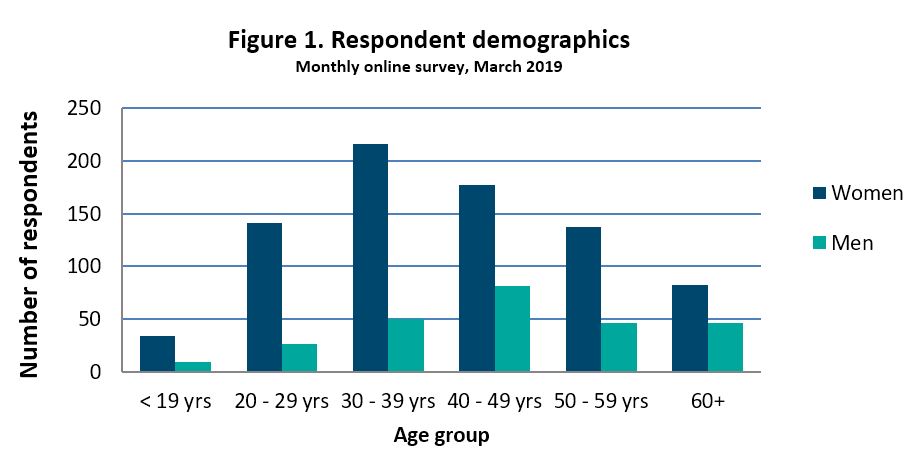

More than 1,150 people responded to the Relationships Australia online survey in March 2017. Three-quarters of survey respondents (75%) identified as female, with more females than males responding in every age group (see Figure 1 below). Just under eighty-five per cent of survey respondents were aged between 20‑59 years, and more than 50 per cent of respondents comprised women aged between 20‑49 years (inclusive).

As for previous surveys, the demographic profile of survey respondents remains consistent with our experience of the groups of people that would be accessing the Relationships Australia website.

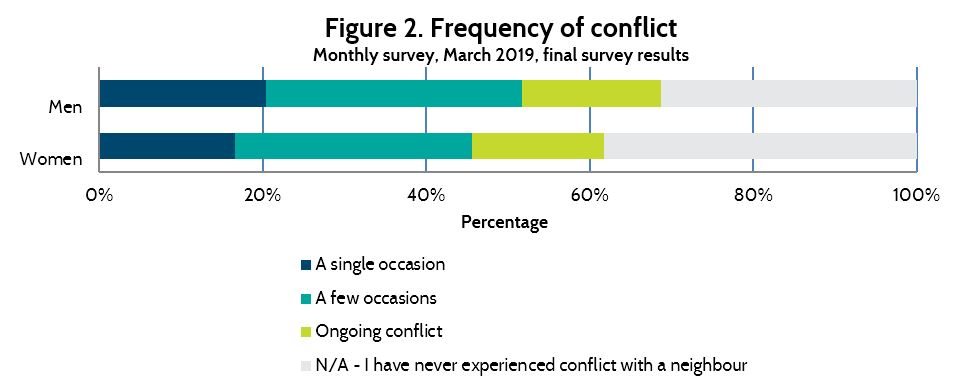

More than 60 per cent of women and 68 per cent of men reported they had experienced conflict with neighbours. There were significant differences in the reports of men and women when they were asked about the frequency of conflict with neighbours. Men (21%) were more likely than women (17%) to report the conflict was a one-off experience, while around 17% of men and women reported the conflict with their neighbour(s) was ongoing (figure 2).

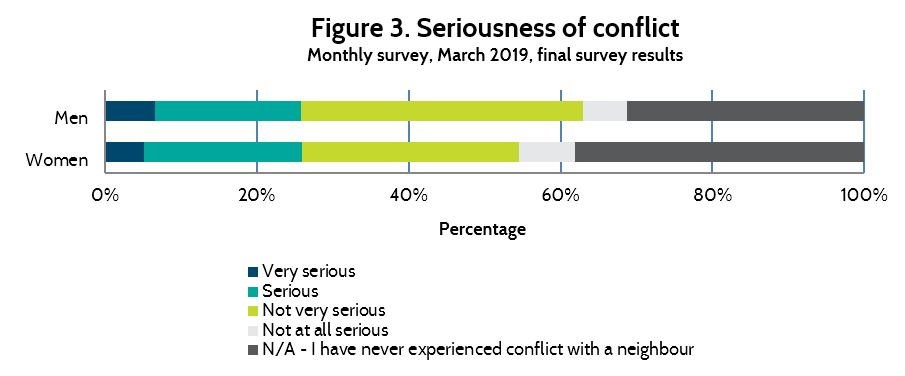

Just under half of male survey respondents (43%) and female survey respondents (41%) reported that the conflict with their neighbour was not very serious or not serious at all. In contrast, more than one-quarter (26%) of survey respondents reported the conflict with their neighbours was very serious or serious (figure 3).

The most common methods for responding to conflict with neighbours reported by survey respondents was to try to resolve the issue by talking to the person (37%), or by ignoring it (12%). Anonymous notes and moving house were the least likely methods reported for responding to conflict (table 1).

Table 1. Reports of responses to conflict with neighbours by gender

|

Response to conflict |

Women

|

Men

|

|

I ignored it |

11 |

16 |

|

I tried to resolve the issue by leaving an anonymous note/s |

|

|

|

I tried to resolve the issue by communicating with the person in writing |

|

|

|

I tried to resolve the issue by talking to the person |

37 |

38 |

|

I tried to resolve the issue with the help of a third party, such as a mediator, local council or community service |

|

|

|

I tried to resolve the issue by approaching the police or court |

|

|

|

I moved to another home |

|

|

Fewer than half of survey respondents were satisfied with the outcome, regardless of which response to the conflict they had undertaken (table 2).

Table 2. Reports of responses to conflict with neighbours by satisfaction with outcome

|

Response to conflict with a neighbour

|

Satisfaction with outcome |

||

|

Yes

|

No

|

Unsure

|

|

|

I ignored it |

46 |

28 |

26 |

|

I tried to resolve the issue by leaving an anonymous note/s |

47 |

40 |

13 |

|

I tried to resolve the issue by communicating with the person in writing |

44 |

35 |

21 |

|

I tried to resolve the issue by talking to the person |

43 |

40 |

17 |

|

I tried to resolve the issue with the help of a third party, such as a mediator, local council or community service |

38 |

45 |

11 |

|

I tried to resolve the issue by approaching the police or court |

33 |

46 |

21 |