Introduction

Would you like to be notified when a new survey report is released? Sign up here

Many people feel that a workplace Christmas party is an excellent way to encourage staff bonding among those who may not usually interact. Eventbrite surveyed over 1000 employers and employees in 2017 and found that eighty-five percent of employers believe that Christmas parties have a positive impact on staff morale and keep the team motivated (Eventbrite, 2017). Similarly, workplace friendships are shown to be great for improving organisational outcomes like efficiency and performance (Berman et al., 2002; Song, 2006). However, workplace friendships also contribute to a larger project of social and personal wellbeing (Rumens, 2016; Pedersen et al. 2012; Andrew & Montague, 1998).

Despite this, workplace Christmas parties are notorious for encouraging bad behaviour and have the potential to damage future working relationships. Pre-Christmas celebrations often involve alcoholic beverages. As such, something which may usually seem out of place in the office environment may become commonplace and acceptable. The accompanying behaviour, brought about through a combination of alcohol and excited, end-of-year spirits, can lead to a breakdown in workplace relationships (Erikkson et al. 2008).

Another pervasive idea behind the work Christmas event is that it represents a celebration and recognition by employers of the hard work of their employees. It is thought that this reward will, in turn, encourage greater workplace engagement in the future. However, studies have found little correlation between workplace engagement and workplace rewards (Kulikowski & Sedlak, 2017).

Previous research finds that…

- A 2017 survey conducted by Eventbrite found that, on average, Australian workplace spend $9722 on their work Christmas party. Four percent of Australian businesses will spend more than $100,000 on their Christmas party (Eventbrite, 2017).

- The same survey found that thirty-five percent of employees would be attending a Christmas party, twenty-seven a lunch, twenty percent a cocktail party, twenty-six percent a sit-down dinner and seven percent an activity or experiential party (Eventbrite, 2017).

- Eventbrite found that forty-eight percent of Australian employers will invite employees partners to the pre-Christmas gathering, while thirty-six percent will invite their customers (2017).

- A survey conducted by the Tourism and Transport Forum Australia found that 70% of respondents thought the boss should cover the cost of the work Christmas party (TTF 2015). Among those, twenty-two percent also thought the boss should also be covering the transport home for the attendees.

- A survey conducted by InstantPrint, a UK company, found that those who work in Human Resources departments spend most on their Christmas party outfits – £181.61 (or 349.68 AUD). Additionally, they found that fifty-one percent of Human Resources employees were nervous about attending work the day following the party (InstantPrint 2017).

These findings suggest that workplace Christmas parties can be a positive influence on workplace comradery and morale, while others feel that these celebrations can put a strain on employee’s budgets and working relationships.

Relationships Australia conducted a survey this festive season to understand how our website users view pre-Christmas get-togethers and to understand more about how they affect our working relationships.

Results

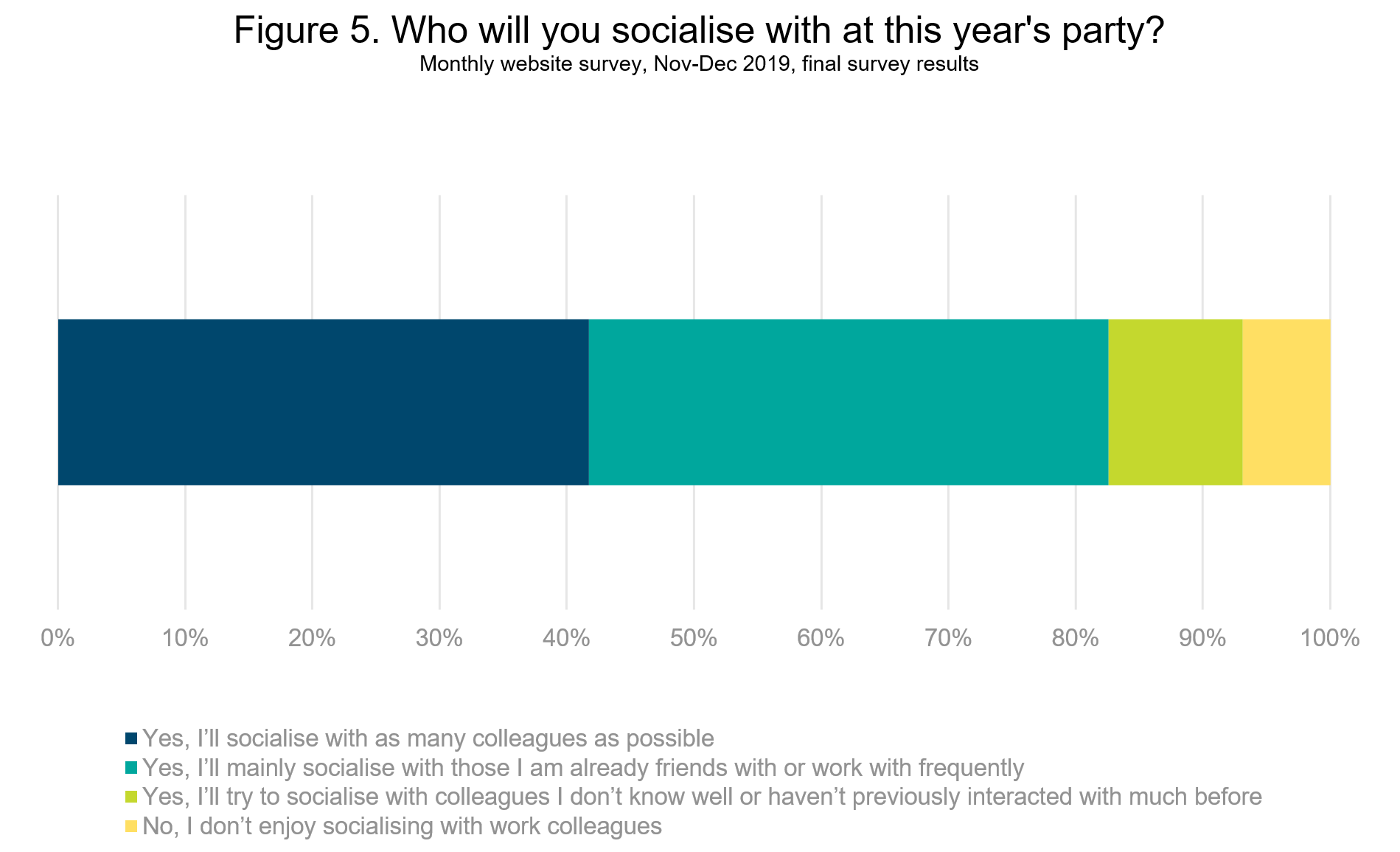

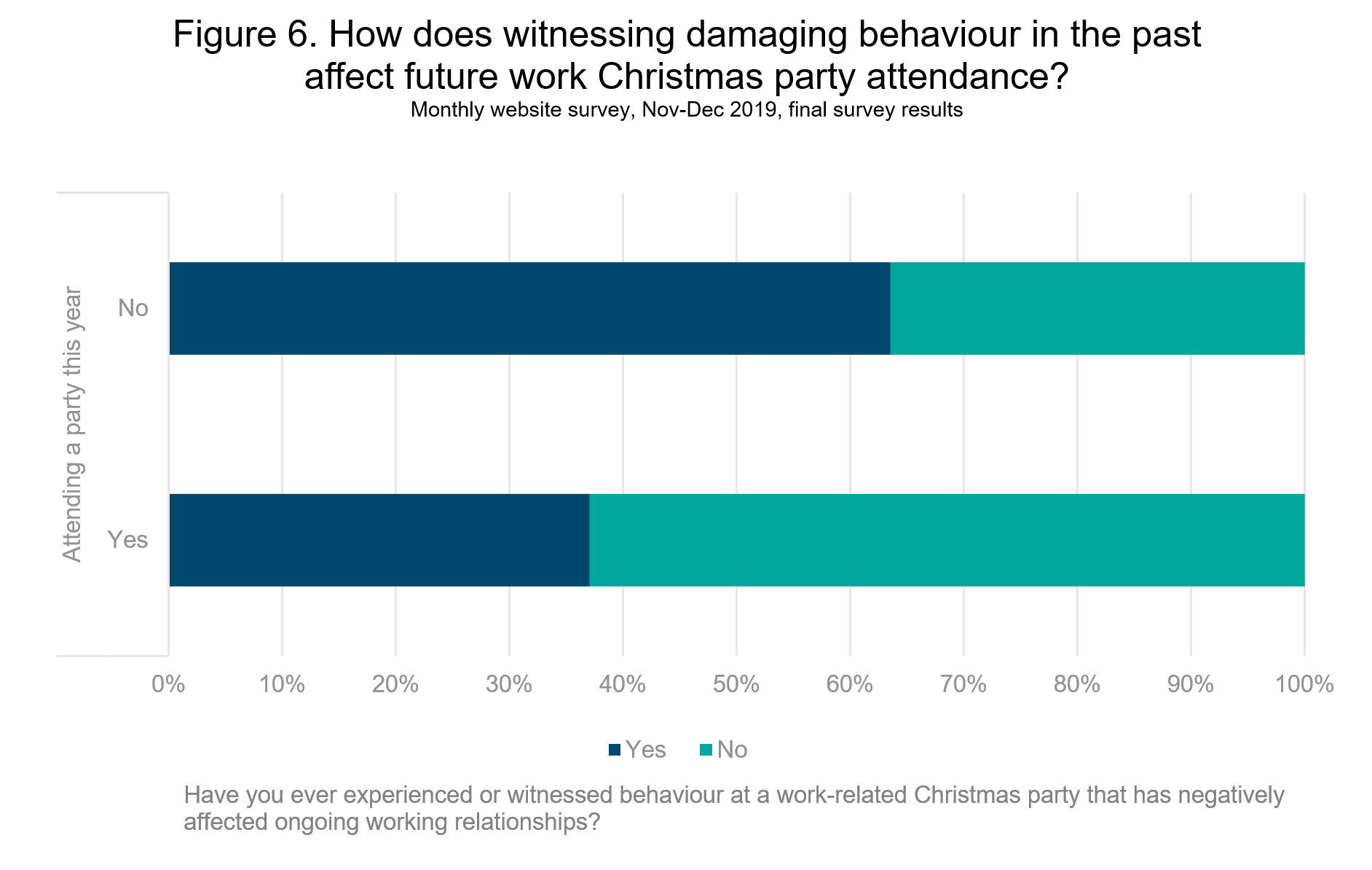

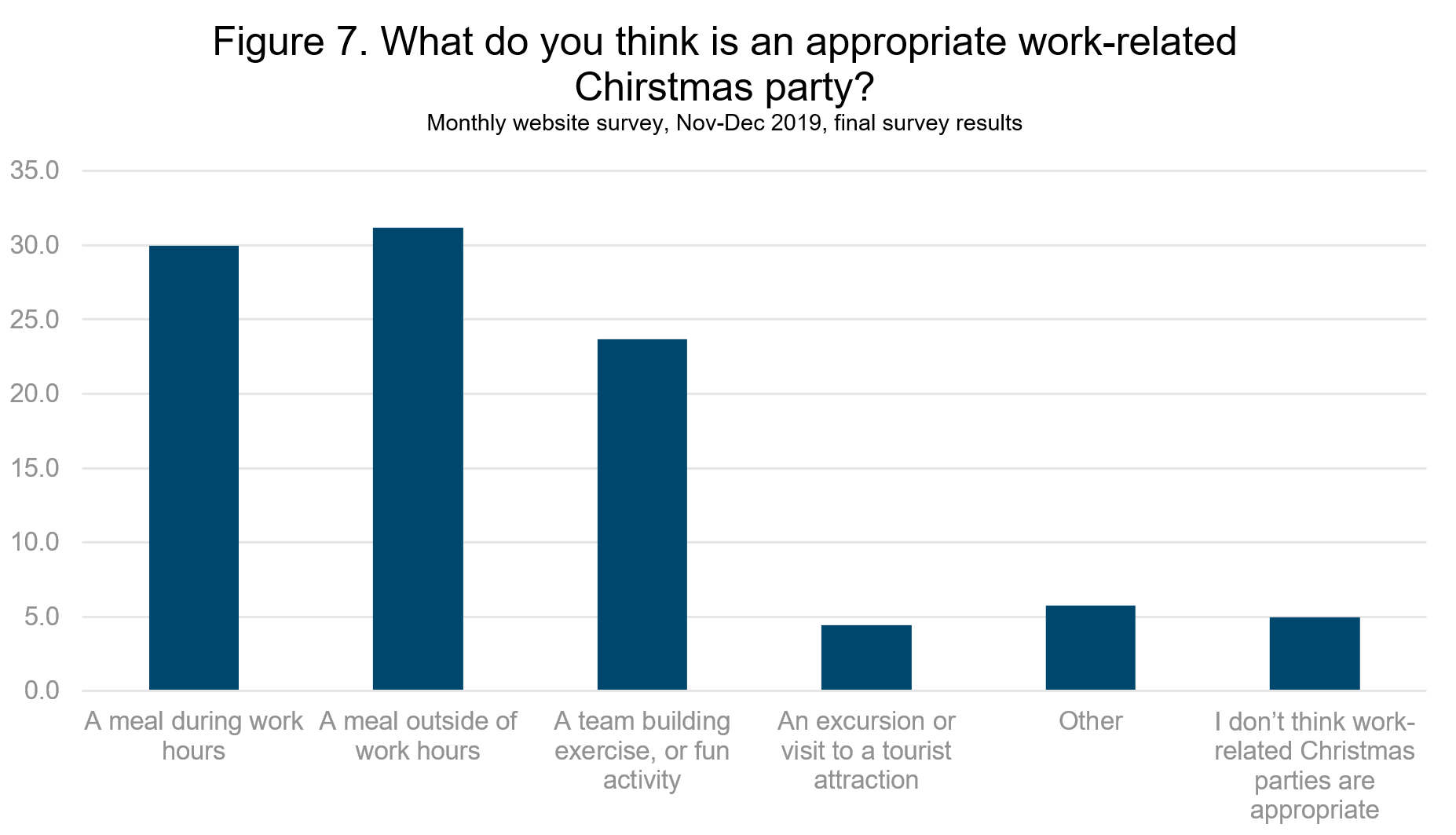

748 people responded to the Relationships Australia November-December 2019 survey. Seventy-one percent of respondents were women, twenty-six percent were men and three percent did not state their gender or chose ‘other’ (figure 1). As for previous surveys, the demographic profile of survey respondents is consistent with our experience of the groups of people that would be accessing the Relationships Australia website.Figure 2 illustrates that fifty-nine percent of the respondents will be attending/or have attended a work-related Christmas party this year. A further thirty-five percent said they would not attend and six percent were not sure at the time they completed the survey.We found that for the majority (39%) of respondents attending a work Christmas party this year, it would be their bosses shout (figure 3). A further seventeen percent would be paying for the party themselves, while the other twelve percent were sharing the costs with their employers.Despite a widespread belief that a Christmas party is an excellent way to reward employees for their hard work throughout the year, forty percent of respondents felt a bonus was the best reward (figure 4). Twenty-two percent felt that a Christmas party paid for in full by their employer was the best reward. This was especially popular among respondents who are footing the bill for this year’s Christmas party (22%).Another common conception is that work-place Christmas parties encourage mingling among staff who may not usually meet. Figure 5 illustrates that a fraction of a majority (42%) support this assumption and will try to socialise with as many colleagues as possible. Forty-one percent will mostly socialise with people they are already friends with or work closely with. Eleven percent will take the opportunity to expand their social horizons and try to meet colleagues that they have had little to do with previously. Finally, seven percent, while still planning on attending the party, do not enjoy socialising with their colleagues, friends or foes.Work Christmas parties have the potential for encouraging poor behaviour which affects future attendance. While a majority (53%) of respondents had not witnessed any poor behaviour at a work-related Christmas, those who had (38%) appeared less likely to attend a Christmas party this year than those who had not (figure 6).Given these statistics, many people (31%) still felt that a meal outside of work hours was appropriate. A similar number (30%) felt a meal during work hours was more suitable, while another twenty-four percent felt a team-building exercise or fun activity was a good alternative. A small proportion (5%) felt that work-related Christmas parties were inappropriate, of these respondents, forty-one percent had witnessed or been involved in damaging behaviour at previous parties.

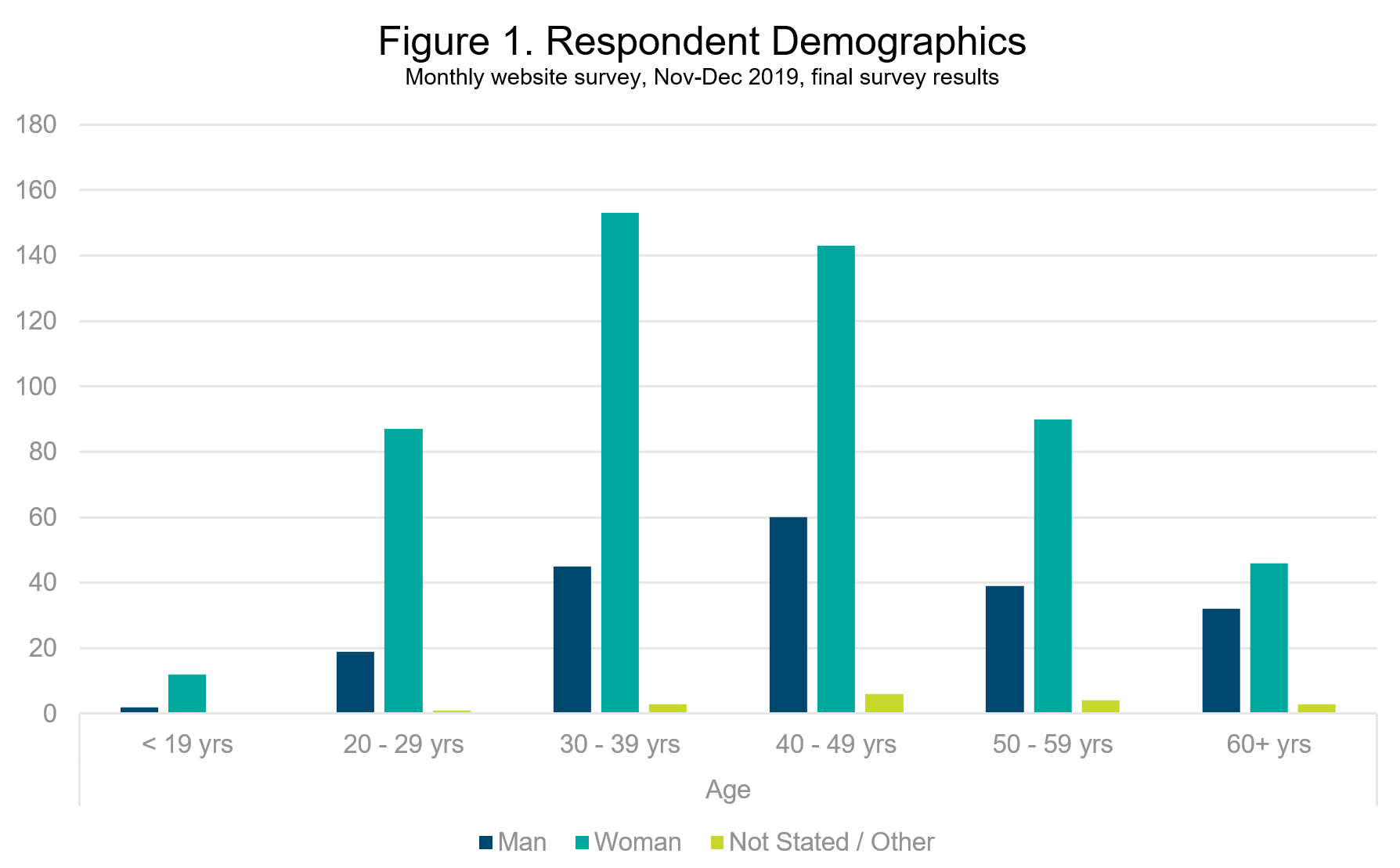

748 people responded to the Relationships Australia November-December 2019 survey. Seventy-one percent of respondents were women, twenty-six percent were men and three percent did not state their gender or chose ‘other’ (figure 1).

748 people responded to the Relationships Australia November-December 2019 survey. Seventy-one percent of respondents were women, twenty-six percent were men and three percent did not state their gender or chose ‘other’ (figure 1).

As for previous surveys, the demographic profile of survey respondents is consistent with our experience of the groups of people that would be accessing the Relationships Australia website.

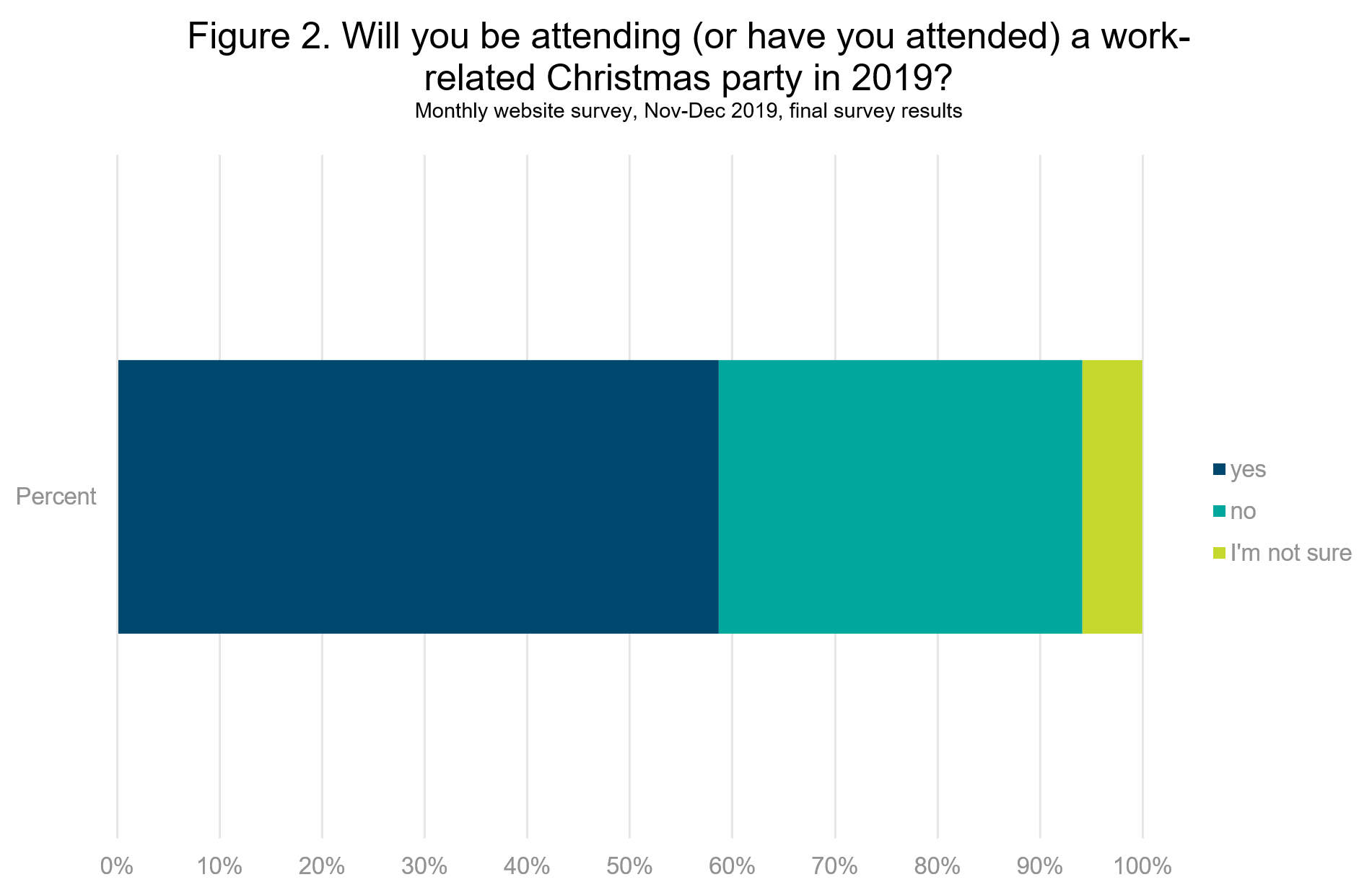

Figure 2 illustrates that fifty-nine percent of the respondents will be attending/or have attended a work-related Christmas party this year. A further thirty-five percent said they would not attend and six percent were not sure at the time they completed the survey.

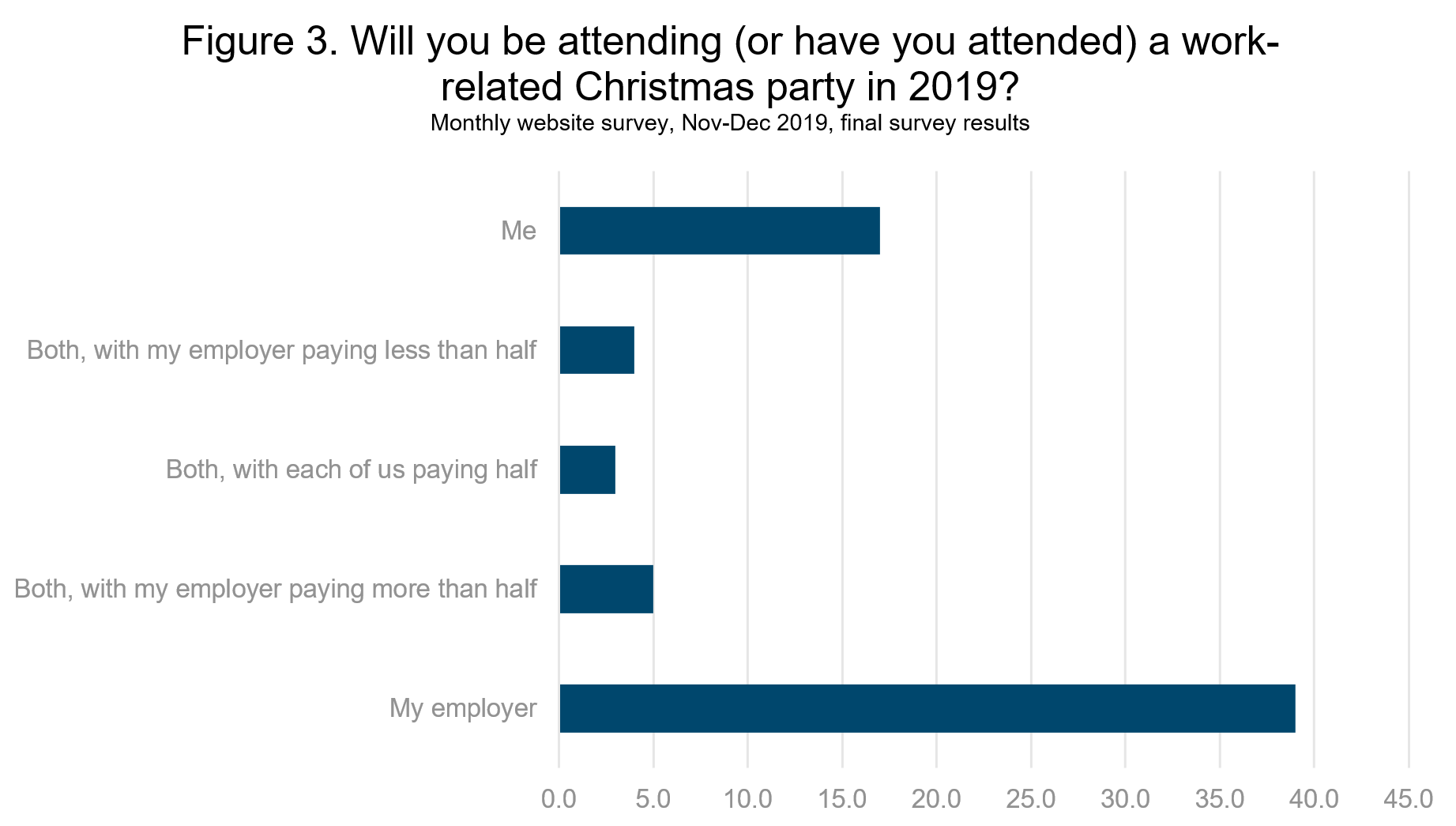

We found that for the majority (39%) of respondents attending a work Christmas party this year, it would be their bosses shout (figure 3). A further seventeen percent would be paying for the party themselves, while the other twelve percent were sharing the costs with their employers.

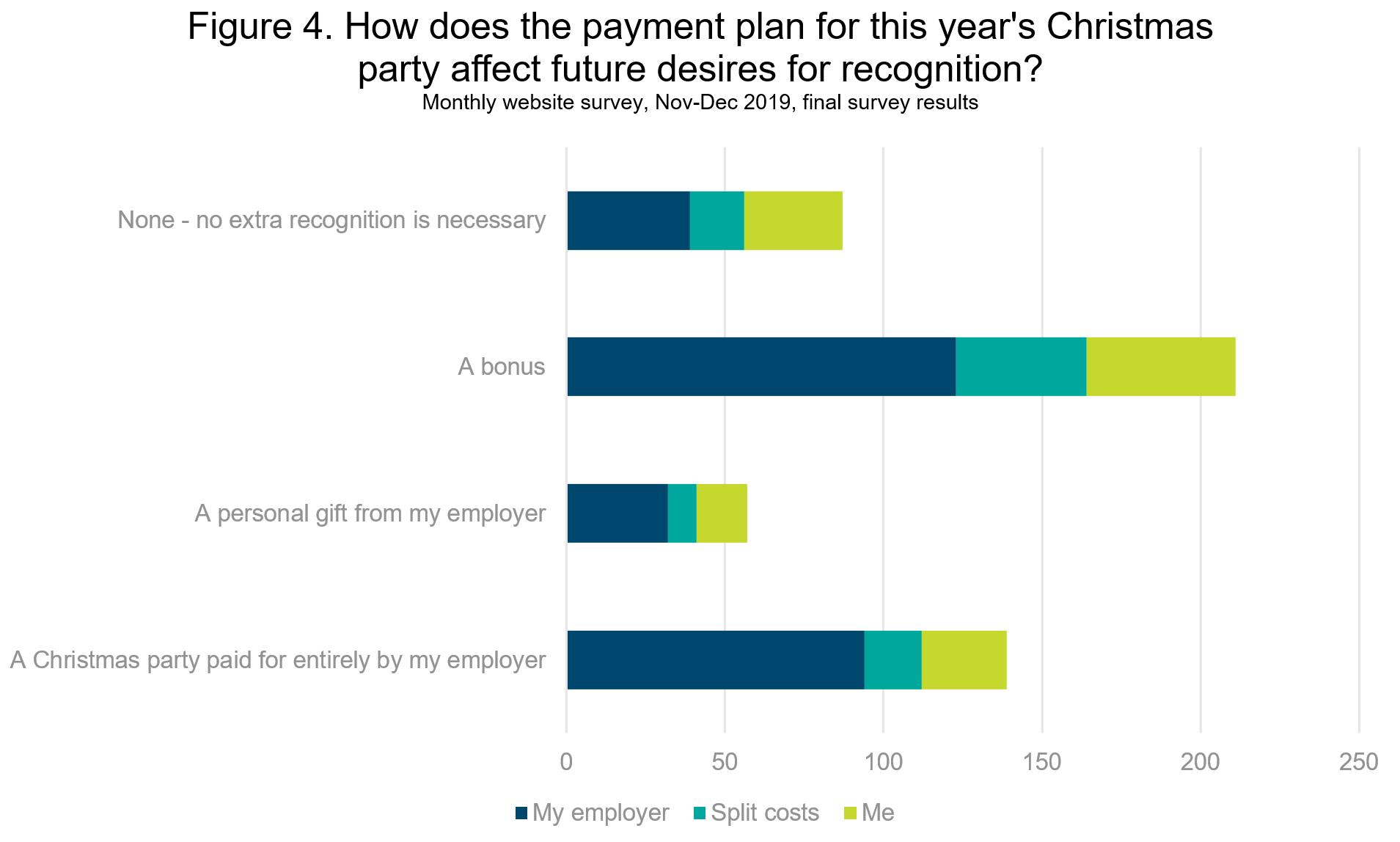

Despite a widespread belief that a Christmas party is an excellent way to reward employees for their hard work throughout the year, forty percent of respondents felt a bonus was the best reward (figure 4). Twenty-two percent felt that a Christmas party paid for in full by their employer was the best reward. This was especially popular among respondents who are footing the bill for this year’s Christmas party (22%).

Another common conception is that work-place Christmas parties encourage mingling among staff who may not usually meet. Figure 5 illustrates that a fraction of a majority (42%) support this assumption and will try to socialise with as many colleagues as possible. Forty-one percent will mostly socialise with people they are already friends with or work closely with. Eleven percent will take the opportunity to expand their social horizons and try to meet colleagues that they have had little to do with previously. Finally, seven percent, while still planning on attending the party, do not enjoy socialising with their colleagues, friends or foes.

Work Christmas parties have the potential for encouraging poor behaviour which affects future attendance. While a majority (53%) of respondents had not witnessed any poor behaviour at a work-related Christmas, those who had (38%) appeared less likely to attend a Christmas party this year than those who had not (figure 6).

Given these statistics, many people (31%) still felt that a meal outside of work hours was appropriate. A similar number (30%) felt a meal during work hours was more suitable, while another twenty-four percent felt a team-building exercise or fun activity was a good alternative. A small proportion (5%) felt that work-related Christmas parties were inappropriate, of these respondents, forty-one percent had witnessed or been involved in damaging behaviour at previous parties.

References

Andrew, A., & Montague, J. (1998). Women’s friendship at work. Women’s Studies International Forum, 21(4), 355-361.

Berman, E. M., West, J. P., & Richter, M. N., Jr. (2002). Workplace relations: Friendship patterns and consequences (according to managers). Public Administration Review, 62(2), 217–230.

Eventbrite. (2017). Eventbrite Aussie Workplace Christmas Party Index – 2017. Retrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/EventbriteAU/eventbrite-aussie-workplace-christmas-party-index-2017

InstantPrint UK. (2017). Office Workers Reveal Their Christmas Party Antics – Does Yours Match Up?. Retrieved from https://www.instantprint.co.uk/printspiration/be-inspired/office-workers-reveal-their-christmas-party-antics

Kulikowski, K., & Sedlak, P. (2017). Can you buy work engagement? The relationship between pay, fringe benefits, financial bonuses and work engagement. Current Psychology, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9768-4.

Rumens, N. (2016). Researching workplace friendships. Journal of Social And Personal Relationships, 34(8), 1149-1167.

Pedersen, V. B., Lewis, S. (2012). Flexible friends? Flexible working time arrangements, blurred work-life boundaries and friendship. Work, Employment & Society, 26, 464–480.

Song, S. H. (2006). Workplace friendship and employee’s productivity: LMX Theory and the case of the Seoul City Government. International Review of Public Administration, 11, 47–58.

Tourism and Transport Forum Australia. (2015). Survey: Boss will pay for work Christmas party but receive no gift. Retrieved from https://www.ttf.org.au/survey-boss-will-pay-for-work-christmas-party-but-receive-no-gift/