Introduction

Would you like to be notified when a new survey report is released? Sign up here

Parenting and bringing up children is a complex process of supporting and promoting emotional, physical, social and intellectual development. The skills children develop from a very young age help the child to flourish later in life. These skills are supported by effective parenting and therefore as a parent, you play a very significant role in their life.

Consensus on effective parenting shifts and changes with the times. Despite this, there is agreement on the benefits of consistency, routines, boundaries, choices, honesty and fairness in one’s parenting. However, children are individuals. What works for one child may not work for another. As such, much research is conducted on best parenting practices.

One topic which dominates the family research field is the concept of discipline. It is understood that inconsistent discipline in preschool-aged children can be a risk factor for adverse development (ARACY, 2015). Conversely, providing social connections, being a nurturing parent and encouraging cognitive stimulation are all understood as protective factors, which buffers the influence of risk factors (ARACY, 2015).

Parenting older children provides different opportunities for engagement. AIFS found that most adolescents seek help for their everyday personal and emotional problems from their parents and friends, rather than from health professionals (Gray & Daraganova 2017). As such, understanding how to respond to adolescents who are seeking help is important in establishing appropriate pathways of care.

The August-September survey sought to explore people’s experiences of parenting, looking at the concepts of emotional support, discipline and support in children’s interests.

Previous research finds that…

- Mental disorders in children are more common in families facing other challenges such as unemployment and or family breakup (Young Minds Matter Survey, 2014).

- Two-thirds of adolescents diagnosed with major depressive disorder (based on their self-reported information) said that their parents knew ‘little’ or ‘not at all’ about how they were feeling (Young Minds Matter Survey, 2014).

- A survey conducted in Victoria found that ninety-one percent of parents had confidence in their parenting ability (Parenting Research Centre, 2017). However, twenty-eight percent felt they were too critical of their children.

- Seventy-nine percent of parents of adolescents used the internet for parenting information (Parenting Research Centre, 2017).

Results

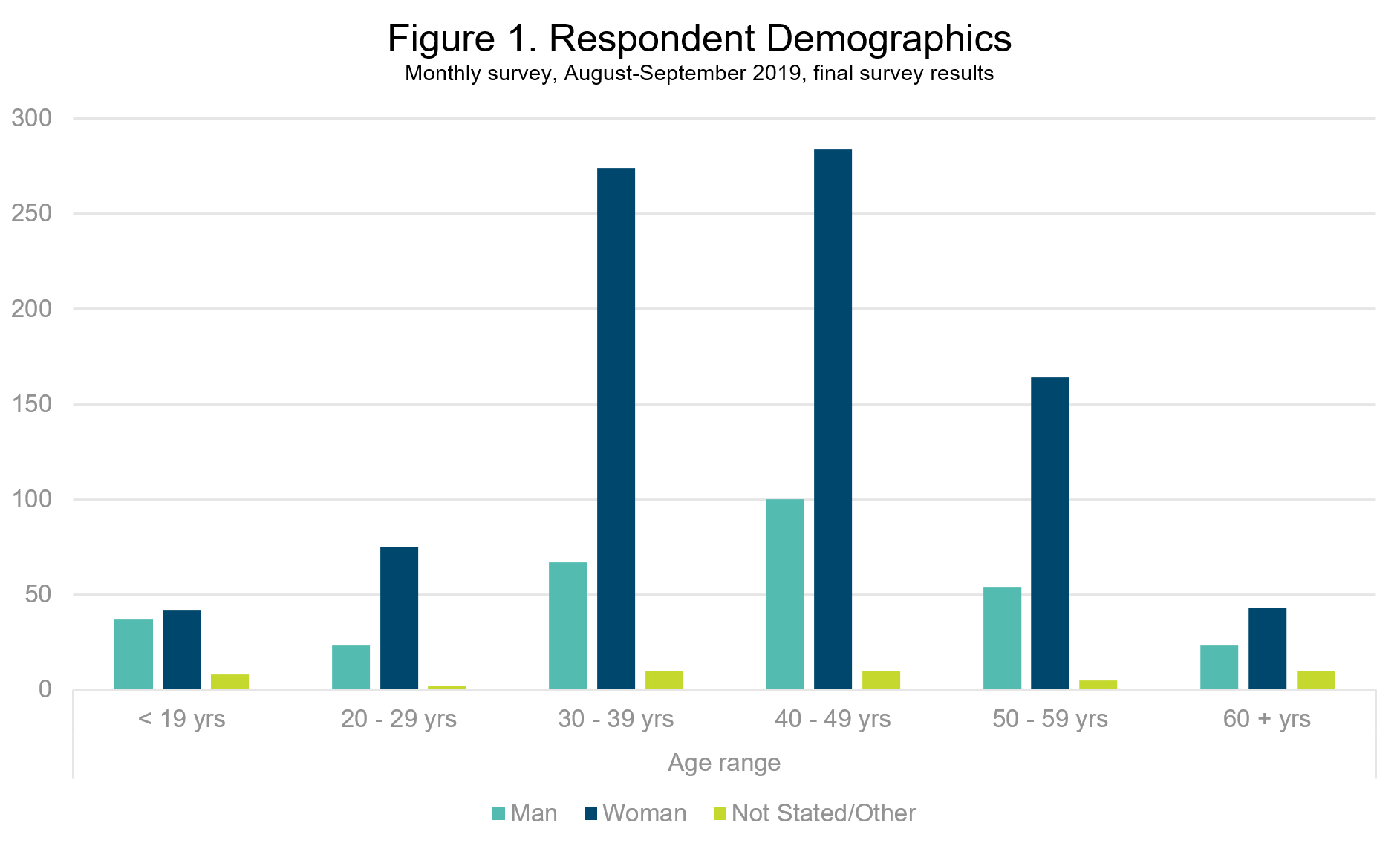

1250 people responded to the August/September survey on parenting on the Relationships Australia website. Seventy-one percent of respondents identified as women, twenty-five percent were men and a further four percent did not state their gender or chose ‘other’ (figure 1). As with past surveys, the majority of respondents were aged 30-49 years (60%). The demographic profile of survey respondents remains consistent with our experience of the groups of people that would be accessing the Relationships Australia website.

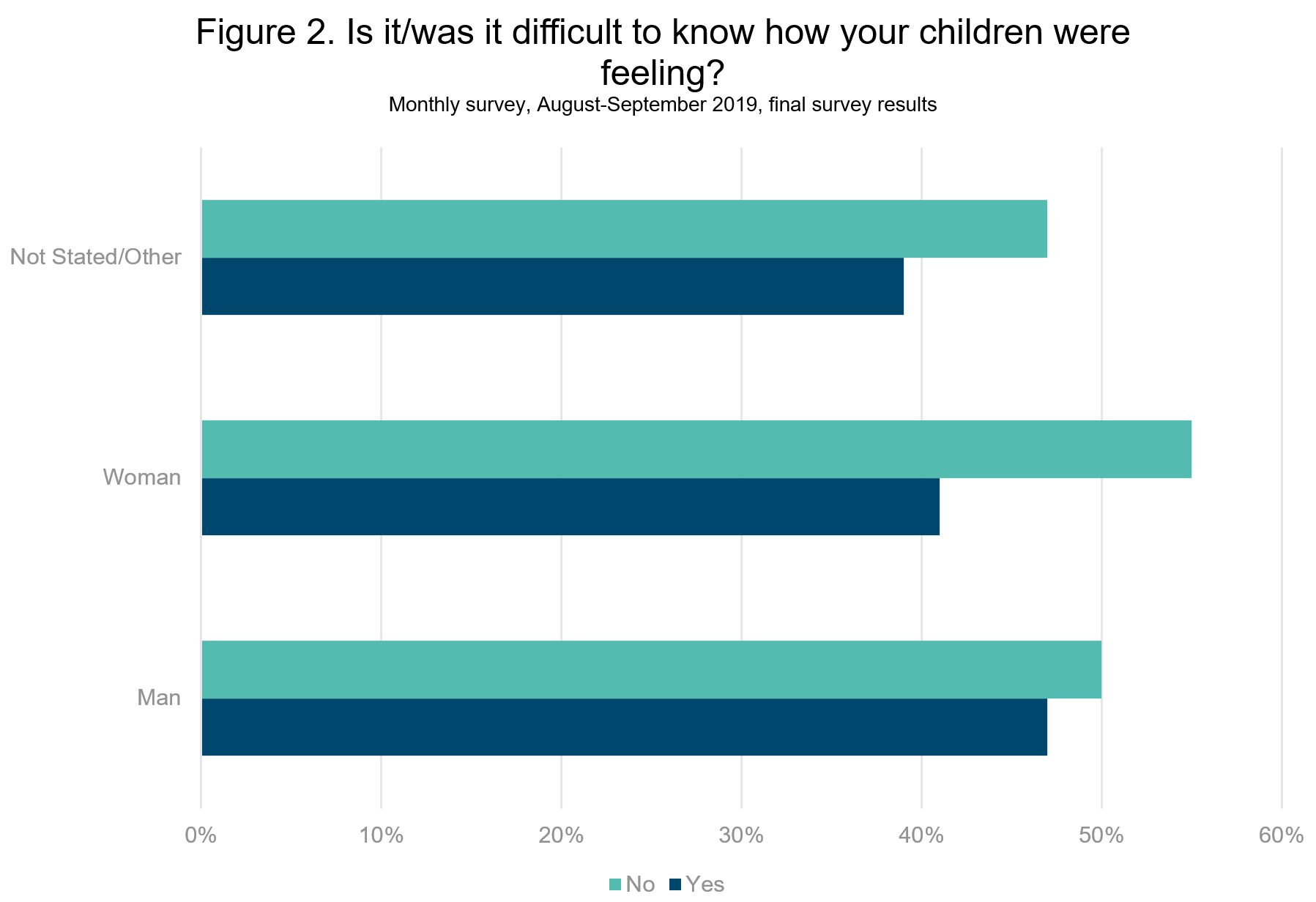

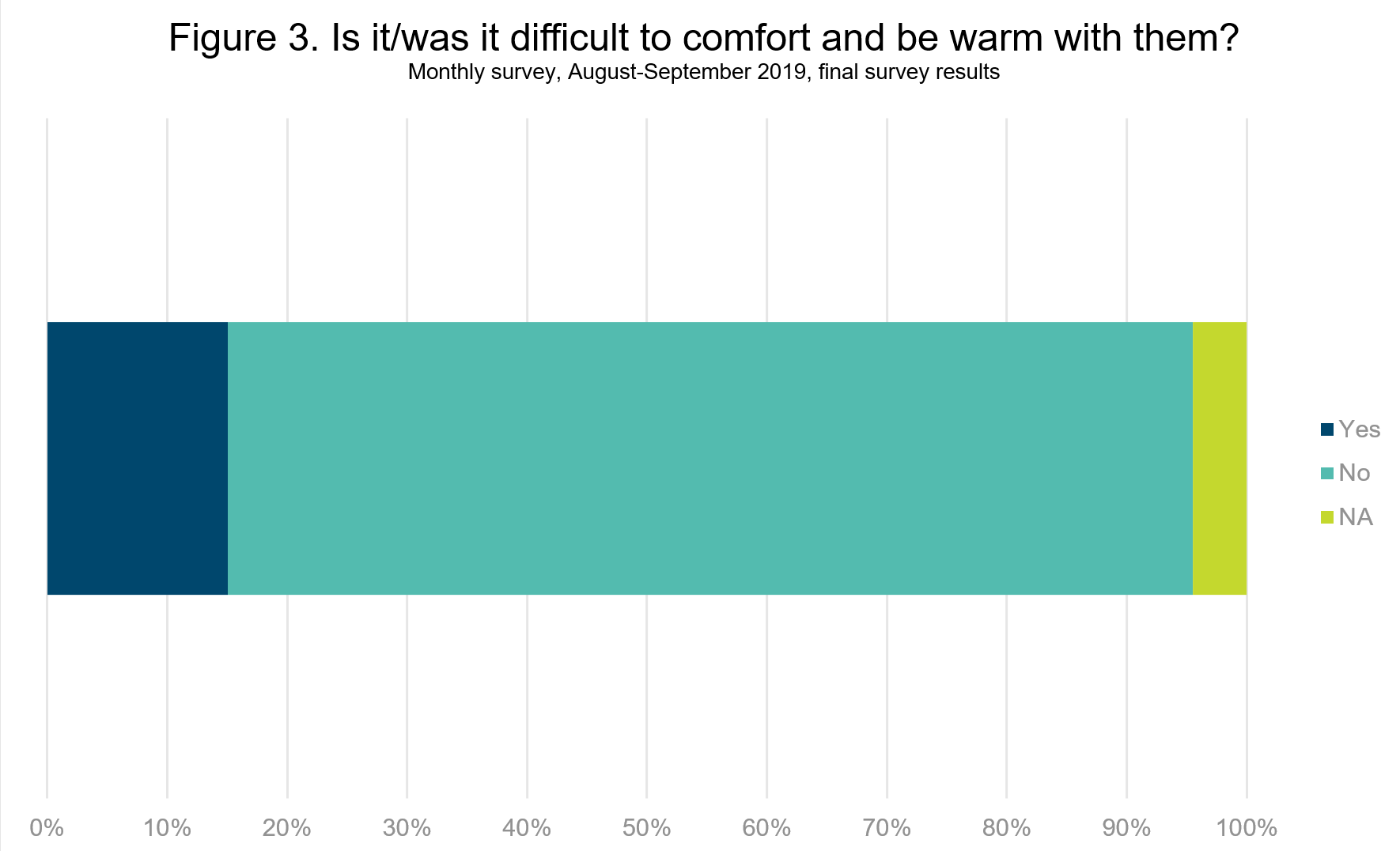

This month’s survey found that a slight majority (53%) of parents had difficulty knowing how their child was feeling (figure 2). There was a weak correlation between these variables, suggesting that despite gendered understandings of emotional intelligence, a parent’s gender has little effect on their ability to know how their child is feeling. Despite some apparent difficulty understanding feelings, a strong majority (80%) felt comfortable comforting and being warm with their children (figure 3). This suggests that even if parents have difficulty understanding exactly how their child is feeling, they can provide a warm and comfortable presence.

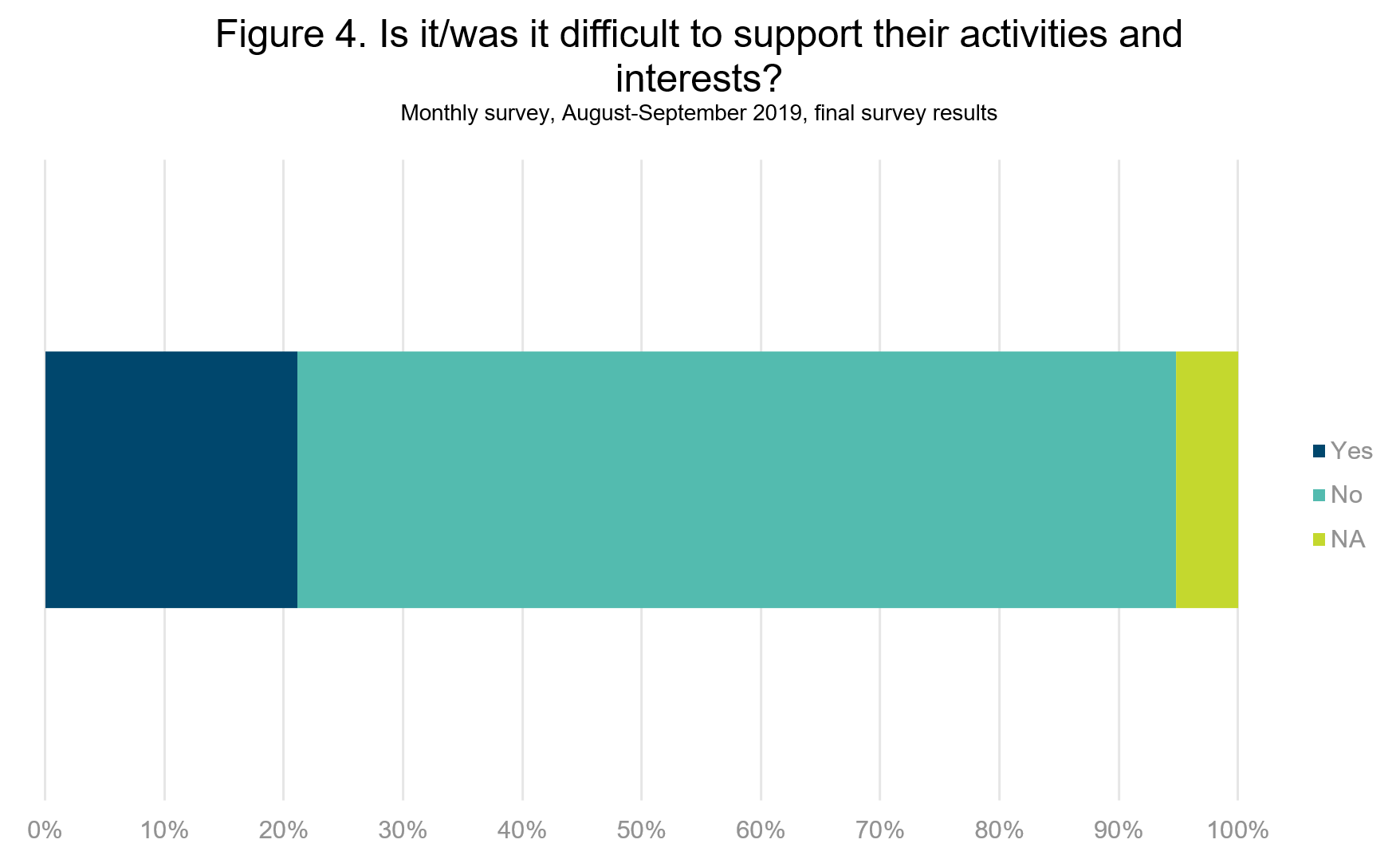

Similarly, most (73%) found is easy to support the activities and interests of their child (figure 4). Across several questions, sixty-six percent of parents felt capable of providing support and comfort to their children (figures 3 & 4). Similarly, only seven percent found it difficult to either comfort their child or support them in their interests. Together, these results suggest that most respondents feel capable of providing support and comfort, however many respondents struggle with interpreting their child’s feelings.

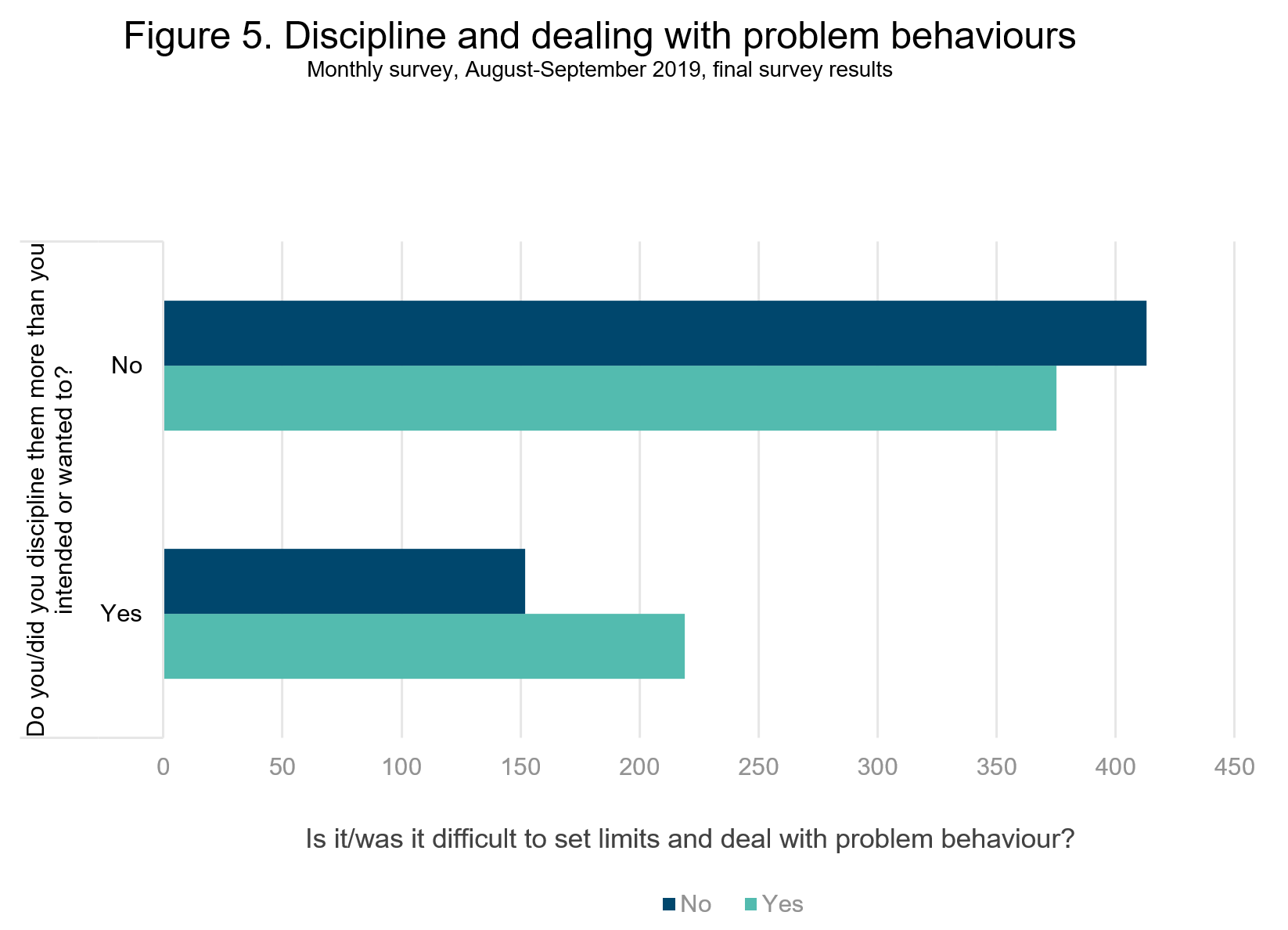

When it came to disciplining problem behaviour, many parents found it difficult to set limits and discipline effectively (49%) (figure 5). Despite the majority (51%) of respondents suggesting they had no difficulty dealing with problem behaviour, thirty percent of these respondents felt they had to discipline their children more than they intended to or wanted to. This suggests that while parents are capable of disciplining their children, they sometimes feel uncomfortable doing so or wish they did not have to. Across both questions, thirty-nine percent had some difficulty with discipline (either in their feelings towards it or their ability to discipline effectively), while fifty-five percent recorded no difficulties in either circumstance.

Overall, these results suggest great things about the abilities of parents. Most feel comfortable and capable in their roles supporting, caring for and disciplining their children. Even if they do not always understand how their child is feeling, by providing boundaries, support and encouragement, they play key roles in their children’s development.

References

If you need support with parenting many organisations can offer support, information, self-help and referrals to health professionals. The following list provides the numbers to Parentline in each state and territory.

Parentline ACT

(02) 6287 3833, 9 am-5 pm Monday to Friday (except public holidays)

Parent Line NSW

1300 130 052, 9 am-9 pm Monday to Friday, 4 pm-9 pm weekends

Parentline Queensland and Northern Territory

1300 301 300, 8 am-10 pm 7 days

Parent Helpline South Australia

1300 364 100, 7.15 am-9.15 pm 7 days (calls outside these times will be redirected to the national Health Direct helpline)

Parentline Tasmania

1300 808 178, 24 hours 7 days

Parentline Victoria

132 289, 8 am-12 am 7 days

Ngala Parenting Helpline Western Australia

(08) 9368 9368 (metropolitan) or 1800 111 546 (regional callers) 8 am-8 pm 7 days

The following services may also be of interest:

- National Association for Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect: Raises public awareness of child abuse and neglect and its impacts, and develops and promotes effective prevention strategies and programs.

Visit www.napcan.org.au or call (02) 8073 3300.

- Act for Kids: Provides therapy and support services to children and families who have experienced or are at risk of child abuse and neglect.

Visit www.actforkids.com.au

- Australian Childhood Foundation: Provides a range of services to prevent child abuse. Visit www.childhood.org.au or call 1300 381 581.

- Bravehearts: A national free telephone crisis and support service for children, young people, adults and non-offending family members affected by child sexual assault.

Visit www.bravehearts.org.au or call 1800 272 831.

Resources

Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (2015). Fact Sheet 1: Risk and Protective Factors. Better Systems, Better Chances Fact Sheet Series.

Gray, S. and Daraganova, G. (2017). Chapter Seven: Adolescent help-seeking. LSAC Annual Statistical Report. [online] Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. Available at: https://growingupinaustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/publication-documents/lsac-asr-2017-chap7.pdf [Accessed 12 Dec. 2019].

Parenting Research Centre (2017). Infographic. Parenting Today in Victoria. [online] Available at: https://www.parentingrc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/PTIV-Infograp-hic_November20_FINAL.pdf [Accessed 15 Dec. 2019].

Young Minds Matter (2014). Overview. The Mental Health of Australian Children and Adolescents. [online] Available at: https://youngmindsmatter.telethonkids.org.au/siteassets/media-docs—young-minds-matter/ymmoverview.pdf [Accessed 10 Dec. 2019].