Introduction

Restorative practice offers an approach that brings together individuals, families, social networks, services and government, through informal and informal processes, to proactively build relationships to resolve or prevent conflict and wrongdoing. It can also unite theory, research and practice in diverse fields such as education, health, criminal justice, regulation, social welfare and organisational management. The fundamental premise of restorative practice is that people are happier, more cooperative and productive, and more likely to make positive changes when those in positions of authority do things with them, rather than to them or for them.

Restorative justice is a subset of restorative practice that provides an alternative to punitive responses to crime. Inspired by indigenous traditions, it brings together persons harmed with persons responsible for harm in a safe and respectful space, promoting dialogue, accountability, the building of relationships and a stronger sense of community.

In a previous survey in 2015, Relationships Australia explored restorative practice in relation to family violence. Interestingly, when asked about the importance of a range of factors to the needs of victims of family violence, respondents to the online survey were more likely to report that family and psychological support were more important to meeting the needs of victims of family violence than the perpetrator making amends for the crime or being punished, the perpetrator apologising to the victim or financial compensation.

In September 2017, Relationships Australia’s online survey sought to further understand the community’s views of restorative principles by posing a few questions to visitors to our website.

Previous research finds that…

Restorative approaches are associated with:

- improved social skills, reduced aggression and reduced exclusion of students in education settings;

- a reduction in the number of children in out of home care, number of families with a child protection plan and children at risk in social care environments;

- reductions in re-offending in youth justice across different offence types and regardless of the gender, criminal history, age or cultural background of the offenders; and

- improved health outcomes and reduced dependence on the health system.

Results

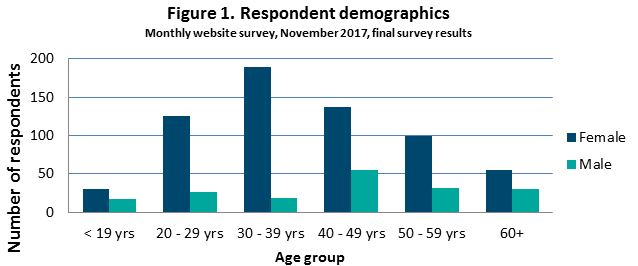

More than 850 people responded to the Relationships Australia online survey in November. Around four‑fifths of survey respondents (78%) identified as female (figure 1).

As was the case for last month’s survey, more females than males responded in every age group (figure 1). More than eighty-five per cent (87%) of survey respondents were aged between 20‑59 years, with the highest number of responses collected for women aged between 30-39 years (inclusive).

The demographic profile of survey respondents remains consistent with our experience of the people that would be accessing the Relationships Australia website.

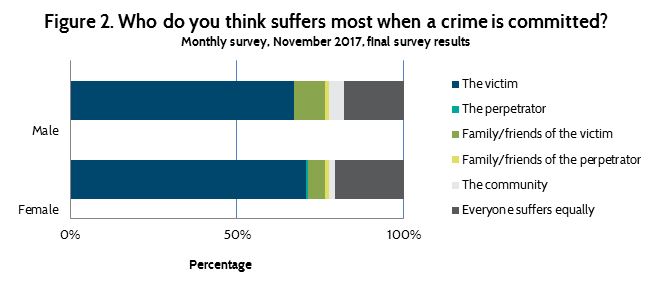

Survey respondents were asked their views on six principles that are associated with restorative justice. A significant majority of male and female survey respondents thought that the victim suffered most when a crime was committed (70%), followed by the family and friends of the perpetrator (20%) and the family and friends of the victim (6%). Almost no survey respondents considered that the perpetrator suffered the most when a crime is committed (see figure 2).

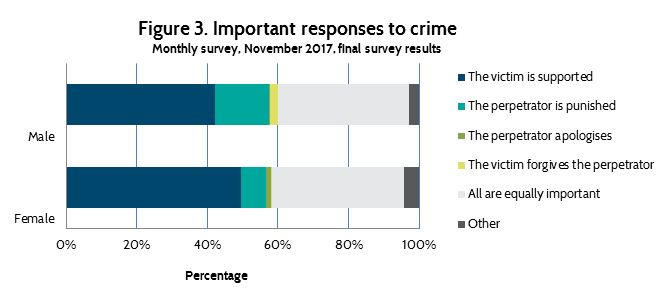

Both male and female survey respondents reported that victim support was the most important response to crime (48%). Men (15%) were more likely than women (7%) to report that punishment was an important response to crime (see figure 3).

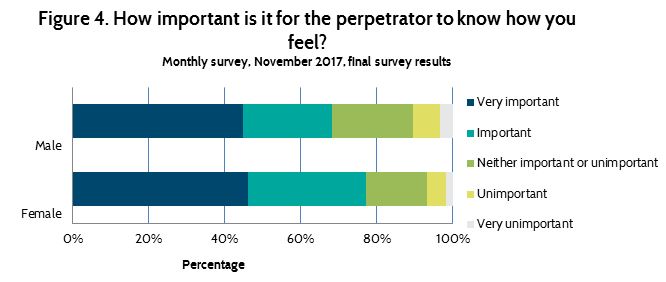

Survey respondents placed high importance on the perpetrator knowing how they felt if a crime was committed against them. Women (77%) were more likely than men (68%) to report that it was very important or important that the perpetrator knows how they feel when a crime was committed against them (see figure 4).

Just under half of survey respondents (46%) reported that it was important for them to have an opportunity to meet face to face with the perpetrator if a crime was committed against them. A further 42 per cent of women and men thought that it was neither important nor unimportant.

Three‑quarters of women (76%) and men (71%) reported that prison was not the most appropriate way to punish criminals, regardless of what crime they committed, with just under 70 per cent of survey respondents disagreeing that prison was rehabilitative.

References

Braithwaite, John (2004). Restorative Justice and De-Professionalization. The Good Society 13 (1): 28–31.

Daly, K & Hayes, H (2001). Restorative justice and conferencing in Australia Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice no 186, Australian Institute of Criminology.

Mason, P, Ferguson, H, Morris, K, Munton, T & Sen, R. (2017) Leeds Family Valued Evaluation report

O’Brien, K, Welsh, D, Barnable, A (2016).The Impact of Introducing Restorative Care on Client Outcomes and Health System Effectiveness in in an Integrated Health Authority, Home Health Care Management & Practice, 29( 1): 13-19.

Pennell, J. & Burford, G. (1994). Widening the circle: The family group decision making project. Journal of Child & Youth Care , 9: 1-12.

Liebmann, M. Restorative Justice: How it Works, 2007, London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.